By Max Blau

The search for answers over whether waste from America’s largest coal-fired plant has tainted drinking water in a small central Georgia town has united local officials and a riverkeeper group.

The Monroe County Commission and the Altamaha Riverkeeper, an environmental nonprofit that monitors the river’s vast basin, announced plans Friday to hire an independent consulting firm to test dozens of private residential drinking wells in the town of Juliette over the summer.

The testing campaign will seek to confirm the riverkeeper’s previous findings of contamination in well water while running a more comprehensive set of tests for heavy metals.

“We both have the same goal right now,” Fletcher Sams, executive director of the Altamaha Riverkeeper, told Georgia Health News. “That’s to get as much data about the contamination as possible.”

Monroe County Commission Chairman Greg Tapley said in a statement that the new testing campaign would further “the collection of reliable data concerning groundwater quality in the vicinity of Plant Scherer and its coal ash.” Local officials say they hope the data will help them decide whether to sue Georgia Power, which operates Plant Scherer, and other utilities that hold an ownership stake in the plant site.

“Given concerns over potential pollution of groundwater near Plant Scherer, Monroe County is investigating the issue to determine appropriate steps which may be necessary to safeguard the interests of residents and the county,” Tapley said in a statement.

The alliance would have seemed unlikely until recently, because it follows a series of tense town hall meetings and other gatherings where some county officials questioned the validity of findings from the previous well testing campaign by the Altamaha Riverkeeper. And it comes on the heels of the riverkeeper group criticizing the county for scrapping a testing contract with one of the nation’s top coal ash experts because he would not agree to keep any test results confidential.

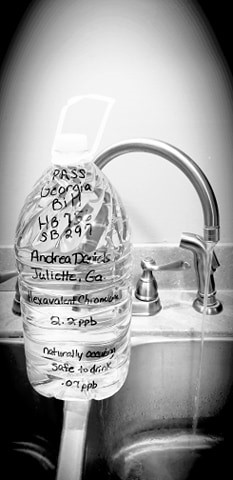

Since last year, Sams tested roughly 100 private drinking wells near Plant Scherer for the riverkeeper organization. Many of those tests found the presence of hexavalent chromium, the toxic chemical that Erin Brockovich found in California drinking wells, and a host of additional heavy metals including mercury, boron, calcium, sulfate and barium — which are indicators of coal ash.

Exposure to some of those contaminants can lead to long-term health risks including kidney damage (from mercury), reproductive system disruption (from boron) and heart issues (from barium).

Since late January, Juliette residents have packed public meetings in churches to organize against Georgia Power. They lobbied local and state lawmakers to support legislation that would force the utility to remove the coal ash and place it in a landfill with a protective liner. They also delivered petitions to Gov. Brian Kemp’s office urging his support on the issue.

Monroe County commissioners responded by trucking in clean water to the area, and began planning for a $16 million project to install water lines throughout portions of the county that have long relied on wells for drinking water.

County commissioners, along with Georgia Power, initially questioned the riverkeeper’s findings. But as more pressure grew, the commissioners sought out independent answers.

In late February, Monroe County officials agreed to hire Avner Vengosh, a Duke University coal ash expert, to test wells around Juliette. But as the scientist prepped his team for the trip to Georgia, the officials ended his contract. He had said he would do the testing only if he could publicize the results, and the officials insisted on confidentiality while pondering litigation.

The county had hoped to receive state support for water testing, but recent events have cast doubt on that. COVID-19 has devastated Georgia’s finances, forcing state agencies to submit plans for double-digit cuts in spending. The previously proposed $500,000 for the Georgia Environmental Protection Division’s water testing efforts may not make it into the final budget.

“I wouldn’t count anything in the House version of the FY21 budget as certain,” Kaleb McMichen, spokesman for Georgia House Speaker David Ralston (R-Blue Ridge), told Georgia Health News recently. “The state will take hits on both the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget, so we will have to wait and see what is and is not possible.”

The EPD declined to comment on the potential budget cuts, which are now pending with the Georgia Senate.

Faced with those uncertainties, local officials reached out to Sams and agreed to forge a partnership, thawing what had been an icy relationship.

“There’s going to be more extensive parameters,” Sams said. “And it’ll be third-party testing — someone from out of state — so there won’t be questioning of the sampling. We’ll also be testing for more heavy metals and a lot of other stuff.”

Sams said the testing is expected to begin this month.

Max Blau is a freelancer working for Georgia Health News.