Brenda Goodman is a senior news writer for WebMD. Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News.

The Environmental Protection Agency has proposed its first of two new rules to curb emissions of cancer-causing ethylene oxide.

Environmental advocates and legislators, however, say the federal agency’s plans won’t do enough to protect people who are exposed to the gas because they live near factories that make it.

The proposed rule updates the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants: Miscellaneous Organic Chemical Manufacturing, commonly known as the MON.

It would require companies to do a better job of controlling their chemical emissions, reducing the cancer risks faced by people who live around manufacturing plants from an estimated 2,000 cases to 200 to 300 cases of cancer for every million people exposed over a lifetime.

The EPA deems cancer risks from air pollution unacceptable when they exceed 100 cases for every million people.

“It’s important that EPA is finally admitting that communities are facing this blatantly unacceptable level of cancer risk,” said Emma Cheuse, an attorney for Earthjustice, a nonprofit law firm that represents clients in environmental lawsuits free of charge.

But Cheuse said the new rules aren’t adequate.

“It’s unbelievable that EPA is proposing to leave certain communities exposed to a level of cancer risk that is 2 to 3 times the level the EPA deems presumptively unacceptable,” she said.

While the new rule deals with more than one chemical, some of its most anticipated impacts relate to ethylene oxide.

Ethylene oxide is a base chemical that’s used to make other chemicals. It’s also used in a wide variety of consumer products — everything from inks and paints to antifreeze and detergent. It’s also used in gas form to fumigate about half of all sterile medical products in the U.S.

The use of ethylene oxide has largely occurred out of the public eye. But in 2016, the science arm of the EPA — which had been conducting a long-term study on the chemical’s safety — determined that it was 50 times more cancer-causing than previously known. The agency updated a key number used to assess risk from the chemical.

In 2018, the EPA published a report that, for the first time, used the updated risk value.

The report, called the National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA), determined there were 109 census tracts in about 20 communities across the U.S. that had higher cancer risks from airborne toxic chemicals than the agency considered acceptable. Most of that risk was driven by ethylene oxide.

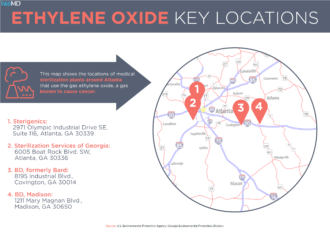

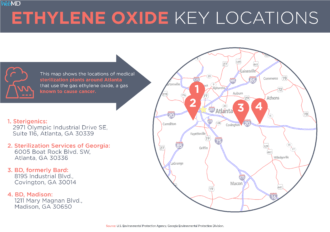

Three of those census tracts were in metro Atlanta — two in Fulton County, near the Cobb County town of Smyrna, northwest of Atlanta, and another in Covington in Newton County, east of Atlanta. Both areas are near facilities that use ethylene oxide gas for sterilization.

This new rule applies to facilities that manufacture ethylene oxide. A separate standard covers emissions from commercial sterilizers. The EPA is expected to announce plans to revise rules on the commercial sterilizers soon.

About half of the census tracts flagged by the NATA report as having higher-than-acceptable cancer risks because of ethylene oxide are near commercial sterilizing facilities, and the other half are near chemical plants, according to Mike Koerber, deputy director of the EPA’s office of Air and Radiation, who testified before an FDA advisory panel on Tuesday.

One example of an affected community is Kanawha County, WV, which is near facilities that manufacture ethylene oxide. There, the EPA has estimated that cancer risks across five census tracts range from 70 to 335 cases for every million people exposed to ethylene oxide emissions over a lifetime. Other manufacturing hot spots are in Texas and Louisiana.

By law, the EPA is required to review and update these standards every eight years. But the agency fell behind schedule, and this is the first update to the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants for the MON since 2006. The agency is under a court order to finalize the rule by March 2020.

The first part of the process requires the EPA to estimate risks to communities. In a second step, the EPA reviews available technology to control these emissions to see if more could be done to control them.

In its review, the EPA said it found nine facilities that release ethylene oxide from vents, storage tanks and equipment leaks.

The agency has proposed new controls for these problem areas. But it doesn’t require fence-line air monitoring, which is periodic air testing around the perimeter of a facility. This kind of air testing alerts companies when emissions are present in outdoor air and spreading into the community.

In contrast, the EPA required fence-line monitoring around petroleum refineries in 2015.

“These are common-sense measures,” Cheuse said of fence-line monitoring rules. “Communities have called for years for that. It assures protection for public health and safety and really strengthens compliance.”

Cheuse also said more could be done to improve leak detection and repair, including optical imaging, which uses special cameras to detect chemical plumes, which she said should have been included in the proposed rule.

The Ethylene Oxide Panel of the American Chemistry Council, an industry group, said in a statement Friday that it will be reviewing the EPA proposal.

“Ethylene oxide is a versatile and valuable compound that’s used to help make countless everyday products,’’ the statement said. “We understand and appreciate the concerns that people have about the air they breathe. No one should have to question whether the air they breathe is clean. That’s why companies that make and work with ethylene oxide are actively investing in research and cutting-edge product stewardship technologies — so that we can continue to help protect the health of our communities. As a result of these actions, industrial ethylene oxide emissions have already fallen nationwide by over 80% since 2002.”

In a joint statement, U.S. Senators Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin, both Democrats from Illinois, were critical of the proposed EPA rule. Illinois, like Georgia, has seen community protests and government action against medical sterilizing plants that use ethylene oxide.

“We are alarmed that the agency is even considering rubber-stamping weak standards that would continue to expose our constituents to elevated cancer risks. It is also unacceptable that EPA is failing to propose fence-line monitoring after dangerous malfunctions have been reported at EtO [ethylene oxide] facilities,” Duckworth and Durbin wrote.