Not all fat cells are created equal.

White cells store globs of fat and make bellies jiggle. Brown cells burn fat and keep mice slim.

In between is a type of fat called “beige,” which may be a key to fighting the bulge.

This prospect is so trendy that a beige-fat expert was featured in November during the nation’s largest meeting of obesity experts and bariatric surgeons.

And though “beiging” is not widely studied as yet, it has caught the attention of researchers at the University of Georgia.

Both beige and brown fat cells burn energy and produce heat, Bruce Spiegelman, a professor of cell biology and medicine at Harvard Medical School, said in his

keynote address at Obesity Week 2013 in Atlanta.

But they have different origins, with brown fat arising from muscle cell precursors, and beige fat cells emerging from cushy pools of white fat.

What brown and beige fat cells share is a gene called uncoupling-protein 1 (UCP-1), which gives them the ability to generate heat, said Spiegelman, a professor of cell biology and medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Under normal conditions, beige cells barely express this gene and consume little energy. With the right stimulation, the expression of UCP-1 throttles up the cells, gobble energy and release it as heat.

The hand on the gear shift is a molecule called meteorin-like, which triggers a chain of events in the immune system that activates the beige fat cells in globs of white fat.

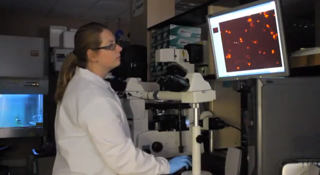

UGA nutrition researcher Clifton Baile and his research group are using phytochemicals to turn immature white fat cells into beige ones. Phytochemicals are naturally occurring chemicals found in plants.

“We want to see not only if we can eliminate [the white fat cells’] filling and development, but to move the cell development more to the beige,” said Baile, who leads UGA’s campus-wide Obesity Initiative.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaZkXDCW3Hk[/youtube]If his lab’s current experiments using rodents are successful, and white fat cells can be redirected without harm to the animals, they hope eventually to try this with human volunteers.

Colette Miller, a Ph.D. student in Baile’s lab, thinks science is headed for the beige.

Researchers from other institutions have been able to jack up heat-producing activity in brown fat cells, but the drugs that made this happen are too dangerous to ever be used as treatments for human obesity.

“I think the beiging is going to probably be a better story,” Miller said.

Phytochemicals are not only safer than those earlier drugs, but these natural plant chemicals also fight bone loss and reduce the symptoms of fatty liver disease.

They even act in other ways to help reduce the number of white fat cells.

The Baile and Spiegelman labs, as well as others, are hoping to develop products that turn on the heat-producing, energy-burning action of fat.

With rates of obesity rising in the United States and much of the world, Spiegelman believes this is a problem that society must solve.

“We must provide multiple avenues of therapy – surgery, medicine and education,” Spiegelman said.

Hyacinth Empinado is a freelance science writer. She is currently a first-year graduate student in the health and medical journalism program at the University of Georgia.