By Rebecca Grapevine

Federal law requires states to update their plans for improving Medicaid health care quality at least every three years.

Georgia, however, published its most recent quality plan in February 2016. It’s at least two years out of date.

The guidelines aim to ensure members in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (known as PeachCare in Georgia) get quality health care and state taxpayers get a good return on their investment.

“With the large state investment in Medicaid, the state should have the information it needs to hold the contracted organizations accountable and ensure they are best serving the needs of enrollees,” said Laura Harker, senior policy analyst at Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

Medicaid and PeachCare provide health insurance to about 2 million low-income and disabled Georgians, most of them children. Georgia, like most other states, contracts with private insurance companies to provide health care services for most Medicaid members and all 150,000 or so PeachCare kids. In Georgia, these contractors are called Care Management Organizations (CMOs).

The four CMOs in Georgia — Amerigroup, CareSource, Peach State, and WellCare — are paid a total of about $4 billion annually for these services.

Sarah Somers, a managing attorney at the National Health Law Program, pointed out that the state pays each CMO a set amount for each patient’s care. If the companies do not spend all of that on patient care, they keep the money, as in most other state Medicaid systems, she said. “Without information about how they’re delivering care, how well they’re doing it, you’re not being a good steward of taxpayer money,” Somers added.

“You’re just paying out that money without the public having any ability to see how well it’s spent” if quality measures are missing or late, said Somers. Three of the four state CMOs are owned by publicly traded Fortune 100 companies.

Georgia’s 2016 quality strategy report detailed a range of Medicaid rules, such as:

** How many doctors, dentists, and mental health professionals that CMO networks must provide in a given geographic range;

** Acceptable wait times to see a health provider;

** Plans for addressing health disparities;

** Quality reporting guidelines for the CMOs;

** Standards and sanctions for the CMOs.

The 2016 Georgia report said the state would publish a new quality strategy in 2020. It is now February 2021 — and no new plan is forthcoming.

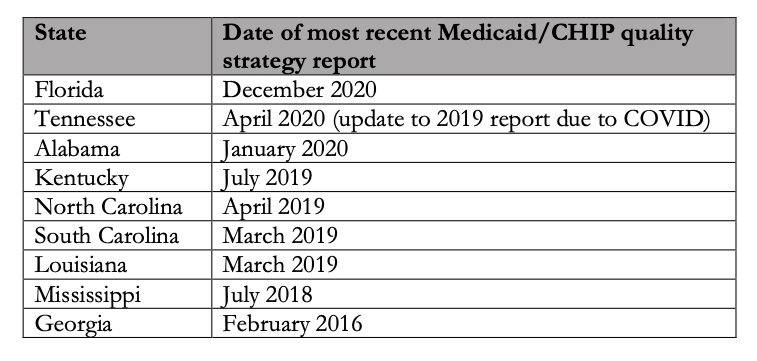

Other Southern states all updated their Medicaid strategies within the three-year-window the federal government requires.

Tennessee updated its plan in 2020, earlier than required, due to COVID. South Carolina’s Medicaid agency will soon update its strategy with changes that reflect the COVID crisis, said an agency spokesperson via email.

When asked about Georgia’s outdated report, Department of Community Health (DCH) spokeswoman Fiona Roberts said in an email that the federal agency that oversees the program — the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) — “is aware” of the situation.

DCH will publish a new quality plan in spring 2021, Roberts added, which will be two years after the 2019 deadline.

GHN reported in December that after consistently submitting information about how its Medicaid program and PeachCare were delivering care, the state for the last two years reported only a fraction of the quality information that federal health officials request.

Since 2016 — when the last quality strategy report was published in Georgia — the Medicaid program has changed in major ways.

Centene, a Fortune 100 company that already owned Georgia CMO Peach State, acquired WellCare, a second state CMO, in January 2020.

Georgia partially expanded Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults, provided they meet certain requirements.

And, back in 2017, Georgia added CareSource to its Medicaid roster. CareSource, a nonprofit corporation headquartered in Dayton, Ohio, now operates in five states.

Some goals missed

Until last week, Georgians lacked data about how CareSource performed on things like postpartum care, childhood immunizations, lead screening, and diabetes treatment. After repeated queries from GHN, Community Health released the missing CareSource report and posted it on the agency’s website. “Thank you for bringing the oversight to our attention,” Roberts, the agency spokesperson, said in an email.

CareSource covers about 237,000 Georgians, or 11% of the state’s Medicaid/PeachCare population. The state paid CareSource $656 million for patient care in 2019, according to a state auditor’s report from last summer.

Out of the 45 adult and child health measures GHN analyzed, CareSource performed the worst of the four companies on 36.

A CareSource spokesman said in a statement Tuesday that “it’s important to recognize that this data is 2 to 3 years old and represents a period of time when we were new to the Georgia market. CareSource went live July 1, 2017, servicing 250,000 Medicaid recipients. Some measures have as much as a two-year window for data to be captured, some of which would precede our [launch]. Additionally, we use the same providers that the other CMOs utilize.”

