A clinical trial that involved Emory University and Grady Memorial Hospital may help produce an effective treatment for thousands of stroke victims nationally.

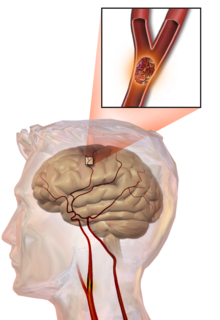

For patients suffering a stroke, which occurs when blood flow to an area of brain is cut off, current guidelines recommend blood clot removal only within six hours of the onset of the event.

But the international study, whose results are published in the New England Journal of Medicine, shows that clot removal up to 24 hours after a stroke led to reduced disability for certain patients.

To select patients for the trial, the researchers employed a new approach that was not based only on the length of time elapsed since the stroke, but took into account brain imaging and clinical criteria.

The DAWN trial randomly assigned 206 people who arrived at the hospital within six to 24 hours of a stroke event. Some were given clot removal therapy, known as thrombectomy, while others got standard medication therapy.

Almost half of the patients (48.6 percent) who had clot removal showed a considerable decrease in disability, meaning that after 90 days of treatment they could independently handle activities of daily living.

Only 13.1 percent of the medication group had a similar decrease in disability.

“After six hours [since a stroke began], many people thought all the damage was done. We didn’t agree with that,’’ said Dr. Raul Nogueira, professor of neurology, neurosurgery and radiology at Emory University School of Medicine. Nogueira, one of the two principal investigators in the trial, is also director of neuroendovascular service at the Marcus Stroke & Neuroscience Center at Grady Memorial Hospital.

Many victims first show the symptoms of their stroke when they wake up in the morning, Nogueira said. For them, it’s not known precisely when the stroke occurred, so the six-hour window can’t be used, and they typically are left out of the clot removal protocol under the current guidelines, he told GHN.

He compared strokes to forest fires, with various factors determining their severity.

Under windy conditions “forest fires spreads very fast,’’ Nogueira said. But under different conditions, fires don’t burn the same way.

“Not all fires are equal,’’ he said. “Not all strokes are equal.”

The discovery that blood clot removal can be beneficial much later than previously believed is extremely important, Nogueira said. “These findings could impact countless stroke patients all over the world who often arrive at the hospital after the current six-hour treatment window has closed.’’

“This is a paradigm shift,’’ he said. “It allows us to treat more patients.”

Of the 206 study participants, 38 were Grady Stroke Center patients, he said.

Dr. Jeffrey Switzer, stroke specialist in the Medical College of Georgia Department of Neurology, who was not a part of the study, said the DAWN trial “is a very big breakthrough in how we take care of acute stroke patients.’’

A second study is expected to show similar results, Switzer said. “It will rapidly become the standard of care.”

Switzer estimated that the new guidelines could help thousands of patients a year in the United States.

The DAWN trial, which lasted from September 2014 to February of this year, included trial locations in Spain, France, Australia and Canada. The trial was sponsored by Stryker Corporation, a medical technology company that manufactures the clot removal devices used in the study.

The researchers planned to enroll a maximum of 500 patients over the study period. But an interim review of the treatment effectiveness after 200 patients were enrolled led the independent Data Safety Monitoring Board overseeing the study to recommend an early termination of the trial, based on the data showing clot removal provided significant clinical benefit in the patients.