Story updated

The devastating impact of the Delta variant helped push John Arthur Brown into action.

Brown, an Atlanta photographer, had been reluctant to get vaccinated. “I was the hesitant one,’’ he said. His doubts were based on how quickly the Covid-19 vaccines were developed.

He had what he called a mild case of Covid last June. But some time later, he began experiencing what he calls long-term Covid symptoms. “Much of it was fatigue,’’ he said.

He recently read a Facebook post that said a person’s long-haul Covid symptoms had subsided after vaccination. With that in mind, and with Delta raging, Brown decided to get the shots in August. And he started feeling significantly better.

Since the introduction of the Covid vaccines early this year, many African-Americans like Brown have been slow to move forward on getting the shots.

But new research and statistics show that the divide between vaccination rates of Whites and African-Americans is narrowing.

The Kaiser Family Foundation, using CDC data, found that vaccination rates among Blacks had risen to 46 percent, vs. 54 percent of Whites, by early October. That gap had once been much wider — 29 percent to 43 percent — in May.

Another newly released analysis also found that the vaccination rate for Black Americans is catching up to the rates for Whites.

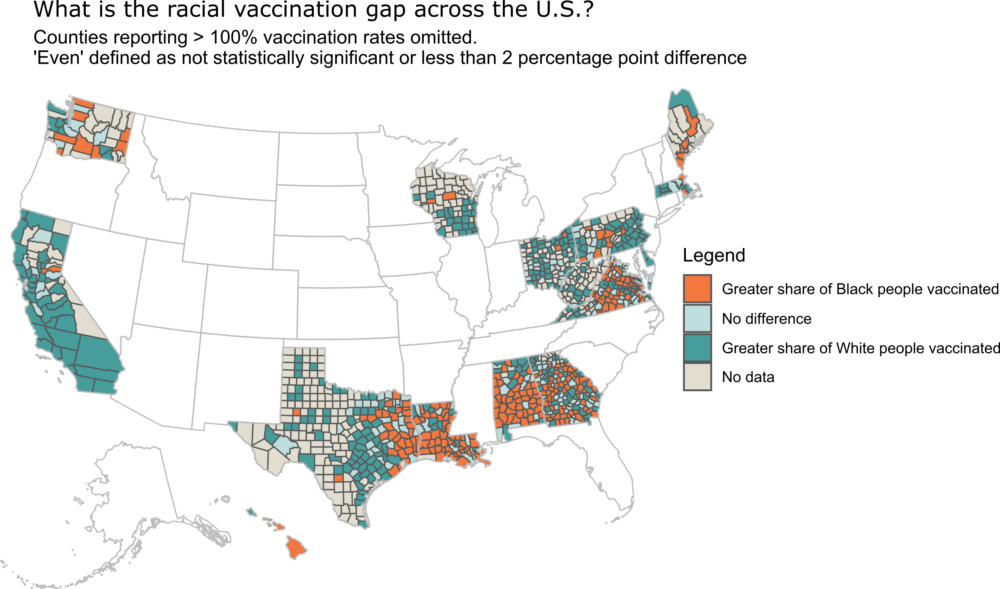

Nonprofit organizations Surgo Ventures and Covid Act Now studied about 700 counties in the U.S. that had data that would show racial comparisons of vaccinations. The analysis found the vaccine gap between the races is narrowing in 94 percent of the counties studied since the end of May.

And in 36 percent of those counties, the Black community has surpassed the White community in vaccination rates. Most of those counties are in rural areas, including the South.

In many counties where Black rates are higher, the overall vaccination rates remain low. And the Covid-related medical outcomes there are worse.

“Across the South, overall vaccination rates are being dragged down by a large percentage of unvaccinated White adults,’’ said Igor Kofman of Covid Act Now.

Black communities, meanwhile have seen “grassroots movements over the summer that engaged community leaders,’’ said Nick Stewart, a senior research scientist with Surgo Ventures.

Current state figures in Georgia show that 44.8 percent of Blacks are vaccinated for Covid, versus 47.4 percent of Whites.

Grim historical issues

Vaccine hesitancy, of course, exists to some degree among all demographic groups. But vaccine skepticism and a general distrust of medical care have historically been issues among African-Americans.

The Tuskegee study is one of the most horrific historical examples that still loom large in the Black community. Under that experiment, which began in the days of Jim Crow, 600 African-American sharecroppers were enrolled in a long-term study to observe the course of untreated syphilis. Participants were told they were receiving free medical care from the federal government, while the actual treatment they needed to stem the progress of the disease was withheld.

Current disparities in the health care system also drive mistrust of medical care among Black Americans, experts told GHN earlier this year.

Building trust has been an ongoing challenge during the pandemic.

