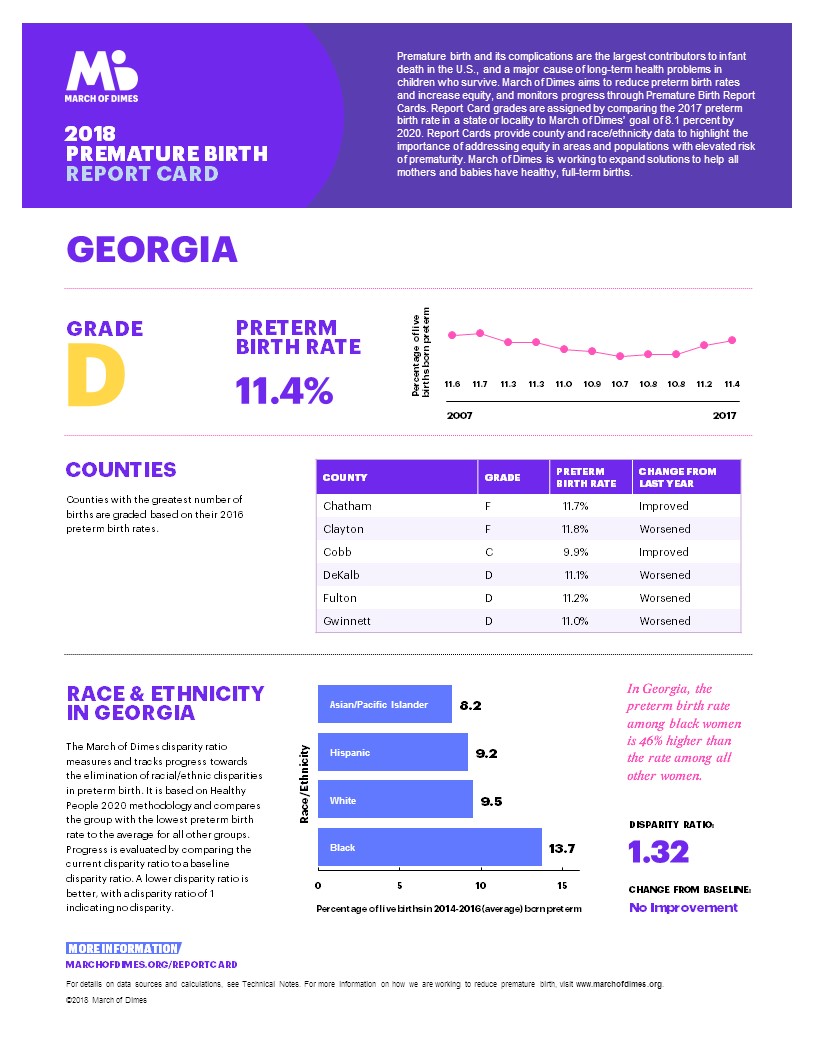

Georgia’s preterm birth rate rose from 11.2 percent to 11.4 percent in 2017, keeping the state at a “D’’ grade in the annual Premature Birth Report Card from the March of Dimes.

The state’s rate of babies born too soon (before 37 weeks of pregnancy) continued to reflect large racial disparities, with black women at 13.7 percent – 46 percent higher than the rate among all other women.

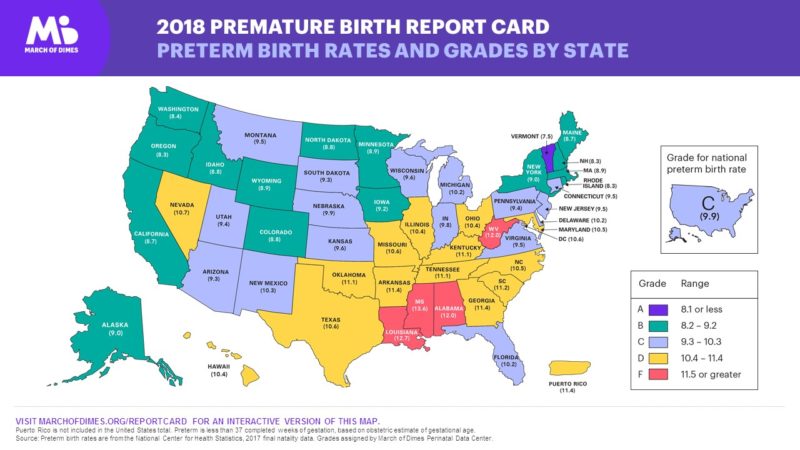

The overall U.S. preterm birth rate also rose, reaching 9.93 percent of births in 2017 from 9.85 percent in 2016, according to the report, released Thursday.

