PART ONE OF SPECIAL REPORT

By Brenda Goodman, Andy Miller, Erica Hensley, and Elizabeth Fite

Brenda Goodman is a senior news writer for WebMD and Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News. Freelance writers Erica Hensley and Elizabeth Fite also contributed to this report. This investigation was supported by a grant from the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation.

In water, lead is a ghost poison. It has no taste or smell. It’s usually invisible. And it can stay in plumbing for years, gradually dissolving and flaking off into water we use for cooking and drinking.

Lead was banned from plumbing decades ago, but as the crisis in Flint, Mich., has shown, the threat remains.

“It never even dawned on me that we would have lead in our pipes,” says Allison, a homeowner in Sandy Springs, an affluent suburb of Atlanta, who asked us not to use her last name.

Allison’s home, a stately brick residence, is valued by the real estate website Redfin at more than $1 million.

In 2015, tests by the Atlanta Water Department – which supplies water to Sandy Springs – found levels of lead in Allison’s water that were over the EPA’s limit.

While the lead in her water was not welcome news, Allison at least found out she had a problem, because the testing worked. In plenty of other water utilities around Georgia and the U.S., the system for testing lead in water is not working as it should, leaving people uninformed and unprotected.

We reviewed lead testing records obtained through the Open Records Act for water systems in Georgia serving at least 10,000 people. Together, they provide water to about three-quarters of the state’s population. We then compared lead testing addresses to property records for the same locations.

We found a process hindered by poor record-keeping and an apparent failure to follow a federal rule that’s been on the books for more than 25 years.

We reviewed lead testing records for 105 water systems:

** About half — 58 — have tested some sites at lower risk for lead problems instead of focusing solely on those at highest risk.

** 49 of those water departments had also labeled some lower-risk sites as higher-risk, giving the appearance they were following testing guidelines.

We asked the EPA what could happen to water system employees who mislabeled test sites. In an email, EPA press officer Dawn Harris-Young said they could face punishments ranging from a written reprimand called an administrative order to fines and even jail time (if prosecuted) in cases where EPA can prove that a water system “purposefully and willfully falsified documentation.”

Our results surprised one national expert.

“It’s a very significant finding that, to my knowledge, has not yet been reported” on a statewide level, says Yanna Lambrinidou, PhD, an anthropologist in the civil and environmental engineering department at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va. Lambrinidou has investigated lead problems in cities around the U.S.

Georgia’s testing practices have attracted the attention of the EPA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG), an independent watchdog that polices the agency, according to internal emails obtained under the Open Records Act. In a November 2016 email, the OIG asked state officials to explain how they “ensure that the high-risk homes are sampled for lead,” and about other challenges with lead sampling.

The OIG’s office confirmed that its questions were part of an evaluation of Georgia’s program, and they said they expect to make their findings public later this year.

Here are some examples of what we found:

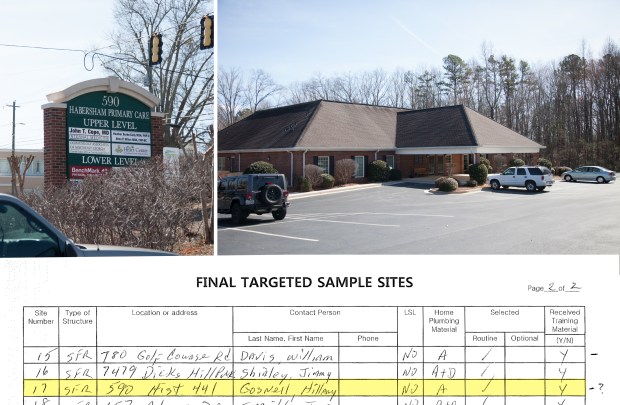

** The Northeast Georgia town of Demorest tested 30 addresses for lead in 2015. Only 10 were homes.

Others included a hair salon, convenience stores, two doctors’ offices, a fire house, metal fabricator, a well driller, the police department and City Hall. We couldn’t identify four other test addresses.

Although commercial sites may be tested under EPA rules, it’s only allowed if a water system first runs out of highest-risk homes.

** That same year, the Southwest Georgia city of Albany tested seven businesses for lead but labeled them on test forms as single-family homes.

** The Notla Water Authority, which serves customers in Union County in North Georgia, tested the homes of at least seven people who were employees or board members of the water department in 2015, though only one had a home in the high-risk category. It also tested a gas station, a marina boathouse, and a service garage owned by the Water Authority, but labeled them as private homes.

