By Judi Kanne

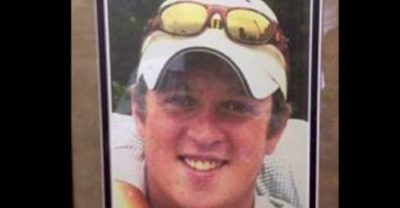

At 23, Jeff Evans was 6 feet 4 inches tall, athletic and known for his charming personality. He was enjoying life, until his health suddenly began to fail.

Even at his young age, Jeff was already a 4-star chef in metro Atlanta, and his mother recalls that he was volunteering at a 2003 charitable event in South Georgia just before their world changed forever.

When he got home from the event, he was not feeling well, as if he had the flu. He tried to rest and recuperate, but after a few days he was showing no real improvement, so his parents took him to the local emergency room.

An X-ray showed his heart to be the size of a small soccer ball.

Jeff’s physicians determined that 80 percent of the functioning capacity of his heart had been destroyed by a recent (and unknown) virus. Within a month, his name was placed on a heart transplant list. He remained on the list until his death in August 2006. He had waited three years for a heart transplant that didn’t happen.

“During the remainder of his life, he took many oral and IV medications in order to keep his ailing heart functional,’’ says Jeff’s mother, Mary Evans. “He tried to live a normal life.”

After his diagnosis, she recalls, Jeff even attempted to go back to the culinary world where he had achieved so much success. But he realized he was no longer able to function in the fast-paced role of a top chef. His condition had robbed him of the energy that was once his trademark.

“Jeff spent his last three days in a hospital room surrounded by the people who loved him,” says his mom.

“Each family member grieves in their own way, and they learned that timing can be different for everyone,” says Evans. “After eight years of processing our grief, we decided to do something as a family that would bring some meaning to Jeff’s loss.”

A way to help others

The Evans family created a housing foundation to help organ transplant patients and their immediate caregivers find a place to live near their transplant hospital in metro Atlanta. Area transplant hospitals include Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston; Emory University Hospital; Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital; and Piedmont Hospital.

Today, Mary Evans serves as executive director for the Jeffrey Campbell Evans Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation, which provides wellness accommodations for transplant patients and their caregivers. Her husband, Bob, is CEO, and Jeff’s brother, Brad, serves as vice president for fund development.

“They have been a part of every decision made since the foundation started,” says Evans. She calls them the “big thinkers” or the “out-of-the-box thinkers.” She considers herself the “day-to-day administrator,” she said.

A difficult adjustment

During Jeff’s stays in Saint Joseph’s Hospital, the Evans family would commute back and forth from their home in suburban Duluth, a trip that could be tiresome if the traffic was bad.

“We called those hospital visits his ‘tune-ups,’ ‘’ says Evans. She would leave work in Duluth at 5 p.m. and drive to the hospital, stay until 11 and then drive home. “The next day, it was a repeat of the same exhausting schedule.”

Today the pace is even more problematic as Americans try to manage transplants within the confines of the unprecedented coronavirus pandemic.

“Organ donations are down by a third,” stated a recent STAT article. “and the health care system itself is in full-blown scarcity, triaging elective surgeries to some unknown future date so only emergency cases find their way into precious operating rooms and intensive care beds.”

As lifesaving as they are, many transplants were being put off. ‘’Organ transplant medicine is always a high-wire act, balancing too many people’s needs with too few matches,” according to the STAT article.

The number of procedures plummeted. But by early June, transplants were almost back to pre-pandemic levels, according to the American Heart Association News.

Seeing where the need was

Looking back on their own experience, the Evans family took time to consider the kind of help that other transplant families would need. While they themselves had sometimes grown weary of their car trips back and forth to Saint Joseph’s, at least they lived in metro Atlanta and were within driving distance of the hospital. They didn’t have to consider moving.

For transplant families who don’t live near a large city like Atlanta, finding a place to stay can be a serious problem. Transplants are usually performed at hospitals in major urban and suburban areas. And based on insurance restrictions, organ transplant patients are often required to relocate to be closer to qualifying hospitals. That can require an out-of-town family to get a hotel room near the hospital — which can cost an average of $4,500 a month — or even try to move to the metro area temporarily.

The Evanses knew that many patients and their families couldn’t afford the change in living arrangements that a transplant procedure required. That’s why they created their foundation, to take the problem of lodging off the table.

Today, the foundation rents and fully furnishes seven 2-bedroom/2-bathroom first-floor apartments, allowing patients and their caregivers to live there at little or no cost (with the help of the Georgia Transplant Foundation).

The usual arrangement is for the family caregivers to move into an apartment first, while the patient is still in the nearby hospital. When the patient is released from inpatient care by the transplant surgeon, he or she moves in with the caregivers. They all stay until the transplant surgeon gives the patient a release to return home. Then they all can head back to their hometown and resume their lives.

From July 2017 to April 2020, the six apartments of the Jeffrey Campbell Evans Foundation (JCEF) served 81 families, with an average occupancy rate of 99 percent. This month, they celebrated the opening of Apartment No. 7 with a ribbon-cutting ceremony.

“If I’d had the seventh apartment ready last month, it would have been occupied within the hour,” says Evans.

Everyday miracles

Upon hearing about Jeff’s life and the foundation, Mike Hall, owner of Georgia Furniture Mart (GFM), offered to help. At Hall’s invitation, the Evans family browsed the Georgia Furniture Mart’s vast selection of furniture, selected pieces that reflected the needs of most renters and received help from GFM’s Michelle Hall, who decorated the new addition for the Evans family. The furniture donation amounted to over $10,000.

The foundation’s long-term goal is to build a standalone transplant house in each of the 38 states that have transplant hospitals, says Evans.

Scott Honan, co-founder of Richmond Honan Development and Acquisitions, LLC, learned of Jeffrey’s story and also offered to help. According to the Evanses, Honan wanted to have his firm design a multifamily-plan apartment building uniquely suited for transplant patients and their caregivers — and he wanted to do it pro bono.

“Actually, I’ll just add a little thought here,” Evans says. “My husband and I believe that we are living in the middle of a miracle every day of our lives.”

The transplant house, which is still in the planning stage, will include 22 apartments — each with two bedrooms and two bathrooms — as well as some common areas, such as a library, offices, storage space “and more of a community environment,’’ says Evans.

“Everything that is happening in this whole process,” says Evans, “is nothing short of a miracle.”

Judi Kanne, a registered nurse and freelance writer, combines her nursing and journalism backgrounds to write about public health. She lives in Atlanta.