Part 5 of a Special Report

The concept isn’t exactly new.

Free-standing ERs — affiliated with hospitals but not physically connected to them — have cropped up in many areas, generally in suburban or urban locations where large numbers of local residents have private insurance. They provide emergency medical services apart from a regular hospital location.

Now federal health officials are developing plans for something similar, but in a different setting.

“Rural Emergency Hospitals’’ are part of a bipartisan proposal that would replace full-service medical facilities in rural areas with standalone ERs.

An REH would be run independently, with an emergency department and, perhaps in some cases, a few outpatient services. Federal health programs would pay more than standard Medicare rates for services at such a facility.

It’s the basic idea that officials in Cuthbert and Richland envision as a replacement for their shuttered Georgia hospitals.

The proposal isn’t clear whether an already-closed hospital could be converted into an REH. Still, it’s an interesting potential remedy for rural communities struggling to preserve health care.

Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ administrator, said the rural emergency hospital initiative “is a priority for us to implement.”

More insurance coverage

Other ideas – many that have been put into practice — have been promoted to bolster rural health care.

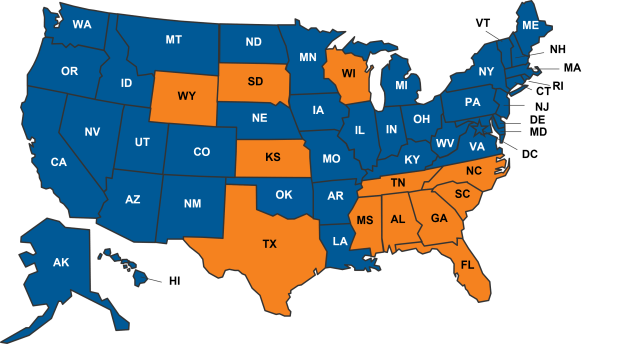

The biggest one is for the 12 states that have long declined to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to agree to do so. Most of these states are in the South, and Georgia is among them. In this state, expansion would mean up to 500,000 low-income uninsured adults would get coverage under the federal-state program. Georgia has the third-highest uninsured rate in the U.S.

Dozens of people associated with rural health care told GHN that Medicaid expansion would be a big help in Georgia. They say it would mean more compensation for providers whose patients have no health insurance or other means to pay. But Republican leaders in Georgia, citing costs, have rejected expansion.

In Congress, an alternative to expansion surfaced in the Democrats’ social-spending bill. It would target low-income people in the 12 non-expansion states who don’t qualify for regular Medicaid but don’t earn enough to get discounts on coverage they buy on the health insurance exchange. Under the plan, those people would qualify for those discounts for four years, starting in January.

The bill’s fate in Congress is unclear.

Filling provider gaps

Among other recommended steps:

Attracting those likely to stay: Katie Metts, a nurse from a small town in Florida, now plans to be a physician. She has started medical school at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (PCOM) campus in Moultrie. When she worked as a nurse practitioner in Jacksonville, she said, “sometimes we’d get patients from South Georgia. They would have complex diseases. A lot of times their outcomes weren’t good. I wondered whether they had good access to health care.’’

PCOM, with the new Moultrie campus, targets students from southwest Georgia in admissions, as well as those with connections to the area, and those interested in practicing in underserved areas.

Aiming to boost the state’s physician workforce, the Mercer University School of Medicine in Macon accepts only Georgia residents as applicants. “We started preferentially looking at people from rural areas. Our hope is that they understand the need,’’ said Dr. Jean Sumner, dean of the school.

One of the recent Mercer grads, Dr. Justin Peterson, an OB/GYN in Douglas in Coffee County, said he wanted to come home to practice because his family is there and “I wanted to give back to the community who raised me.’’

Shorter med school: The Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University is shortening its med school curriculum to three years from four for students who want to work in primary care in rural or underserved areas. “It’s a really good deal,’’ said Scotty Hall, who grew up in the small town of Dexter in Central Georgia. Scholarships are available for tuition as well. Peach State Health Plan, run by Centene, has contributed $5.2 million to the MCG program. Mercer offers a similar shortened curriculum for med students.

Loan repayment programs: A Tifton hospital paid off $100,000 of the medical education loans for Dr. Flavia Rossi, a pediatrician in the town. The terms of the deal required her to work in Tifton for three years, which she fulfilled, but she has stayed there “because I like it. I like the small-town life.’’

Primary care clinics: Mercer has opened four primary care clinics in underserved rural areas, including one in Plains after a request from the town’s most famous resident, former President Jimmy Carter. “Our goal is to go where there’s no care,’’ said Dr. Sumner. Another clinic is planned for Harris County.

Diversified services: Miller County Hospital in southwest Georgia has accepted a stream of patients considered “medically needy,’’ who are eligible for Medicaid through disability, into its nursing home. “No nursing home in the state would take them,’’ said Robin Rau, CEO of the hospital, which also benefits from services delivered to those patients. “We’ve taken 200 to 300.’’

Mobile clinic: Rau of Miller County Hospital runs a medical “truck’’ clinic to nearby counties that have lost their hospitals. It’s equipped for telehealth, EKGs, X-rays and lab work, and is staffed by a nurse.

“I’ve been asked by these communities to help them,’’ Rau said. “I will not reopen their hospitals, I will not staff an ER.’’ But by sending the mobile clinic into areas of need, she said, “I’m willing to lose some money.’’

The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation contributed funding for the reporting of this article.

Read Part 1: A rural Georgia community reels after hospital closes

Read Part 2: How rural health care ‘limps along’ in certain communities

Read Part 3: The ripple effect when rural hospitals drop birthing services

Read Part 4: Gaps in health care hinder some rural areas