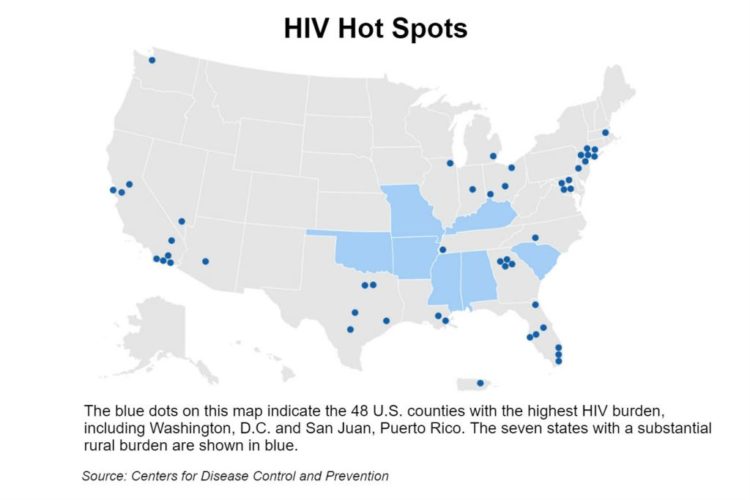

The map of the United States shows four blue dots clustered in northern Georgia. They represent the metro Atlanta counties of Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett and Cobb.

It’s not exactly surprising that the four — the most populous in our state — are among 48 counties in the nation that the Trump administration is targeting for its plan to stop the spread of HIV.

President Trump announced the plan in his State of the Union address last week.

HIV is the virus that causes AIDS, a disease that has killed millions around the world. Much progress has been made in keeping patients alive by thwarting the development of the full-scale disease, but a key to anti-HIV strategy is preventing new infections.

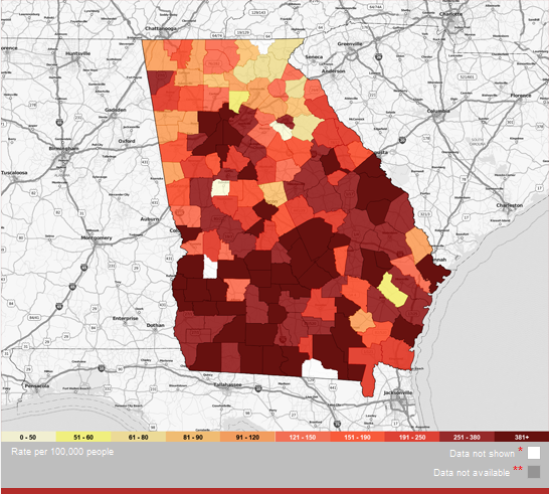

Georgia is the No. 1 state in rates of new infections, and metro Atlanta is No. 3 among metropolitan areas, says Dr. Wendy Armstrong of Emory University, and medical director of the Infectious Disease Program at Grady Health System. Grady’s Ponce de Leon Center, which provides HIV services, has 6,200 “active’’ patients, and the number is rising, Armstrong says.

“We have a huge epidemic, a lot of new infections,’’ says Dr. Carlos del Rio, chair of the Department of Global Health and professor of epidemiology at Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health.

“We were in the state of inertia’’ in the fight against HIV, adds del Rio, also professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory School of Medicine. “Hopefully [the White House initiative] will light a fire.”

The administration’s plan will deploy the people and prevention and treatment strategies needed to reduce new HIV infections by 75 percent over the next 5 years, with the hope of a 90 percent reduction within 10 years, according to the CDC’s director, Dr. Robert Redfield.

More than 50 percent of new HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2016 and 2017 occurred in 48 counties, Washington, D.C., and San Juan, Puerto Rico, said the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The plan would increase investments in these hot spots through existing programs like the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, which provides care to low-income uninsured people, NPR reported. The federal government would provide funds to create a local “HIV HealthForce” in these targeted areas to expand HIV prevention and treatment.

“Almost 90 percent of new infections are transmitted by people who do not know they are infected or who are not being retained in treatment,” said HHS Secretary Alex Azar.

