The next time you’re at the grocery store, stop and look at the nutrition labels. You may notice a few changes.

Although new labels authorized by the Food and Drug Administration are not yet required by law, a few companies are already beginning to put out products with updated wording.

“We are keeping the iconic look of the label but are making important updates to ensure consumers have the information they need to make food choices that support a healthy diet,” Deborah Kotz, the FDA’s Labeling media contact, said in an email to Georgia Health News.

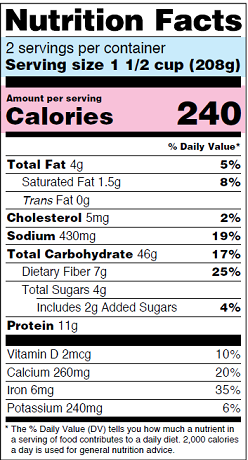

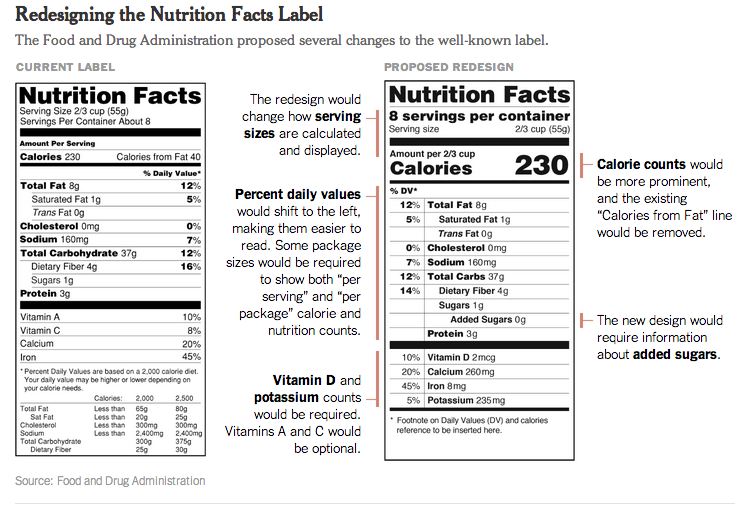

To help consumers read nutritional information more easily, there is now bigger type for printed information such as “calories,” “servings per container” and “serving size,” as well as for the listings of the amounts of vitamin D, calcium, iron and potassium. Also, the labels now include the amount of “added sugars” (in grams), while they no longer list the “calories from fat.”

“The FDA finalized the regulation for the new Nutrition Facts label for packaged foods in 2016 to reflect updated scientific information, including the link between diet and chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease,” Kotz said. “The new label will make it easier for consumers to make better-informed choices.”

The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 required nutrition labels to be on most foods regulated by the FDA, and that nutrient content or health claims be consistent with agency regulations. These regulations were implemented in January 1993. In May 2016, the FDA proposed changes to nutrition labels, and now those changes are taking effect

The changes came after the FDA reviewed updated information on nutrition, as well as national survey data. The goal of the changes is to reduce the risk of chronic health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, high blood pressure and stroke, Kotz said.

Knowledge of what constitutes a healthful diet has changed over the years.

For instance, sugar is now a greater cause for concern. “Scientific data shows that dietary patterns lower in sugar-sweetened foods and beverages are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease,” Kotz said. “In addition, it is difficult to meet nutrient needs while staying within calorie limits if you consume more than 10 percent of your total daily calories from added sugar.”

On the other hand, studies have shown that fat in the diet is not as bad as was believed a number of years ago, and that’s why the “calories from fat” entry is disappearing from labels.

People eat differently today than they did 20 years ago, and the FDA is updating its serving size requirement to accurately reflect what people eat and drink currently, Kotz added.

‘It’s going to take education’

Labels are important, but consumers need a frame of reference, a basic understanding of nutrition. “People have to know what all that stuff on [the labels] means,” said Mary Ann Johnson, the University of Georgia’s Flatt Professor in Foods and Nutrition.

“If you have no idea how many calories you’re supposed to eat a day, it’s just meaningless,” she said. “For sugar, we have the same problem. If you don’t really know what those numbers mean, they’re not really going to help you. It’s going to take education along with the labeling.”

The American Heart Association recommends no more than 36 grams of added sugar per day for men and no more than 25 grams of added sugar per day for women.

