By Brenda Goodman and Andy Miller

Brenda Goodman is a reporter for Medscape and WebMD. Andy Miller the editor and CEO of Georgia Health News.

On August 22, 2018, the citizens of Willowbrook, Ill., had just one hour to learn that local EPA officials were investigating high levels of a toxic gas in the neighborhoods near their homes.

Then those officials, who were staffers in the EPA’s Region 5 office, got a call from their bosses in D.C. with an order: Take down the webpage on the investigation.

When the page was eventually reposted, key parts had been removed, including important context about a facility run by the company Sterigenics that used the chemical ethylene oxide to sterilize disposable medical equipment and other goods.

Also removed were details about the extent of the EPA’s involvement in the investigation, and crucially, a statement that the EPA had determined that ethylene oxide could cause cancer.

Top officials in the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation in Washington, D.C., further directed all regional offices not to test the outdoor air around facilities that use ethylene oxide anywhere else in the country.

“The instruction to limit ambient air monitoring for ethylene oxide to the Sterigenics facility in Willowbrook, Illinois, applied to all EPA regions,” said Jennifer Kaplan, deputy assistant inspector general in the EPA’s Office of the Inspector General, by email. “No other ambient air monitoring of ethylene oxide-emitting facilities was permitted,” she said.

Last week, a report by the EPA’s Office of the Inspector General, an independent watchdog that oversees the actions of the federal agency, said “political appointees” hindered the efforts of agency staff to investigate the scope of ethylene oxide contamination.

In the new report, the OIG details for the first time the extent of senior officials’ role in the environmental crisis in Willowbrook and touches on how policies triggered by that investigation affected other areas, including metro Atlanta.

An EPA office in a pollution hotspot

The Sterigenics facility was centrally located in Willowbrook, a suburb of Chicago. The facility sat one block north of the Village Hall and the police station and within half a mile of the nearest homes and three schools.

It also happened to be just down the street from an EPA warehouse that stored equipment used at Superfund sites.

After staffers working in the warehouse saw an early draft of an EPA air report showing elevated cancer risks from ethylene oxide, they probed further, first modeling the risk and then testing the outdoor air over two days in May 2018.

The ethylene oxide levels they found were alarming. In some canisters placed closest to Sterigenics, air testing revealed amounts that ranged from .1 to 9 micrograms per cubic meter of air. The highest amount detected was 450 times higher than a federal threshold of concern for the chemical, which is .02 micrograms per cubic meter of air, and about 10 times higher than Region 5’s initial modeling had predicted they should be.

They sent their modeling and air test results to another federal agency that often works in close collaboration with the EPA, a specialized division of the CDC that evaluates health risks from known chemical exposures.

When the air test results came back, EPA employees showed them to their bosses in Region 5, and were directed to prepare a press release and background materials for the public “to avoid another public health emergency like the Flint, Michigan drinking water crisis.”

Region 5 leadership briefed top officials in the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation, based in Washington, D.C.

Those officials then directed all regional offices not to test the outdoor air around facilities that use ethylene oxide. The directions to block additional air monitoring and to revise the webpage came from top officials — all appointed by President Donald Trump — in the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation.

The same officials were actively overseeing rollbacks of air quality standards for pollutants like ozone and particulate matter, and would, before the end of their tenures at the agency, would gut tough new rules to regulate carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants.

One of those officials was Bill Wehrum, a former lobbyist for the fossil fuels industry who resigned in 2019 amid an ethics investigation. According to Politico, Wehrum carried out an agenda set by his former industry clients while serving in his post as top enforcer of the nation’s air quality laws.

Another official referred to in the OIG report was his deputy, Clint Woods, who is now a policy fellow for the libertarian conservative advocacy organization Americans for Prosperity, created by Charles and David Koch, frequent foes of environmental legislation.

The 37-page OIG report details for the first time how Washington officials tied the hands of EPA regional staff who were trying to investigate the findings of the 2018 National Air Toxics Assessment, or NATA.

The report says Region 5 managers were directed by the assistant administrator, Wehrum, to delay releasing the air testing results for another two months so the agency could publish full data from the NATA.

The NATA is an extensive look at health risks posed by the release of toxic chemicals into outdoor air. The EPA publishes the report ever four years.