“Covid-19 has amplified already existing inequities,’’ said Dr. Patrice Harris, an Atlanta psychiatrist and the first African-American woman to be president of the American Medical Association. “Communities of color have been hit particularly hard by this pandemic,’’ she told a Georgia House study committee recently.

A year ago – before the Covid vaccine became available — a USA Today analysis showed that of the 10 counties in the nation with the highest death rates from COVID-19, five were in Georgia. Hancock County was No. 1 on the list.

The analysis found that many counties with the highest COVID death rates nationally have populations with a majority of people of color. In Hancock County, three in four residents are in that demographic.

Dr. Dominic Mack of Morehouse School of Medicine told the House study committee that Black people in the United States have died of Covid at a rate that 1.4 times that of Whites. Overall cases and hospitalizations among blacks are higher as well.

No simple strategy

Improving vaccination rates “is not a one-size-fits-all’’ fix, said Dr. Cecil Bennett, a Black physician in suburban Atlanta.

“It takes multiple tools in the box to build a house; it will take multiple tools to reach this community,’’ Bennett said.

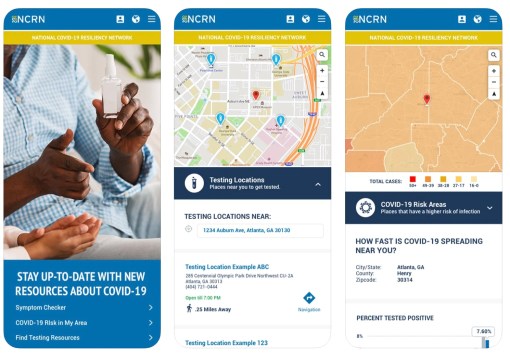

Developing one tool is the National COVID-19 Resiliency Network (NCRN), based at Atlanta’s Morehouse School of Medicine. It has launched a mobile app designed to enable racial/ethnic minority groups to easily access information and health services to help curb the impact of the disease in their local communities.

The app allows users nationally to find nearby vaccination sites and testing facilities, check the prevalence and local spread of the disease, and find nearby organizations that provide services and assistance for people affected by the pandemic.

“The hope is to develop a sustainable model that helps these communities beyond Covid,’’ said Dr. Mack of Morehouse, who is director of the NCRN.

And researchers at Georgia State University are using a $500,000 grant to try to increase vaccination rates among refugees and other groups in the metro Atlanta city of Clarkston, which has one of the largest refugee resettlement communities in the nation, whose members are largely African, Asian or Middle Eastern. The initiative has worked well: Georgia State’s Michael Eriksen said this week that Clarkston census tracts increased their fully vaccinated rate from under one-third (32.9%) in June to over one-half (50.9%) in October.

Bennett also said that “an army of social media stars’’ can reach many young Black adults who have not been vaccinated.

That’s happened recently, both here and nationally.

Pro Football Hall of Famer Champ Bailey, a former University of Georgia star, told a vaccination event in his hometown of Folkston that “we came down here to inspire people and I feel like we’re going leave with inspired people.”

In DeKalb County, a vaccine event at the Mall of Stonecrest in September drew more than 2,500 people, each of whom got a $100 gift card and the chance to meet Atlanta Hawks legends Dominique Wilkins and Dikembe Mutombo. And this month, county officials say, more than 2,100 more residents came out to get vaccinated, get the gift card and meet actor/comedian Chris Tucker and gospel singer Dottie Peoples.

A lot of things can get in the way

The reasons why some Blacks may not get vaccinated have nothing to do with mistrust of the medical system. Sometimes there are personal or practical issues that deter people.

Betty Baugh, 63, is “scared of needles.” But when she recently arrived at a Cobb County community center and saw that Wellstar Health System was holding a pop-up vaccine clinic, she decided to confront her fears. Though she “stalled a little bit,’’ she finally went ahead with the vaccination. Now she has started encouraging her family members to get their shots.

Michael Langley, 69, of Roswell has a mobility challenge: He uses a wheelchair. “Due to physical limitations, I wasn’t able physically’’ to get to a vaccination site, Langley said.

But thanks to another Wellstar pop-up vaccine clinic nearby, Langley was able to get the shots.

Other factors may be driving the recent vaccination momentum for Blacks.

Carey Simmons of Albany faces a mandate from his employer, Procter & Gamble. Simmons, a forklift operator, said that if he remains unvaccinated, he will face Covid testing three times a week – and he will have to pay for the tests. So he’s not going to wait any longer.

“I knew I was going to do it,’’ said Simmons, who has a vaccination scheduled. “That helped me make up my mind.”

Freelance health journalist Rebecca Grapevine contributed to this article.