This article first appeared in STAT, which gave Georgia Health News permission to republish it. Photos are by Bethany Mollenkof for STAT.

By Olivia Goldhill

In every corner of Latasha Taylor’s home are plants she knows nothing about. After years spent shirking her mother’s calls to join her in the yard at sunrise, Taylor now waters them out of duty.

When her mom, Kat, was dying of COVID-19, she would ask about her flowers whenever she was conscious. Taylor promised to look after them.

Now, as Taylor does the work, her late mother seems to keep a watchful eye from framed photos on the wall, dressed like the Queen of England in wide-brimmed hats and matching dresses.

Taylor’s mom, 62, was the third member of her family to die of COVID-19; the virus also took her aunt and uncle. Friends tell Taylor she’s strong, but she doesn’t feel that way. “If you had to, you would do what I did,” she said. “Bury your whole family.”

The family tragedy was only made worse by institutional failings: All three relatives ended up in different hospitals scattered across southwest Georgia. Early in the pandemic, the hospital nearest Taylor’s house stopped accepting COVID-19 patients, and then, in the middle of the worst public health crisis this century, it shut for good.

A larger hospital managed by the same group, Phoebe Putney Health System, received $89.7 million from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ provider relief fund during the pandemic. But the company said it was unable to develop a financial plan for its more rural location, which needed $10 million to upgrade and renovate the facility.

Without a hospital remaining nearby, several residents said their loved ones delayed getting care when they fell ill with what they thought might be COVID. They lacked an easy place to go for rapid tests, missing out on crucial early diagnoses. And, with the next closest hospital overwhelmed, many were forced to drive more than an hour to seek treatment. Taylor’s mother stayed at home for several days, questioning if her symptoms were bad enough to warrant a trip to the hospital. If there had been good care available nearby, said Taylor, she would have gone in sooner.

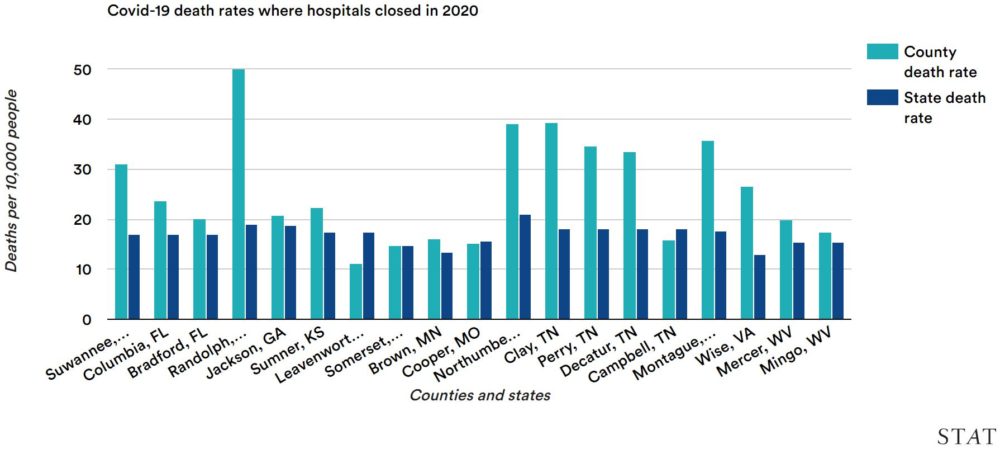

While it’s not possible to draw a direct line from the closing of the hospital in Cuthbert to the Taylor family’s losses, this much is clear: In the two counties, Randolph and Terrell, that depended on the hospital, one in every 200 people has died from COVID-19, a death rate 2.8 times higher than in Georgia as a whole.

The abrupt withdrawal of care that affected this rural corner of Georgia has played out across America. A record 19 U.S. rural hospitals closed in 2020, according to research from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Communities close to these shuttered hospitals similarly experienced disproportionate fatalities, according to a STAT analysis: COVID-19 death rates in counties where hospitals closed were 37% higher than in their states overall.

Looking at the most rural counties — those with fewer than 50,000 residents and at least 50 miles from a major city — the death rates were 66% higher than in their states as a whole. Of the eight hospital closures in counties where the fatality rate was at least 80% higher than the state’s rate, seven were in such highly rural counties.

COVID-19 often requires prompt medical attention, and the closure of hospitals can be deadly. “You’re losing the ability to hospitalize locally and quickly,” said Mark Holmes, professor of health policy at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Like the southwest Georgia community of Dawson, where Taylor, 42, lives, the communities affected when rural hospitals closed often have significant Black populations. “At every step in the pipeline, hospitals with a larger footprint in the African-American community are more likely to shut,” said Holmes.