Natalie Adan, the Georgia Department of Agriculture Food Safety Division Director, said the department is informing new Georgia businesses about the change. The University of Georgia’s Food Science Extension does nutrition labeling as a service and is already using the new labeling.

The new labels were set to be required by July 2018, but some companies, including Mars, Nabisco, PepsiCo and KIND, have already started placing them on their products.

Some companies, though, objected to the implementation of these rules, and in October, the FDA issued a proposed rule to extend the compliance dates from July 26, 2018, to January 1, 2020. For manufacturers with annual food sales of less than $10 million, the dates changed from July 26, 2019, to January 1, 2021.

The proposal suggests that changing the date would ensure all manufacturers have time to address technical questions to print updated Nutrition Facts labels.

According to the FDA’s website, it extended the compliance dates “to provide the additional time for implementation. The framework for the extension will be guided by the desire to give industry more time and decrease costs, balanced with the importance of minimizing the transition period during which consumers will see both the old and the new versions of the label in the marketplace.”

Disputes and shifting alliances

Many food associations initially fought against the updated labels. But after the FDA’s proposed rule to change the compliance date, the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), one of the country’s top food-lobbying groups, released a statement: “FDA’s proposed new compliance date will provide companies with the necessary time to execute these updates to the Nutrition Facts Panel in a manner that will reduce consumer confusion and costs in the marketplace,” said GMA’s president and CEO, Pamela G. Bailey. She called it a “common-sense extension.”

Some companies did not agree with her.

In September, the Campbell Soup Company announced it would withdraw from GMA by the end of the year, and in October, the company joined the Plant Based Foods Association, an organization that advocates on behalf of companies that want to sell “alternatives to animal ingredients and products.” The group aims to eliminate policies, such as labeling restrictions, that put plant-based foods at an economic disadvantage, and to change the debate on public policy issues such as dietary guidelines.

Campbell’s is the biggest company to join the PBFA, which launched in March 2016 and currently has 98 company members. It’s not solely for marketers of vegetarian products. “We don’t require companies to be 100 percent plant-based to be members,” Michele Simon, PBFA’s executive director, said in an email.

As its reason for leaving GMA, Campbell’s cited the group’s lack of interest in labeling foods that contain GMOs, or genetically modified organisms.

Oklahoma State University’s July 2016 Food Demand Survey showed 81 percent of consumers support mandatory labels for GMOs. Whatever the merits of the controversy over these products, Campbell’s departure from GMA may show the company’s increased willingness to heed consumers’ demands.

Campbell’s Bolthouse Farms launched its Plant Protein Milk line in September. According to Simon, one of PBFA’s 2018 goals is to stop the Dairy Pride Act, legislation supported by the dairy industry that aims to keep nondairy products from using the terms “milk,” “cheese” or “yogurt.” Before joining PBFA, Campbell’s in-house counsel had already begun working with the association to stop the Dairy Pride Act.

“Campbell’s is sending a pretty strong signal that they’re trying to dedicate themselves to simpler, fewer ingredients in their products,” said Joshua Berning, a University of Georgia professor who researches food marketing and consumer demand for food products.

“They’re trying to provide foods that appeal to a certain market segment that previously was looked at as more of a niche,” he said. “Campbell’s is saying that they’re going to dedicate themselves to selling that product line as opposed to buying a company that does that for them.”

In October 2017, Nestlé, the world’s largest food company, announced it was leaving GMA at the end of the year.

“Companies pay membership dues to GMA based on their revenues, which gives GMA more lobbying power,” Berning said. The Nestlé pullout from GMA, he said, is major blow to the group, “because Nestlé owns way more food companies than Campbell’s, across way more food supply chains.”

Unilever, Tyson Foods, the Kraft Heinz Company, Dean Foods and Mars also decided not to return to GMA in 2018 due to disagreements about how to advocate for several federal regulations, signaling more changes in the food industry.

Will more labeling be beneficial to consumers? Berning isn’t sure.

“I think there’s a lot of misperception about what any of the labels or information means,” he said. “Unfortunately, I think that narrative is driven a lot more by market and a little bit of fear-mongering towards science. Consumers still want more transparency with what’s in their foods. [These companies] are responding and saying, ‘We’ll give you more of that transparency’.”

Emily Webb is a graduate student at the University of Georgia pursuing a master’s in journalism. She has a special interest in nutrition and health.