By Madeline Laguaite and Jillian Tracy

When Holly Maxwell was about 10, her mother began teaching her how to sew.

It was a skill that proved useful for Maxwell’s relatives. Her mother sewed for the family, and her paternal grandmother made dresses for various women in Buford, where Maxwell grew up. She recalls how as a child, she used her Singer Little Touch & Sew to create a wardrobe for her Barbie dolls.

Sewing ultimately became just a hobby for Maxwell as she pursued a career in the financial world. Today, as a retired banking executive, she’s doing something that she could not have imagined when she took her first sewing lessons nearly 50 years ago: She’s making masks to protect health care workers in a global pandemic.

“It really comes down to ‘It’s either this or nothing,’ ” says Maxwell, who sews masks for hospital staff and others in the Athens area and is an active member of two mask-making Facebook groups.

The masks she sews are not medical grade, and they are not meant to be used by themselves by health care workers.

“They’re going to put something on their face if they can,” Maxwell says of medical professionals.

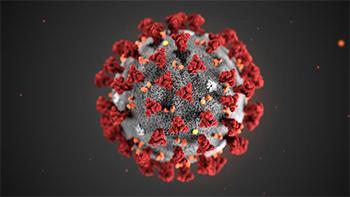

The outbreak of COVID-19, a respiratory illness caused by the novel coronavirus, has led to hundreds of thousands of confirmed cases in the United States. The U.S. has recorded more COVID-19 deaths than any other country — though it’s also one of the most populous countries on Earth.

A surge in hospitalizations has led to shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), like N95 masks, medical gowns and respirators, necessary to protect front-line health care workers from exposure to the virus while they treat patients.

The FDA recommends that health care facilities use conservation strategies — such as using reusable gowns, reusing surgical masks, and prioritizing the use of supplies — to mitigate any shortages in the supply chain. And because of shortages, prices of PPE have surged.

Homemade masks don’t qualify as PPE, because their effectiveness in protecting health care workers has not been confirmed. But given the demand, health care workers have reached out to Facebook groups and businesses asking for help. Sewing groups have formed in metro Atlanta, in hard-hit Albany in southwest Georgia, and elsewhere.

People like Maxwell, 58, have been doing their part.

When the COVID-19 outbreak first reached America, the CDC recommended that people wash their hands frequently and stay at least six feet away from other people in public spaces. Recently, the agency added the recommendation that most people wear cloth face coverings in public. The agency even posted instructions for sewing handmade masks.

The masks that Maxwell sews for health care workers and first responders are not meant to be worn alone. They are made to cover N95 respirators, to help keep those masks clean and prolong their usability. Her masks are made by using two layers of woven cotton. She has made some masks with a pocket, so health care workers can add filter fabric — if they have it — for added protection.

“Of course you can wear them just as they are,” Maxwell says, “but they’re not going to have the same protection” as medical-grade masks.

Everyone wants some kind of protection

Maxwell also handles requests from those who work in the financial industry and those who need to wear masks due to a family member’s health. She doesn’t charge for these hand-sewn masks; she doesn’t “want to profit in any way from the hardship of others.”

The Rev. Margaret Davis is an administrator in the Mask Making for Athens Facebook group, which has drawn more than 1,000 volunteers since its start March 21. Davis says it takes about 30 minutes to make one mask, depending on the skill and experience of the person doing the sewing. One request for masks can typically be filled in one to two days, depending on the amount of masks asked for and the number of volunteers available.

Volunteers are encouraged to work with materials such as cotton fleece or canvas, which are water-repellent but breathable.

Once the masks are finished, they are pressed with a clothing iron to help sterilize them before they are transported to their final destination.

“They’re bagged in Ziplocs after they’re ironed,” Davis says. “The facilities who receive them are instructed to launder them according to their specifications before use as well.”

Volunteers send the masks to local facilities such as Athens Regional Medical Center, the Athens Community Council on Aging, diagnostic centers, nursing homes, dialysis centers, hospices, the kidney clinic of Athens and local home health care workers, as well as law enforcement officers.