The closures are predominantly clustered across the South and Southeast where, more than a half-century after longstanding racial segregation in health care was outlawed, plenty of hospitals outside Black communities have yet to earn the trust of African-American patients, erecting another barrier to care.

For Taylor, the lack of a strong local hospital in the pandemic was dismaying. Banned from visiting her mom in a hospital 65 miles away, she had to talk to doctors on the phone as they spoke of amputating her mother’s limbs.

“I hate that it closed,” she said of the Cuthbert hospital. “That doesn’t make a lot of sense. Why would you close a hospital in the middle of a pandemic?”

An essential hospital

Cuthbert, the Randolph County seat, is built around its hospital. A small cluster of streets make up the heart of this city of 3,500, and each street winds its way to Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center (SGRMC). Within minutes of driving into Cuthbert, you inevitably arrive at the hospital’s door, now flanked by a large sign.

“Hospital closed,” it reads in red. “In case of emergency, call 911.”

The one-story, red brick hospital officially shut in October 2020 but already had been out of action for much of the year. At the start of the pandemic, the only two doctors permanently based at the hospital were away for medical reasons, said John Chitoh, a nurse practitioner who worked there for a decade. Phoebe Putney Health System, which managed SGRMC, declared that it couldn’t accept COVID-19 patients. Instead, said Chitoh, every patient from the county would be sent to Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital, 44 miles away in Albany.

That decision was not unusual early in the pandemic, said Holmes, noting that other medical systems also bundled patients at centers with better technology. “It took time to realize that a lot of COVID patients could be managed at many kinds of hospitals, not just the most advanced,” he said. “In March we were still coming to grips with what we were facing.”

Phoebe Putney Health System said in a statement to STAT that the hospital “had neither the staff nor resources to provide the necessary level of care for COVID-19 patients who could decompensate quickly and require immediate transfer to a critical care unit.” Spokesperson Ben Roberts wrote that the hospital lacked ICUs and “24/7 in-house physicians, and transfer to a hospital with those capabilities would take at least an hour in the best of circumstances. The hospital was concerned about patient safety in the face of a devastating disease, not what revenue they might generate from admitting these patients.”

The lack of patients didn’t help the hospital’s finances, which were already troubled before the pandemic. “From a medical standpoint, I can’t understand. They didn’t want us to treat any patients here,” said Chitoh, his eyes incredulous above his mask. “At a certain point, I was looking at nurses sitting there, with no patients. How does a hospital work when there are nurses there, but no patients?”

The hospital’s management didn’t even allow it to offer COVID-19 tests to residents from the community, Chitoh said. It had a full lab, which was used only to process tests from the nursing home next door. SGRMC staff had to go to the nursing home to get the tests that would be analyzed at their own hospital. “I was dumbfounded,” said Chitoh.

After months of turning away patients, Phoebe Putney Health System said it would need $10 million to save the hospital. “SGRMC had been operating on the brink for years and before the COVID-19 crisis, we had not been able to finalize a workable plan to ensure the hospital’s future success,” said hospital chief executive Kim Gilman in July. “Once the crisis hit, it simply pushed our hospital past the point of no return.”

By contrast, the Albany hospital that received $89.7 million in government funds fared much better during the pandemic. In June 2020, Moody’s revised its financial outlook from negative to stable. “We have spared no expense to ensure our caregivers have all the necessary resources and personal protective equipment required to safely provide care to our COVID-19 patients, and we have not laid off or furloughed a single employee,” said Brian Church, the chief financial officer of Phoebe Putney Health System.

Although Phoebe Putney manages SGRMC, the Cuthbert hospital is owned by the county. The Cuthbert hospital received $4.1 million in HHS provider relief funds last year, but this was not enough. And so the Randolph County Hospital Authority agreed to close it with Phoebe Putney’s support.

A 2020 study by the health care consultant Guidehouse, which examined hospitals at high financial risk of closing, listed SGRMC as one of five essential hospitals in Georgia. Factors including the jobs and charity care provided, and how far residents would have to travel to the next nearest hospital, meant SGRMC was too valuable to lose.

Since it closed, there’s no doctor practicing in Cuthbert for the first time in more than a century. In 1916, the city’s first hospital was built by Frederick Davis Patterson, a physician who always wore a flower — typically a red one — in the lapel of his coat. Patterson Hospital grew into several different buildings, and changed its name to Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center in 1994, though many locals still refer to it by the old name.

A community health center sits next to the shuttered hospital, where Chitoh has taken on many of the medical needs of the city. The primary care clinic’s website advertises itself as a cost-effective alternative to an emergency room, though there’s no doctor on staff. Chitoh has his own office, and manages his patients’ concerns much like a family physician. He worked in the hospital for a decade, and has no plans to leave. Born in a small community in the West African nation of Cameroon, he said he likes being part of this close-knit town in Georgia.