** In Lawrenceville, a suburb of Atlanta, water system employees said that to the best of their knowledge, they have been testing their town’s highest-risk homes, even though they admitted they don’t have the records to verify those locations.

** Savannah, Georgia’s oldest city, has also lost track of its highest-risk homes. Water officials said they could not determine with any certainty what kind of plumbing was in the homes they test because the records are lost.

Lead testing issues aren’t unique to Georgia.

In 2015, local and state officials in Flint said they were testing homes at highest risk for lead problems, when many of the homes they tested were actually at lower risk. State regulators also asked a local water operator to drop high results from its testing, hiding the problem. As a result, the widespread contamination in Flint went undetected for months longer than it should have, delaying actions to fix the problem, according to MLive.com.

One study found that the percentage of children with elevated lead in their blood doubled in Flint after lead levels climbed in the city’s water supply. The increase was linked to a change in the city’s water source, and a subsequent failure to properly treat the water to make it less corrosive.

The inaccurate records and falsified reports led Michigan’s attorney general to charge three city and state officials with felony and misdemeanor crimes, including tampering with evidence. They dropped charges against one of them after he cooperated with prosecutors.

Chicago has also been testing homes at lower risk for lead problems. The Chicago Tribune recently reported the testing “likely misses problem areas.”

“The more we look now, the more it seems that water utilities are by-and-large in the dark … about whether the homes they sample, are, in fact, meeting regulatory requirements,” says Lambrinidou, explaining a pattern she’s noticed across the U.S.

The Lead and Copper Rule

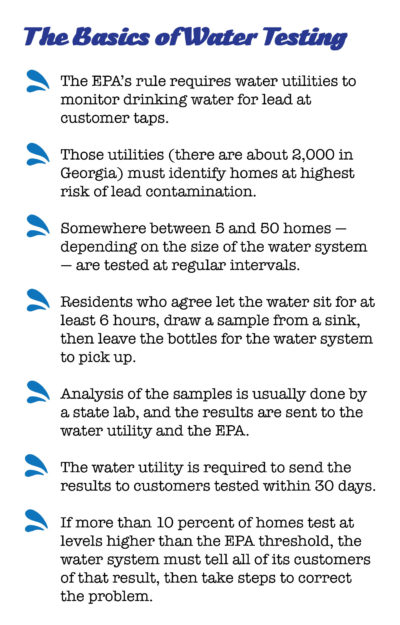

In 1991, the EPA ordered public water systems to begin testing water for lead, a soft metal that’s been a major component of plumbing around the world for generations. (The very word “plumbing” derives from the Latin word for lead.)

Because lead can leach into water as it travels through pipes, operators are required to collect samples from inside homes, usually from a bathroom or kitchen sink.

To make sure the testing works as intended, the rule requires them to test homes most likely to be in harm’s way because they have lead in their plumbing.

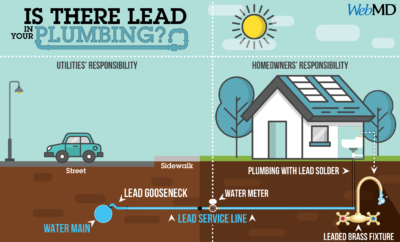

Homes are considered to be at highest risk for lead if they meet one of three conditions:

** They are fed by lead service lines that carry water from the supply in the street to the house; these are typically found in homes built before the 1940s.

** They have lead pipes inside the house.

** They have copper pipes joined by melted lead solder installed between 1983 and 1988, the last year that high amounts of lead were allowed in new plumbing.

Once a water system has identified a large pool of highest-risk homes, they are supposed to test some of them regularly.

Glenn Page, general manager of the Marietta Water Authority in suburban Atlanta, says he remembers how they identified their high-risk homes. In the 1990s, they used kits that included a sharp tool to scrape samples from pipes to verify the metals used in the plumbing.

“I still remember practicing with those kits under the sink in our office break room,” Page says.

Van Collins, assistant director of Water and Wastewater for the City of Statesboro in Southeast Georgia, says his department also works hard to test the same high-risk houses.

“It’s the right thing to do, and also, it’s the law,” Collins says.

That’s not the case in Demorest. The town that tested gas stations, doctors’ offices, and an empty lot also failed to test any of the homes it had originally selected as high risk back in the 1990s. That’s a concern because records show that all those homes had lead service lines.