Piedmont Athens Regional Medical Center has been accepting donations of cloth masks and other medical supplies that can be used to protect staff and patients while allowing the conservation of surgical masks and N95 respirators.

St. Mary’s Hospital says it has adequate supplies of protective equipment to cover the faces of employees working directly with patients with respiratory issues. But hospital officials are accepting community donations to assist employees who help with non-respiratory patients and those who work for the hospital’s support services.

Athens-based businesses such as Community, a fashion store, and STATE the Label, a garment maker, have also been making masks for health care workers.

Sanni Baumgärtner, the founder and owner of Community, closed her store around mid-March. When she heard about the shortages of PPE, she got in touch with David Bradley, president and CEO of the Athens Area Chamber of Commerce, who connected her with an employee at Piedmont Athens.

Baumgärtner created a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for materials and to cover the labor cost of the seamstresses. It’s raised over $9,000 so far. Although Community is offering to compensate everyone sewing masks through the fundraiser, many people just want to volunteer.

“I think the demand right now is unlimited,” she says. “We’re just trying to make as many as we can, as quickly as we can.”

Not PPE, but useful

It’s not ideal for a health care worker to rely on only a cloth mask, explains Mark Losego, assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Georgia Tech.

One of the biggest problems for medical personnel is aerosolized particles, the tiny particles that stay in the air after a person sneezes or coughs. The virus that causes COVID-19 is able to survive for “several hours to days in aerosols and on surfaces,” according to the National Institutes of Health.

“You can imagine in a hospital setting with a bunch of patients, coughing and stuff, there’s going to be aerosolized particles,” Losego says. “That’s why those health care workers really need to have true respirators that can really filter aerosolized particles versus the mask.” In other words, they need medical-grade masks if possible.

While health care workers should use cloth masks alone as a last resort, the CDC recommends that everyone else use cloth masks when they are outside their homes.

But before making one on your own, Georgia Tech recommends using a simple test to see if the fabric you’re using is up to par:

- Hold the fabric a few inches from a mirror.

- Spray tap water through one layer of dry fabric.

- Check the mirror to see if it’s very wet; if there are only a few small drops, it’s an acceptable fabric to make a mask out of.

Even if you’re wearing a cloth mask while out and about, Losego still recommends staying at least six feet from other people. “We don’t want to have people wear cloth masks and lower their guard,” he says. “It’s not sufficient.”

Homemade masks are not the only local solution popping up to address the lack of protective equipment for health care workers.

There are other community efforts to make protective gear.

The University of Georgia’s College of Engineering, Office of Research, and UGA libraries are working together to produce face shields, a type of PPE that can protect against things like liquid, blood, or other inhalants.

Don Leo, the dean of the College of Engineering, says that in early April, local health care providers reached out to UGA to see if some university facilities could be used to create PPE.

Although health care workers should wear N95 respirators to protect themselves from airborne particles, face shields take it a step further. “With the shield and then with a mask, that gives the health care worker significantly more protection . . . if they’re using both at the same time,” Leo says.

As the pandemic continues, the number of people willing to pitch in and help continues to grow.

Maxwell says the pandemic has proved that there are “some really good folks out there” who just want to do something to help others.

“We all realize that it could easily be one of us or a family member who needs that care,” she says. “We’re all in this together.”

Baumgärtner says she was pleasantly surprised by the local response.

“It’s been really amazing to see that there’s such a community” of people willing to make masks, she says. “I think everybody just feels so helpless right now in the situation, and they want to contribute in a meaningful way.”

Madeline Laguaite is a freelance journalist and a health and medical journalism graduate student at the University of Georgia. She is particularly interested in LGBTQ health and public health. She has a public/professional Twitter at @MLaguaite and a portfolio at www.madelinelaguaite.com.

Jillian Tracy is a journalism student at the University of Georgia. She is interested in the intersection of issues, including politics, media and health. She has a public/professional Twitter at @JillianNTracy and a portfolio at jillianntracy.com