The closest emergency care now requires a 25-mile trip to a hospital in Alabama, but crossing the state line can create Medicaid and insurance complications. Many patients face reduced coverage when getting care outside Georgia, said Holmes, and they may not find out the full details of what they owe until months after receiving care. Fear of these future bills deters patients from seeking care across state lines.

This issue is a huge concern for rural areas across the country, said Alan Morgan, chief executive of the National Rural Health Association. “You may only be 10 or 15 miles to the nearest hospital, but it’s across state lines so that creates a barrier to access,” he said.

As a result, most Randolph County residents go to the Albany hospital, roughly an hour’s drive from Cuthbert. For those without cars, the distance is a huge deterrent. And if anyone calls 911, as the sign outside the hospital advises, there’s only one ambulance in the county. Every time someone has to be taken to the hospital, the county is left without an ambulance for three hours, as the paramedics drop the patient off and deal with paperwork before returning.

The road from Cuthbert to Albany is flanked by acres of peanut and cotton plants, growing in Georgia’s red clay. The route winds through Terrell County, which lost its own hospital decades ago, and where the long, low building still sits unused, with broken windows and chandeliers thick with dust.

Difficult decisions

The area has survived plagues before. In 1864, when Georgia became a major battle front in the Civil War, a terrible smallpox outbreak spread through Cuthbert. “If you doubt me, just go down to Greenwood Cemetery and take a look,” wrote C. W. Cobb, one of the doctors at the time. The smallpox deaths were easy to spot, he said, “because the graves of those dying of a contagious disease had to be marked.” COVID has brought fresh graves and misery.

As Taylor’s relatives died one by one, she was forced to make agonizing decisions about how they would be cared for. Her aunt and uncle got sick first, in late March 2020. Her cousin didn’t trust the Albany hospital, which was overcrowded, and so he drove his parents over an hour to Columbus. One was transferred to Macon and the other to Tifton, 100 miles and a 90-minute drive apart.

A few days later, Taylor’s mother called, saying she had a fever that wouldn’t go down. Taylor tried to persuade her mom to seek treatment, but she refused. Taylor thinks her decision might have been different if she’d had confidence in the struggling Cuthbert hospital. “Knowing that [the fever] was one of the main symptoms of COVID-19, I think she would’ve gone to the hospital immediately,” she said. “Her thinking ‘they’re not going to care for me the way I need to be cared for’ is the reason she held off.”

Not long after, Taylor’s mother was coughing uncontrollably and struggling to breathe. Taylor, who was at work in Columbus, called an ambulance, but the paramedics wanted to take her mother to the Albany hospital. Taylor said no. She’d heard about negative experiences from other patients, so she asked her cousin to drive Kat 65 miles to St. Francis Hospital in Columbus.

She was there for months, often on a ventilator, and was unconscious when Taylor’s aunt and uncle died in April. When she awoke temporarily in May, she immediately asked how her sister was doing. “We just cried together,” Taylor said.

Shortly before her mother died, the doctors said they would need to amputate her hands and her legs from the knees down.

“Because she wasn’t able to be mobile, her body started to deteriorate,” said Taylor. “Her blood wasn’t circulating to those extremities. They were just rotting.”

Kat was always sociable, went to church on Sundays dressed in glamorous dresses, liked digging in the yard every hour of daylight, and Taylor knew she wouldn’t want to live in a nursing home without her limbs. The only alternative, the doctors said, was to let her mother die peacefully. She wasn’t conscious, but Taylor knew she had to tell her in person.

On June 5, 2020, she went to visit Kat. “I told her everything I wanted to say to her,” Taylor said. “Even though she wasn’t responsive, I know she heard what I said because she started to cry.” Three days later, Taylor gave the doctors permission to withdraw the ventilator.

Others who lost relatives also wonder whether a strong local hospital would have made a difference.

Paul Langford, the mayor of Shellman in Randolph County, said the lack of readily available COVID-19 testing in Cuthbert delayed diagnosis for his 73-year-old sister, Mary Jane Salter. She got her first vaccine dose in February 2021, but contracted the virus at a bridge game less than a week later, before protective antibodies had time to kick in.

“I think if it had been diagnosed earlier, it would have made a difference in when they gave her the COVID-19 antibodies,” he said, referring to therapies that can prevent serious disease when given early. One of his sister’s friends with several underlying conditions contracted the virus at the same bridge game but received antibody treatment sooner and was able to recover, Langford said.

Salter died at the hospital in Albany, with her daughters at her side. On their drive home, as they neared Shellman, their vehicle was rear-ended. The car flipped over, and one daughter had to be flown by helicopter to Dothan, Ala., and another was taken by ambulance back to Albany. While the two were recovering in separate hospitals, Langford was left to plan his sister’s funeral.