Charlie McGugan, the city’s director of wastewater, signed the lead testing forms in 2015. He said he didn’t believe any homes in the city ever had lead service lines. He said he thought the homes originally identified as being at highest risk had been mislabeled.

Asked why the original records kept by his predecessors were inaccurate, McGugan said, “Sometimes we get lazy, don’t we?”

He also said he thought the rule required testing a variety of different buildings, not just homes.

He admitted to testing his own home as well as the homes of several water department employees and a city councilmember. That’s not prohibited, as long as their homes are at risk for lead problems. McGugan acknowledged that most of those homes didn’t have the kind of plumbing that would make them eligible test sites.

City Manager Kristi Shead said Demorest would conduct its own investigation and that the testing would be watched more closely going forward.

“Unfortunately somebody made a mistake,” Shead said.

Danny Young, the water system manager for Notla, in North Georgia, explained his decision to test employee homes this way: “We chose homes that it was easy for us to send out the sample bottles.” Young also said he doesn’t believe any of the homes in their district have lead in their plumbing.

Census data, however, show that more than 2,400 residences in Union County were built in the 1980s and could be the right age to have potentially risky plumbing.

Other water utilities said it was difficult to get people to agree to the tests.

Kurt Anthony, general supervisor for the Albany Water System, explained that they tested businesses after some residents declined to participate. He said the state granted permission to do that.

Jac Capp, chief of the Watershed Protection Branch at the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (EPD), confirmed the commercial sites Albany tested are on a list of approved sampling sites. He also noted that lower-risk commercial sites make up about one-quarter of the sites the state has given Albany the OK to test.

We asked Capp why a city the size of Albany, which has more than 77,000 residents and more than 4,000 homes built in the 1980s, should need to have any lower-risk sites in its sampling pool. In a written statement, he said, “The Rule allows the Water System to sample Tier 2 [lower-risk] sites.”

One water policy expert says that’s a very loose interpretation of the law.

“It is difficult to imagine how a utility of any size that has single-family homes older than 1986 can’t find enough highest-risk sites,” says Tom Neltner, an attorney and chemicals policy director for the Environmental Defense Fund.

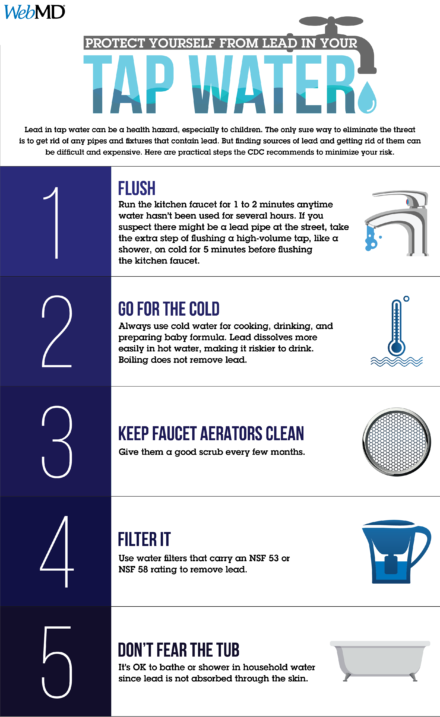

Other water operators around the state and the U.S. also say it is hard to find enough customers who agree to do the testing, which requires residents not to use their water for at least 6 hours, typically overnight. They then fill sample bottles from a kitchen or bathroom tap and leave the bottles for pickup by the water utility.

“You were literally going in the phone book begging people,” says Steve Stubblefield, water treatment operator for Lawrenceville. “It got to be that we’d test a lot of the City Council and city managers and stuff like that.”

Many of those employees’ homes were not at highest risk for lead, Stubblefield admits.

According to Census data, about one-third of 11,000 residences in Lawrenceville were built in the 1980s, making them the right age to potentially qualify as high-risk.

Yet in 2015, water records indicate none of the 30 homes they tested had lead in their plumbing. Property records reveal more than half the sites were built after 1988, the year high amounts of lead were banned from new plumbing.

Customer reluctance is a problem

Other water utilities agree that customer participation is a major barrier to doing the testing correctly.

In Philadelphia, officials estimate the city has 40,000 to 50,000 homes with lead service lines. Still, the city says it can’t get enough people in these homes to participate in lead testing.

“The reasons for low participation are many, and are not exclusive to Philadelphia. Some homeowners don’t want the inconvenience of collecting samples, others fear government intrusion of any sort,” says Mike Dunn, deputy communications director for the city.