The company performed the best on four measures: screening for depression among teens; screening for chlamydia among young adult women; blood sugar testing for diabetics; and providing follow-up care for children newly diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Georgia’s most recent quality strategy report — the one from 2016 — said its goal was to improve CMO performance by 10% over 2014 baseline data by 2019.

Georgia Health News compared the latest data from 2018 with the baseline data from 2014. In many cases the state did not meet its goal, and in many other cases performance stagnated.

Jesse Weathington, executive director of the Georgia Quality Healthcare Association, an industry trade group, declined to comment on the performance measures. Roberts of DCH said Tuesday that such data reflect “ongoing opportunity for improvement and the need for continued focus and interventions.”

Maternal and infant health performance

Data on three maternal and infant health measures shows that the CMOs’ performance declined across the board between 2014 and 2018. Georgia faces a well-known maternal and infant health crisis, racial disparities in maternal and infant outcomes, and a shortage of specialist healthcare providers in rural areas of the state.

Rates of timely prenatal care fell for two of the three CMOs that have been in Georgia since 2014. Peach State’s rate dropped most, from 82% to 74%. The only CMO that improved was WellCare, which posted a 2 percentage point increase. CareSource, the newest company, had the lowest rate, at about 70%.

Postpartum care rates also dropped. Peach State’s rate dropped ten points, from 70% to 60%. WellCare’s rate dropped a few points as well, while Amerigroup saw a 1 percent increase. CareSource’s rate was 61%, according to the newly available data.

Low-birth-weight deliveries are those where the infant weighs less than five pounds, eight ounces. Back in 2016, the state said its goal was to decrease the Medicaid low-birth-weight delivery rate to 8.6% by December 2019.

But rates of these baby deliveries actually increased between 2014 and 2018. CareSource had the highest rate, with 9.86%, compared to 9.05% for WellCare, the lowest rate. All four companies’ rates exceeded both the 2014 baseline and the 8.6% goal.

Back in 2016, the state centered its plan to reduce health disparities on lowering the disproportionately high rates of low-birth-weight deliveries among African Americans. DCH does not break its data down by race, so there is no way to tell how well CMOs are addressing the racial disparity.

“We know that Black infants and mothers fare worse for preterm birth, low birthweight, maternal and infant mortality, and a host of other outcomes,” said Amber Mack, research and policy analyst with the Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia.

“The ability to analyze outcomes by race allows us to see if mothers are receiving equitable care or if there’s a need for intervention,” said Mack. “Race and ethnicity should be collected and shared across the board.”

Harker at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute said CMOs “can also invest in solutions that address racial and ethnic inequities…by tracking this data and developing targeted initiatives.”

As of 2018, DCH stopped publishing data on two maternal health measures: frequency of prenatal care, and mental health screening for pregnant women. Maternal depression and substance abuse during pregnancy can have negative effects on both infant and postpartum maternal health. Early intervention can help head off these problems.

“Unfortunately, perinatal behavioral health is not tracked on a statewide level,” said Mack, the policy analyst. “Keeping track of this with CMOs is an opportunity to understand if interventions are working and how we can address the behavioral needs of Georgia’s moms.”

Postpartum depression is “tragic for the mother, particularly if it’s not identified and she’s not treated,” said Kathryne Lockett, a nurse practitioner in Cobb County who sees newborns and their mothers. “If these mothers are depressed, then there’s a ripple impact on their family,” including the new baby, she added.

Children’s primary care

Babies should see a health care provider for a well-child visit at least six times between birth and 15 months, says the American Academy of Pediatrics. But according to the latest state data, only about two-thirds of Amerigroup, Peach State, and WellCare patients met this target. The 2018 rates hovered around 2014 rates, showing little to no improvement. CareSource, the newest of the Georgia CMOs, posted the lowest rate of all, around 39%.

The Academy of Pediatrics also recommends that children between ages 3 and 6 see a doctor at least once a year. Check-up rates for 2018 improved slightly over 2014 for this age group. WellCare posted the greatest improvement, moving from around 67% to 72%. Amerigroup and Peach State improved by about 1 percentage point. CareSource lagged behind, with only about 63% of young children getting adequate check-ups.

Almost all childhood immunization rates dropped. Fewer than two-thirds of Georgia’s Medicaid-enrolled children are getting the full complement of early childhood immunizations. Numbers for this measure dropped across the board: from 67% to 64% for Amerigroup, from 71% to 65% for Peach State, and from 70% to 58% for WellCare. CareSource’s rate was the worst of all: only 37% of enrollees got all immunizations.

Only one immunization rate — that of adolescents receiving vaccines for both meningitis and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) — increased. WellCare performed the best, with a rate of 93%, while CareSource performed the worst, with a rate of 75%.

“Depending on what disease you’re talking about, the consequences [of not vaccinating] can be huge, including hospitalization or even death,” said Dr. Tracy Barr, a pediatrician in Kennesaw. She also noted that if vaccination rates drop below a certain number, “we know that we will have outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease.”