Thirteen other states received a “D’’ grade from the March of Dimes, a nonprofit focused on maternal and infant health. Four states — Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and West Virginia — received an “F.”

Preterm birth is the largest contributor to infant death. And babies who survive a premature birth often face serious and lifelong health problems, including breathing problems, jaundice, vision loss, cerebral palsy and intellectual delays. Preterm birth accounts for more than $26 billion annually in avoidable medical and social costs, according to the National Academy of Medicine.

The March of Dimes report card also gave individual grades for the six Georgia counties with the most births in 2016. Chatham and Clayton received an “F,’’ though Chatham’s preterm rate improved; DeKalb, Fulton and Gwinnett each got a “D,’’ with a higher preterm rate in each; and Cobb earned a “C,’’ with an improved rate.

Bibb County, which was not graded, had a 14.1 percent preterm birth rate, said Denise McLaughlin, of the March of Dimes Georgia chapter.

The causes of preterm birth are varied, said McLaughlin, a retired nurse midwife. Among them are a lack of health insurance, and limited access to supportive care before, during and after pregnancy, she added.

Other factors include the health of the pregnant woman and whether she has conditions such as hypertension or diabetes. And if a woman has already had a preterm birth, she stands a greater chance of having one in the future.

Intervals between pregnancies also make a difference. Georgia mothers who have less than one year of spacing between delivery and the next pregnancy have a higher preterm birth rate, according to the Department of Public Health.

“Women who have a low socioeconomic [status] have higher preterm birth rates,’’ McLaughin said.

Access to obstetrical care is a problem in Georgia.

Longer distances to birthing hospitals can increase chances for preterm birth. But currently, only 59 of Georgia’s 159 counties have labor and delivery units, with about 75 hospitals in the state routinely delivering babies, according to the Georgia OBGyn Society.

Dr. Hugh Smith of Thomaston, who is immediate past president of the Georgia OBGyn Society, said that “unfortunately, this report shows a worsening trend during a critically important time in the life cycle.’’

“Women’s health professionals must continue to advocate for improved access to health care for women in Georgia and strategies to increase the numbers of women’s health professionals in Georgia,’’ Smith said.

“Currently, more than half of Georgia counties do not have a practicing obstetrician. Additionally, Medicaid reimbursement for group prenatal care would be extremely beneficial to improving birth outcomes.”

To earn an “A’’ grade, a state must have a preterm birth rate less than or equal to 8.1 percent. Only Vermont received the top grade in the 2018 report card.

The March of Dimes is supporting Centering Pregnancy programs, which provide group prenatal care that combines health assessment, education and support, in Macon, Thomaston and Columbus.

Public Health said it’s leading several initiatives on infant health, including a collaborative involving physicians and birthing hospitals set to focus on severe hypertension in pregnancy.

Georgia has six regional perinatal centers that provide a system of coordination for transport of high-risk mothers and infants to higher level of care facilities when indicated to increase survival rates and improve birth outcomes, said Public Health spokeswoman Nancy Nydam.

DPH began an initiative in 2014 to increase access to long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods. And the department launched a campaign earlier this year to increase awareness of family planning services available in local health departments.

The 2018 national report cited signs of progress in several states. They include:

** Rhode Island: Increased leadership and collaboration among Rhode Island’s Department of Health, the March of Dimes, and health care systems in the state led to a full percentage point drop in the premature birth rate, moving the nation’s smallest state from a ‘’C’’ to a “B’’ grade.

** Knox County, Tenn.: Wider use of locally developed programs, such as group prenatal care, helped Knox County lower its preterm birth rate from 12.5% in 2007 to 9.9% in 2016, an improvement of more than 20% over the past decade.

** Raleigh, N.C.: Adoption of the North Carolina Pregnancy Medical Home model, which coordinates care for pregnant women, helped the city tackle early elective deliveries and smoking, forcing Raleigh’s preterm birth rate down from 9.9% in 2015 to 9.3% in 2016. Late preterm births also decreased from 6.9% to 6.1%.