Because of problems with low participation, the city last year offered a $50 credit on water bills for people who agreed to test. “We hope this incentive boosts participation levels going forward,” Dunn says.

For its part, the EPA has been meeting with water utilities, lead experts, environmentalists, and regulators in an effort to improve the lead testing process.

Internal emails show those meetings, along with the Flint water crisis, have prompted some soul-searching at the agency.

Brian Smith, an environmental engineer in the EPA’s Region 4 Southeast office, said he has learned two key lessons from those discussions:

First, “The rule alone does not adequately protect public health by preventing exposure to lead in drinking water,” he wrote in a widely distributed email sent on Jan. 28, 2016.

Second, the rule gives the EPA and the states the authority to act in ways that could be more protective to public health, rather than “defaulting to the easiest alternative to implement,” he wrote.

Turning a blind eye to test sites

Since the 2015 Flint water crisis, the EPA has been paying more attention to how states enforce the Lead and Copper Rule.

In an October 2016 memo, the EPA asked its regional offices to be sure that water utilities in their areas were testing sites that were truly high risk and that this information be “well documented.”

The Lead and Copper Rule offers water utilities guidance about ways to identify high-risk homes.

But Lewis Hays, manager of Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division’s Watershed Compliance Program, says in a written statement to us that “there is no specific verification requirement” for choosing lead testing sites. As a result, the state has relied on an honor system, trusting utilities to test homes that qualify under federal rules.

Often, they don’t, and the problem is not new. Emails show state officials talking about it in 2012.

“We have no real way of routinely knowing/verifying what the plumbing material at any of the sites really is … so we just have to ‘trust’ and take the word of the operators/systems reps,” wrote Tamara Frank, an EPD water compliance officer, in an email to a co-worker. As of January, Frank was one of just two state employees who managed the requirements of the rule for more than 2,000 water systems in the state.

When the test finds lead

Every three years, the city of Atlanta tests about 50 homes it considers at high risk for lead. In 2015, the water department asked Allison if she would participate.

When she got her results back, there was a surprise:

Her house was 17 parts per billion for lead, just over the EPA’s limit of 15.

Allison says she got a letter in the mail with the result, but very little guidance about what to do.

“There wasn’t any perspective, really, about what does this mean and how can this affect your health, how dangerous it is and what’s the science behind it,” says Allison, who’s lived in the house for 20 years.

Renee Hepler, who lives in the Atlanta suburb of Roswell, noticed black soot had started to collect in the top of her filtered water pitcher.

She asked her water system to test for lead, and hers was one of 50 homes the North Fulton system tested in 2015. She says she finally got her results, but “I had to stay on top of it.”

“That test basically did show there was lead in our water,” she says. “I was really alarmed, but they said, ‘It’s below the EPA’s action limit, so we’re not required to do anything about it.’ ”

Hepler lives in a house that was built in the 1980s. She has two young children at home. Records show her lead level was 2.5 parts per billion.

“I thought I heard them say, ‘it’s a safe level of lead,’ but I asked my pediatrics office and they said, ‘there’s no safe level.’ ”

The answer to the question of what is safe isn’t easy to come by. No one knows exactly how much lead in water starts to cause harm. The CDC says no amount of lead in blood is safe.

Lead is especially dangerous to children, who absorb as much as 90 percent more lead into their bodies than adults. Researchers have found that even at low levels, lead can damage a child’s brain, lowering intelligence and damaging their ability to control their behavior and attention.

At higher levels, lead can affect growth, and it can replace iron in the blood, leading to anemia and fatigue.

In adults, lead poisoning can cause high blood pressure and damage the nerves and kidneys. It also can cause miscarriages.

The EPA limits, though, are not based on these health risks. Instead, the limit only lets water utilities know whether they’re treating water correctly to minimize harm.

The agency is in the process of setting a “household action level” for health that might trigger intervention. In February, the EPA asked scientists to comment on studies estimating how much lead in water might raise a child’s risk of having elevated lead in their blood.

For babies who are fed formula, the danger level in water could be as low as 4 parts per billion, according to an analysis of the studies by the Environmental Defense Fund.

Kathy, a Roswell resident, lives in a home that tested high for lead in 2016. She says she received a letter so generic, she didn’t even realize there was a problem. Her test result was 21 parts per billion.