In 2018, for the first time, the NATA revealed elevated cancer risks from toxic gases in 17 metro areas around the U.S. that were above a threshold of concern set by the EPA, including Atlanta. Most of the risk was driven by a single chemical —ethylene oxide.

Ethylene oxide is a colorless, odorless gas that is used to disinfect about half of all the sterile, disposable medical equipment used in the United States each year, according to the Ethylene Oxide Sterilization Association. Companies also use it to sterilize consumer products, spices and cosmetics.

Most Americans had never heard of ethylene oxide until the release of the 2018 NATA and events unfolded in Willowbrook.

Many impacted communities still have not been alerted to their risk from the gas.

Sterigenics, through a spokesman, declined to comment Monday on the Inspector General report. Wehrum could not be reached for comment Monday.

Communities got little help from EPA

In public meetings in affected communities in Georgia, EPA officials from the local Region 4 office described the NATA as a 30,000-foot view of pollution and risk that then demanded more detailed and refined modeling to assess risk closer to the ground.

Emails obtained under a Georgia Open Records Act request show that in the months after the release of NATA, Georgia’s environmental regulators worked quietly with sterilizing companies to refine the amounts of ethylene oxide they reported releasing. They never alerted the public to their work and did not address the risk to metro Atlanta communities outlined by the NATA report until reporters broke the story.

At least one other state, Colorado, was more transparent, issuing a press release about their NATA results the day the report came out.

The estimated amounts of ethylene oxide that Georgia used in its models were much lower than the levels the companies had initially reported to the EPA, which were used in the NATA.

Georgia used those new lower amounts in its modeling, and concluded that the census tracts flagged by the NATA weren’t problems after all.

Karen Hays, who leads the Air Protection Branch for the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, told members of the public at an August 2019 community meeting about ethylene oxide that the EPA had reviewed the state’s models and determined the risk to residents—according to Clean Air Act criteria—was “within acceptable limits.”

When asked by WebMD and Georgia Health News in a June 2019 interview if the state planned to measure actual levels of the chemical in outdoor air through testing, Hays said, “We don’t have the capability at this time,” though the EPA had already done such testing in Willowbrook. Hays said, speaking of the EPA, “they’ve made no indication that they are going to do any testing in Georgia.”

Limiting investigations

The role of senior officials went beyond delaying the public release of the air testing results in Willowbrook.

The Inspector General report details how Wehrum and his staff further tied the hands of regional officials as they sought to get more information on ethylene oxide pollution and its risks to the people who lived around facilities that use the chemical.

The OIG’s report says EPA officials in Washington also denied a request by their Chicago office to compel Sterigenics to release detailed and specific information on their operations, by using a legal lever in the Clean Air Act called a Section 114 letter. The office needed a 114 letter because Sterigencs had stopped communicating with them, according to the report.

It also says “political appointees” directed EPA officials not to seek the help of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), the CDC agency that estimates health risks from chemical invited by state environmental regulators.

When the Region 5 office reposted its webpage on the Sterigenics information in October 2018, key information had been removed. All that was left was a link to the air testing results and the ATSDR report.

The ATSDR report on Willowbrook estimated that the cancer risks to residents of the neighborhoods due west of the Sterigenics site were more than 60 times higher than the federal threshold after 33 years of exposure. The levels detected in the May 2018 modeling predicted an additional 6,400 cases per million people exposed for that long. After just two years of exposure to the highest levels detected in the neighborhoods closest to the plant, toddlers had risks that were 16 times higher than the federal level of concern. The EPA considers cancer risks from air pollution to be unacceptable when they rise above 100 additional cases of cancer for every million people exposed over the course of their lifetimes.

The ATSDR report posted on Aug 21, 2018. The EPA posted the results of its NATA report the next day.

Emails obtained under a Georgia Open Records Act Request show federal EPA officials decided not to issue a press release on the 2018 NATA, though the agency had alerted the press to some previous versions of the same report.

After ATSDR issued its report on Willowbrook, the information was posted on the town’s website and exploded on social media.

Within days, furious residents had organized a nonprofit called Citizens 4 Clean Air and a Facebook group — Stop Sterigenics — to fight the pollution. The group applied constant pressure on state and local officials as well as on the company itself. In September 2019, Sterigenics made the surprise announcement that it would close its Willowbrook location after its landlord refused to renew the lease.