Racial divides

The history of racism in Randolph County is far from hidden. In the center of Cuthbert, outside Andrew College, is a historical marker honoring the school’s namesake. “Named in honor of Bishop James O. Andrew whose refusal to free his Wife’s slaves separated the Northern and Southern Methodist Episcopal Churches (1844.),” it reads in gold font.

Racism today is less overt in the county, though it remains a place of stark inequality, where antebellum houses, complete with columns and manicured gardens, sit yards from squat public housing bungalows. Randolph has a median per capita income of $16,691, with one-quarter of the population living in poverty, most of them Black.

Many residents can’t afford a car. Getting to and from the hospital is a common concern, and Randolph County’s only ambulance often helped patients out after they were discharged from the Cuthbert hospital. “They were sometimes a taxi service. If a patient didn’t have a ride home, they were excellent at helping them,” said Sherri Cartwright, former head of nursing at the hospital. “Which they weren’t supposed to, but they did.”

Racial divides are still prevalent, even after death. Danny Pearson, from Lunsford Funeral Home in Cuthbert, said his clients are overwhelmingly white, though he’s worked with some African-American families. The burial customs tend to be different, he explained, and the dozen or so COVID-19 funerals his company organized were all for white people.

Just over a mile away, Perkins Funeral Home serves mostly African-American families. Thomas Bailey said he has buried around 40 to 50 people who died of COVID-19. The demise of the local hospital was a blow in the middle of so much tragedy, said Bailey. “Every community needs a hospital.”

Cuthbert’s hospital was so essential in part because it was historically more welcoming to Black patients, said Robert Albritten from Albritten’s Funeral Service in Dawson, in Terrell County. “In my youth, the hospital known as Patterson hospital provided the service for Blacks in this immediate area for about 30 miles,” he said. From the ’40s to the early ’60s, Black people couldn’t give birth at the Terrell County hospital, added Albritten, a former mayor of Dawson and the first Black city councilman elected there, in 1991. “Hospitals in this area were less friendly to Blacks.”

Dawson is midway between Albany and Cuthbert, and so people living in the county still have a hospital fairly near. But Albritten said many preferred to go to the Cuthbert hospital, which is slightly closer, precisely because of its historical openness toward Black people. “The one in Albany was lukewarm,” he said. “They were not that receptive. You got better treatment at the Patterson hospital.”

CARES help

As difficult as the past year was for rural hospitals, experts fear worse is to come. The same forces that precipitated the shutdown of Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center — declining health in large swaths of the country and population decline — are decimating other rural hospitals.

Several potential hospital closures were averted last year thanks to federal relief funds included in bills such as the CARES Act. Once that short-term aid dries up, the economic conditions have not changed.

“The populations that these rural hospitals serve are a sicker population and in many cases a lower-income population,” said Morgan of the National Rural Health Association. Failing to provide proper care only escalates costs in the long run. “The data shows there’s a race factor here.”

Passage of the Affordable Care Act more than a decade ago was a boon to many hospitals because it slashed the number of uninsured, but many states refused to expand Medicaid, and it is these states — including Texas, Tennessee, and Georgia — that are home to the majority of hospitals that are at risk of closing.

In Randolph County, jobs have been dwindling for years, leading many residents to move away. Cartwright, the former head nurse who worked at the hospital for decades, said patient numbers steadily declined. In the ’80s, there would usually be around 25 admitted patients in the hospital. More recently, seven inpatients was standard, she said, with around 20 coming to the emergency room daily. Staff were also in short supply. It was often hard to get nurses to stay and work at the hospital long-term, said the nurse practitioner Chitoh, as people would complain they didn’t have a life.

When SGRMC closed, more than 50 jobs also were lost. Though some workers were hired by the nursing home, many others have left for good.

Rural hospitals are usually among the top two local employers, said Holmes. Once a hospital closes, retirees often decide it’s not safe for them to stay in the community, while young families, knowing they’ll need pediatric care, also move away. “It does have this real spiral effect,” he said.

This pattern is already playing out in Randolph. Langford said he knows a couple from his church who left the area. “The husband had a couple of heart attacks. They said, ‘I’m sorry, we’ve got to move somewhere closer to a medical facility.’ So we lost them.”

There are still more than 15,500 people living in Randolph and Terrell. Neither county has a place to go when a resident has a heart attack, or gives birth, or get stricken with an unfamiliar virus. And the COVID-19 is pandemic is not yet over.

“It’s scary,” said Langford. “People are going to die.”

Olivia Goldhill is an investigative reporter at STAT.

Bethany Mollenkof, a visiting Nieman Fellow for STAT, contributed reporting. This story has been updated with comments from Phoebe Putney Health System.