“You would think if your home was over the limit that you would get some kind of letter that would warn you about the dangers, but that’s not the kind of letter we got,” says Kathy, who also asked that her last name not be used, to protect her home’s value.

The letter never explicitly states that Kathy’s home tested high for lead. An accompanying report shows her results, and then mentions the EPA’s action level in the fine print.

“We’re not isolated here. All these other houses in our neighborhood were built around the same time. How many other homes have lead in their plumbing, and what’s being done about it?” Kathy says. “People are not being sent to the hospital in droves, so there’s nothing to worry about here? I don’t think so.”

A belated discovery

Allison, in Sandy Springs, ended up calling a plumber. He installed a water filter at the point where the water service line enters her house. She uses a filter on her refrigerator, too. She has a water pitcher with a filter on her counter.

But they took those precautions only last year. Her family has lived in the house for 20 years. Her children grew up there “not knowing a thing,” she says.

Allison’s son is now 22 and though doing well in college, has ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). He grew up in the house where she still lives.

No one can say whether lead in their drinking water played a role in his ADHD, though, because none of her kids ever had a blood test to check, and lead is just one of many things that have been associated with the condition.

In 2015, more than 2,500 preschool-aged children in Georgia had elevated levels of lead in their blood, according to state data, though not all children were tested.

Most of the time, when a child’s test shows high levels, families never find out what caused it.

That’s because the state doesn’t do an investigation until a child’s blood lead level reaches 10 milligrams per deciliter. That’s the standard in other states, too. Only about 1 in 6 kids in Georgia whose tests for lead are high reach that level.

The Georgia Department of Public Health says federal funds for lead programs have been reduced and are restricted to testing and prevention, not investigations. The agency says it is also working on measures to provide guidance and education to families with children whose lead levels fall between 5 and 9.

Children exposed to lead at lower levels often don’t have immediate symptoms, but studies have found that they do suffer from damaged intellects and attention, and that those effects linger for decades.

“What you end up with is many hundreds of thousands or millions of children whose IQ is lower, who are, to use the colloquialism, “more stupid” than they needed to be because of this lead poisoning,” says Jeffrey Griffiths, MD, a professor of public health and community medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston and an expert in waterborne diseases and toxins.

He says while there are plenty of water utilities doing things right, “there are a number of utilities where they haven’t really followed the spirit of the law, and this is what you see.”

Chris Rustin, DrPH, used to oversee lead programs for the Georgia Department of Public Health as its environmental health director. When informed of our results, he said the widespread water testing problems in the state were startling.

Rustin, now a professor at Georgia Southern University, said, “I think now that we know that there’s a potential issue, there’s an opportunity to do something about it.”

COMING TUESDAY: Searching for Georgia’s lead service lines

COMING WEDNESDAY: Her home showed high lead; she wasn’t told

SOURCES:

Yanna Lambrinidou, PhD, anthropologist, civil and environmental engineering department, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA.

Glenn Page, general manager, Cobb County-Marietta Water Authority, Marietta, GA.

Kathy, homeowner with elevated lead in her water, Roswell, GA.

Lewis Hays, manager, Watershed Compliance, Georgia Division of Environmental Protection, Atlanta.

Steve Stubblefield, water treatment operator, Lawrenceville, GA.

Allison, homeowner with elevated lead in her water, Sandy Springs, GA.

Renee Hepler, Roswell, GA.

Chris Rustin, DrPH, assistant professor, environmental health science, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA.

Dawn Harris-Young, press officer, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Atlanta.

Kurt Anthony, general supervisor, water quality, Albany Utility Board, Albany, GA.

Danny Young, system manager, Notla Water Authority, Blairsville, GA.

Van Collins, assistant director of water and wastewater, Statesboro, GA.

Charlie McGugan, superintendent of wastewater, Demorest, GA.

Jeffrey Griffiths, MD, professor of public health and community medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston.

American Journal of Public Health, February 2016.

“Documents show Flint Filed False Reports about Testing Lead in Water,” MLive.com, Nov. 12, 2015.

Water testing records for 118 public water systems in Georgia.

“Charges dismissed against Flint water official,” Detroit News, May 4, 2017.

Kristi Shead, city manager, Demorest, GA.

James Capp, chief, Watershed Protection Branch, Georgia Environmental Protection Division.

Mike Dunn, deputy communications director, Philadelphia.

Brian Smith, environmental engineer, Region 4, Environmental Protection Agency.

Tom Neltner, chemicals policy director, Environmental Defense Fund