The new OIG report flies in the face of EPA’s public communications about its role in the Willowbrook investigation and the ethylene oxide crisis.

At a public meeting in 2019, Margie Donnell, an attorney who helped organize Stop Sterigenics, asked Cathy Stepp, the head of the Region 5 office, whether anyone had directed her office “not to inspect . . . any companies that emit ethylene oxide in Region 5.” Bill Wehrum was sitting with her on the stage as she asked the question.

“100% untrue,” Stepp said, and further stated that neither she, her air director nor anyone else in her office had ordered that. She went on to say that the Inspector General was looking into that question, but added, “There’s absolutely no foundation to it.”

According to E&E News, which covers energy and the environment, Stepp left the EPA in January 2020.

An EPA spokesperson said this week in a statement that “under Administrator Michael S. Regan’s leadership, EPA has a renewed commitment to protecting human health and the environment by following science, enforcing environmental laws and engaging with communities as we do our work. The agency looks forward to productive conversations with the Office of the Inspector General as we work to resolve this matter.”

New science, old regulations

In 2016, the EPA finished a 2-decade scientific review of ethylene oxide, concluding that it could cause breast and blood cancers in people who were exposed to tiny amounts over a long time. That review was the first recognition by the agency that ethylene oxide gas might be a risk to people who breathed it in outdoor air while living or working near chemical manufacturers and sterilization facilities legally permitted to release the gas.

In 2018, data modelers applied the new science on ethylene oxide to a periodic review of the health hazards posed by toxic chemicals released to air — the NATA report.

The report showed 109 census tracts across the nation where levels of toxic gases released to outdoor air increased residents’ cancer risks above a threshold of concern.

Those findings failed to trigger any additional action by the agency to remedy that risk. (The agency is currently reviewing its regulations on ethylene oxide to see if emission limits should be lowered in light of the new science.)

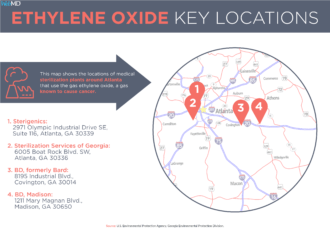

Three of the NATA-flagged census tracts were in metro Atlanta, located near facilities run by Sterigenics, BD, and Sterilization Services of Georgia, that use tons of ethylene oxide gas every year to sterilize medical products.

Another group of those census tracts was in the Chicago suburbs.

WebMD and Georgia Health News exposed the Georgia hotspots for ethylene oxide in July 2019. The story prompted local communities to join together to pay for their own air testing. The results of those air measurements and a Cobb County investigation slowed operations at two of the three area sterilizing plants for a time.

Those restrictions were later lifted amid the push for sterilized medical products during the COVID-19 pandemic. Operations at sterilizing facilities resumed, and new air testing showed ethylene oxide levels had again increased at a Sterigenics plant in south Cobb County.

In addition, regulators have found warehouses where sterilized and stored products are off-gassing (emitting) ethylene oxide at levels high enough to require them to need air pollution permits from the state. These warehouses have lacked any pollution controls for the chemical.

The Georgia Legislature passed a law in 2020 requiring any company that emits ethylene oxide to report all accidental releases of the gas, not just those exceeding a certain threshold. Residents living around the facilities, who have seen their property values drop, say the state and the EPA haven’t done enough.

From the time the ethylene oxide issue surfaced until the reopening of the Sterigenics plant, “we knew the federal government was not on our side,” said state Rep. Erick Allen, a Smyrna Democrat who lives near the Sterigenics plant in south Cobb County and who sponsored legislation to curb ethylene oxide emissions.

Janet Rau, president of Stop Sterigenics – Georgia, said she felt “absolute anger” hearing about EPA obstruction on air testing from a reporter.

“We were begging for air testing before Sterigenics got their new equipment in,” she said. “We’ll never know what was in the air just two years ago.”

The founders of Stop Sterigenics say their fight it not over as long as ethylene oxide is still widely used across the United States.

“We’re not done,” said Donnell. “Obviously our focus is Sterigenics, but it’s not limited to Sterigenics. We’re going try to get this movement to really be pushed on a national level by as many people as we can get.”