The Trump administration initiative has raised hopes among community leaders here in Georgia.

“We can definitely end the epidemic within the next decade,” says Daniel Driffin, 32, who co-founded Thrive SS, a nonprofit that provides support services to 900 African-American men in Georgia who have HIV.

Adds Larry Lehman of Positive Impact Health Centers, an HIV services provider: “The true test will be if the White House and Congress appropriate the necessary funds needed year over year to end this epidemic.’’

Besides the 48 county “hot spots’’ designated by federal health officials, they are targeting seven states with high rates of the disease in rural areas. There’s a Southern feel to them: Oklahoma, Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas, Alabama, South Carolina and Mississippi.

According to the CDC, more than half of the new HIV diagnoses in 2016 – about 20,000 — were in the South. Of those Southern cases, two-thirds were from male-to-male sexual contact, Dr. Eugene McCray, director of the CDC Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, said at a Center For AIDS Research symposium at Emory in November. One in five new diagnoses were among women.

This region has the highest death rate from HIV infection. More than 1 million Americans live with the virus.

Factors leading to high HIV numbers in the South include a social stigma surrounding the disease; poverty; lack of insurance and access to care; and no Medicaid expansion in most Southern states. McCray said income inequality, discrimination and poorer health outcomes are more widespread in the South.

Driffin, who has been living with HIV for 10 years, underscores the access-to-care problem. Southern states in general have higher rates of people without health coverage.

“Access to care can be a problem for black and brown people in the Deep South,’’ says Driffin.

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act would extend insurance coverage to many people with HIV, experts say. Most states have adopted expansion, making more low-income people eligible for the program, but Georgia’s elected leaders have consistently rejected that as too costly.

Increasing use of a vital drug

“Many people often go without meds,’’ Driffin says. “If we increase care [through expansion], we can drive down new infections. We can stop new infections if we supply PrEP’’ more broadly, he adds.

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is a drug used to prevent HIV. Through daily use, people at high risk of getting the virus can lower the chances of becoming infected.

An early pioneer in HIV/AIDS prevention, Dr. James Curran of Emory, says early diagnosis and treatment are crucial, along with having patients remain under care. For the HIV initiative to work well, strong coordination is needed among federal, state and local officials, says Curran, dean of the Rollins School of Public Health and co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research.

Another challenge is the shortage of HIV providers – doctors, nurses and others specializing in this work.

Since the initiative was announced, there has been some skepticism voiced.

Several HIV/AIDS advocates say the goal is achievable, but only if the administration reverses course in several major areas of health care policy, including efforts to weaken the Affordable Care Act and cut funding for Planned Parenthood, and unless it changes other policies they consider discriminatory, NPR reported.

“This effort cannot move existing resources from one public health program and repurpose them to end HIV without serious consequences to our public health system,” Michael Fraser, CEO of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said in a statement.

CNN reported that New York City health commissioner, Dr. Oxiris Barbot, said in a statement Wednesday:

“President Trump’s pledge to end the HIV epidemic within 10 years is encouraging, but it is difficult to reconcile this statement with his administration’s systematic assault on the HIV community — including undermining access to affordable health insurance and HIV drugs; cutting funds for HIV research; and attacking LGBTQ+ people.”

Despite such criticism, Dr. Brett Giroir, assistant secretary for health at HHS, said he is confident there will be “sufficient resources” in the 2020 budget for the new HIV/AIDS plan.

The CDC’s Redfield said in a statement, “We will listen to people living with HIV, and to public health partners in the most affected communities, so we reach those in greatest need.’’

HIV experts say getting communities involved will be important.

“For years we have lacked adequate resources to end the epidemic,’’ Lehman says. “ We need to support the continuum of wrap-around services to keep patients in care as well as expanding wrap-around services to support patients on PrEP.’’

Emory’s Armstrong and del Rio are hopeful about the anti-HIV effort reducing the number of new infections.

The anti-HIV campaign “transcends politics,’’ Armstrong says.

Adds del Rio, “This is not a Republican or Democrat issue. This is an American issue.’’