The federal decision to end “net neutrality’’ rules has sparked concerns about potential damage to rural health care.

The central question: Will repeal of the rules harm the burgeoning telemedicine movement in Georgia and other states?

The Federal Communications Commission voted in December to scrap the net neutrality regulations it created a few years ago that prohibit broadband companies from prioritizing or blocking some content over others.

Rather than treat all Internet traffic equally, telecom companies will be able to divide the web into slow and fast “lanes.” The companies could charge more for faster connections.

A slow lane, though, would disrupt the strong connectivity needed for telemedicine, Mei Kwong of the Center for Connected Health Policy told GHN in an interview Friday. “Without that connectivity, telemedicine doesn’t work,’’ she said. “You need it on the patient end and the provider end.”

Telehealth has increased over the past five years in rural America as technology has improved, Kwong said.

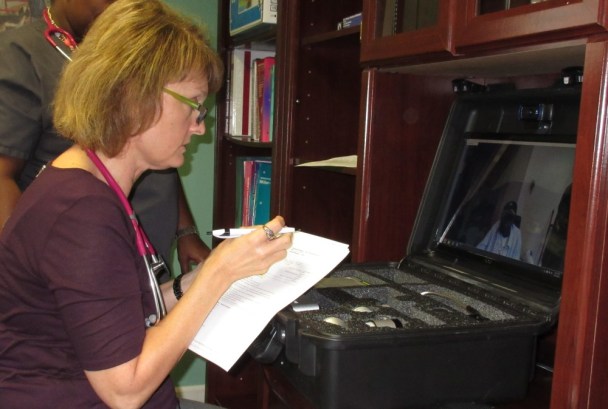

That technology allows two-way, real-time interactive communication between the patient and a medical provider at a distant site.

Nearly 1 million Americans are currently using remote cardiac monitors, according to the American Telemedicine Association.

And through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, more than 700,000 veterans made more than 2 million telehealth appointments last year.

The FCC’s repeal comes at a time when rural health care is getting increased focus at the Georgia General Assembly. There are major shortages of doctors and other medical providers in rural parts of the state, and financial struggles have caused closures of some rural hospitals in recent years.

Telemedicine, meanwhile, has helped fill in some of these medical gaps. And the Georgia House Rural Development Council is pushing for increasing broadband access across rural areas of the state, an initiative that may bolster telemedicine.

Last week, when asked about net neutrality, Georgia House Speaker David Ralston (R-Blue Ridge) said the state had not made a thorough evaluation of how the FCC move will affect rural health care.

“Telemedicine, we all recognize, is going to be a larger part of our health care future,’’ Ralston told reporters. “But it’s not going to be in areas where you don’t have high-speed internet.”

These connections can deliver needed medical services to schools, homes, ambulances and other remote sites, says Jimmy Lewis, CEO of HomeTown Health, an association of rural hospitals in Georgia.

“It levels the specialist shortage [for rural patients] by providing access remotely to cardiologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists’’ who are in urban areas, Lewis said.

Many areas of the state have no mental health providers, but telemedicine has brought this care to rural areas.

Dr. Jean Sumner, dean of the Mercer University School of Medicine in Macon, is a strong proponent of telepsychiatry, through which psychiatric assessments and care are delivered through videoconferencing. In her practice in Wrightsville and Sandersville, Sumner said recently, “it worked extremely well for patients.’’

Rural areas of the nation have seen a rise in suicide rates, the CDC recently said.

And in the case of a stroke, a fast connection to a health care provider “can be lifesaving,’’ Kwong says.

Some fear that the repeal may create a two-tiered “haves vs. have-nots’’ scenario, in which a rural medical provider can’t afford the fast-lane services, while a large urban health system could.

Clinics in rural areas “don’t have a lot of cash,’’ Kwong said. “Do they have the money to pay for that connectivity?”

In July, the American Academy of Family Physicians sent a letter to FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, saying, “the Internet forms the backbone on which the health care industry is building capabilities for health information exchange. Lack of health information exchange is literally life-threatening. It is paramount for the health and well-being of U.S. citizens that no barriers be placed hindering the free and open appropriate exchange of health information.”

Pai, who supported the net neutrality repeal, said last year that the proposal has the potential to support access to telehealth.

“One aspect of this proposal I think is worth highlighting here is the flexibility it would give for prioritizing services that could make meaningful differences in the delivery of health care,” Pai said at a November conference. “By ending the outright ban on paid prioritization, we hope to make it easier for consumers to benefit from services that need prioritization — such as latency-sensitive telemedicine.”

Last month, Pai complained of misinformation surrounding the issue. “What I can say is that the hysteria [over the repeal] has reached a pitch which is completely disproportionate to the facts,’’ he said, according to the Washington Post.

Pai and other defenders of the repeal say it simply restores the former status quo, and they say policies as significant as net neutrality should be established by Congress, not regulators.

Amid the debate, U.S. Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) has proposed a measure called the Open Internet Preservation Act, which has drawn fire from net neutrality advocates. Other members of Congress are looking at the issue.

The new FCC rules have not yet been published.

There has been speculation that health care will be exempted from the repeal, so that all applications will have “fast lane’’ connectivity.

But Kwong says she questions how that exemption would work in settings that are not traditionally linked to health care, such as a school or a patient’s home.

Meanwhile, states are moving to write their own net neutrality regulations, The Hill reported recently.

California, New York and Washington state are pushing their own versions of net neutrality rules, and more state governments are expected to do the same, according to The Hill, citing a report from Fast Company.