Voices for Georgia’s Children, an advocacy group, noted that Georgia ranked last in the percentage of young children who were on track with all recommended childhood vaccinations in 2019, so the Medicaid numbers are “on trend with Georgia’s general experience.”

“Unfortunately, the trend with worsening childhood immunization rates is not unique to children on Medicaid in Georgia,” said Melissa Haberlen DeWolf, research and policy director at Voices.

DeWolf called the declining rates “extremely concerning” and noted they “seem to correspond with the rise in anti-vaccination misinformation.”

Barr, the pediatrician, also noted that many parents in her office increasingly get anti-vaccine information from social media. Her office will treat children whose parents agree to a delayed schedule for vaccinations, but not those whose parents reject vaccination altogether. Such parents are asked to find another practice because of the risk that unvaccinated children pose to other patients.

“At the very least, having some kind of public health campaign to counteract all the anti-vaccine information that parents are hearing would be a huge help,” said Barr, who suggested the possible use of “TV commercials or Facebook or billboards or mailers that go to these parents.”

Many don’t get routine screening

Developmental screening looks for signs of developmental, social or behavioral problems such as speech issues, problems with motor skills, and even social delays.

More than one-third of children on Medicaid and PeachCare are not receiving early childhood developmental screening. Peach State performed the best out of all the companies, but still only 59% of enrolled children received this crucial screening in the first three years. CareSource lagged behind in 2018 at 45%.

“Early intervention is so important. . . . we don’t want to delay any of these diagnoses,” said Barr.

Screening for lead is another important public health initiative, because exposure to the toxic element can do long-term damage to children’s intellectual development. Only 63% of CareSource enrollee were screened for lead poisoning. The 2018 rates ranged from 78% to 81% for the other three companies, around the same rates as in 2014.

In good news, the CMOs all made big gains in childhood asthma treatment. For example, Amerigroup increased its rates for prescribing the recommended asthma drug combination by 13 percentage points among children and teenagers. People with asthma need a drug to ward off asthma attacks and a separate drug to treat attacks, not just one drug or the other.

Still, though, just above half of Medicaid- and PeachCare-enrolled Georgia children are compliant with their asthma medications at least half the time, and only about one-quarter are compliant at least 75% of the time. CareSource data is not available for this measure.

Childhood asthma is a leading cause of school absences among children, which in turn is a predictor of poor educational outcomes.

“Some of the barriers to medication adherence we hear about most frequently are: lack of transportation (to pick up prescriptions), missed well-child visits and lack of a medical home to coordinate . . . regular access to care, [and] lack of parental understanding about the medication,” said DeWolf of Voices for Georgia’s Children.

“The administrative burden of navigating different [insurance] formularies takes precious time away from busy physicians — time that should be spent with their patients,” said DeWolf

Insufficient treatment of asthma can lead to chronic lung damage, along with increased hospitalizations and resulting increases in medical costs, Barr pointed out.

The CMOs improved their rates of annual adolescent check-ups. The best-performing CMO — WellCare — reported an 11% gain over 2014 baseline data. Despite the gain, though, only 61% of WellCare-enrolled adolescents received adequate care. Rates for adolescents enrolled in the other three plans were even lower, with CareSource posting the lowest rate at 47%.

Rates for screening and developing follow-up plans for depression among teenagers improved dramatically across the board. For example, Amerigroup improved from 2% to 20%, and CareSource had the highest rate of all at 22%. Still, though, the numbers indicate that just a small fraction of teenagers on Medicaid are being screened for depression.

And only between 55% and 61% of children between 6 and 17 years old are receiving follow-up care within thirty days after visiting the emergency room for reasons related to mental illness, according to the state’s 2018 numbers. Data for this age group is not available for prior years.

“It’s terrifying to myself and to my partners the amount of mental health [concerns] that we’re seeing” among pre-teen and teenage patients, said Barr, the pediatrician. “We are in a mental health crisis for our young adults and for our teenagers and even our preteens.”

The trend began before but has been worsened by COVID, she added. Barr said that she sometimes has trouble getting specialist mental health care for her Medicaid patients. She estimates 20-30% of her patients use Medicaid.

Both pediatrician Barr and nurse practitioner Lockett put better transportation and care management on their wish lists for Georgia Medicaid.

“So many of these moms and dads have significant transportation problems,” noted Lockett. Medicaid does provide transportation, but it must be scheduled three days in advance, she said. “It’s a lot of hoops to jump through,” especially in single-parent households or when both parents are working many hours.

“Case managers that can help these patients remain compliant and improve education” would improve outcomes too, said Barr. “Physicians are busier and busier with lots of red tape,” she added.

“I wish that reimbursement was better for Medicaid so that we could see fewer patients and then be able to provide better care,” Barr said.

Rebecca Grapevine is a freelance journalist who was born and raised in Georgia. She has written about public health in both India and the United States, and she holds a doctorate in history from the University of Michigan.