County officials hired a renowned scientist to find answers about Juliette’s water. They scrapped his contract after he refused to keep the data confidential.

By Max Blau

On the same February morning when Juliette residents marched into Gov. Brian Kemp’s office demanding he support legislation to remove coal ash from their town, Monroe County Manager Jim Hedges sent an email to nationally known scientist Avner Vengosh, asking for help.

Hedges wanted to know if Vengosh, of Duke University, would come to Georgia and test drinking water wells near Plant Scherer, the nation’s largest coal-fired plant.

The national spotlight was on Juliette, where the plant is located, following weeks of media coverage related to coal ash. Residents had sought answers after the Altamaha Riverkeeper found troubling levels of toxic heavy metals in dozens of private drinking wells. Some officials had questioned the validity of those findings — noting that Plant Scherer’s operator, Georgia Power, had denied responsibility — but they wanted to know more in case action was needed.

Would Vengosh be able to offer clarity to the complex situation? County officials sure hoped so, they indicated.

They could have found few researchers more qualified than Vengosh. A professor of earth and ocean sciences at Duke, he had not only testified before Congress and the Environmental Protection Agency on coal ash, but had also used an advanced scientific tool to see if coal ash was linked to groundwater contamination.

Within two weeks, Monroe County approved a $50,000 contract for Vengosh. As he prepared for the six-month research project, Juliette residents offered to let him test their wells. By the end of August, he said, the county should have some answers about the contamination.

The timing could not have been more critical: State environmental regulators were on track to decide whether Georgia Power should be granted a permit to leave Plant Scherer’s coal ash in an unlined pit forever.

But the week after the contract was signed, county officials scrapped Vengosh’s contract. They said he was no longer needed, in part because the Georgia General Assembly had provided half a million dollars in funding for the state’s environmental agency to conduct more testing in Juliette and other communities with coal ash. (A top deputy for the governor, however, cautioned that the agency did not have the authority to test private wells – potentially limiting the impact of that funding, according to her remarks to the AJC.)

Emails and records obtained by Georgia Health News reveal how those testing plans went sideways. Residents who had once been thrilled about Vengosh were now angry with their elected officials, and questioned whether state environmental officials would provide unbiased, quality answers.

Vengosh believes his testing would have provided clearer answers about the drinking water crisis in Juliette — at a fraction of the cost of the state testing.

“It was puzzling,” Vengosh told Georgia Health News. “To get that far, to have someone reach out, and then to cancel like that? It’s weird.”

***

After a series of town hall meetings last month, at which Juliette residents pleaded for help, Monroe County officials secured free drinking water for the community and pledged to look into installing water lines. Nearly all of Juliette’s households are currently dependent on well water, because they are outside the reach of water lines serving the cities of Forsyth and Macon.

County Commissioner Larry Evans urged residents at one meeting to “not just jump to conclusions” in the absence of “conclusive evidence.” But the officials also promised to find answers about the severity of Juliette’s water contamination and the source of the pollutants.

“Getting these results back should really begin a whole new conversation,” Commissioner Eddie Rowland assured one constituent in an email.

Plant Scherer’s coal ash ponds, which together hold roughly 4,700 Olympic-sized swimming pools, do not have protective liners to prevent toxic heavy metals from seeping into the groundwater. Drinking wells draw up groundwater from below the surface, along with whatever contaminants might be in it.

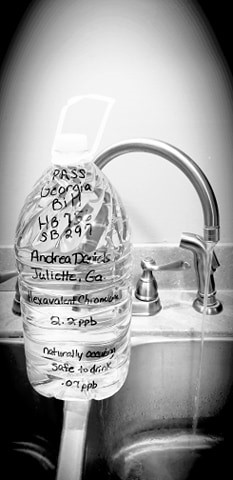

Earlier this year the Altamaha Riverkeeper, an environmental advocacy nonprofit that monitors the entire drainage basin of the Georgia river, revealed that many of the 72 private drinking wells it had tested near Plant Scherer contained hexavalent chromium, the toxic chemical that Erin Brockovich found in California drinking wells, and that has shown up in coal ash disposal sites from Massachusetts to Nevada.

Fletcher Sams, executive director of the Altamaha Riverkeeper, says those tests have also found some presence of additional heavy metals — mercury, boron, calcium, sulfate, barium — that are indicators of coal ash. Exposure to some of those contaminants can lead to long-term health risks including kidney damage (from mercury), reproductive system disruption (from boron), and heart issues (from barium).

“There’s still a lot of misunderstanding there about the water quality,” Vengosh told GHN. “They have two questions: What’s in the ground water? And how is it related to the coal ash pond? We could address both.”

Vengosh, along with a doctoral student, proposed to collect up to 100 samples for a water quality study starting in mid-March. The researchers would also use isotope tracers to determine the source of water contamination by using “geochemical fingerprints” that are unique for different water sources.

According to Vengosh, heavy metals found in groundwater can come either from an industrial source – including coal ash – or naturally occurring sources. Vengosh was looking not only for hexavalent chromium, but a wide range of contaminants that are indicators of coal ash – potentially the ones the Altamaha Riverkeeper had discovered.

But in a February 29 email to Hedges, Vengosh expressed concern that residents were addressing only the occurrence of hexavalent chromium – instead of looking at additional heavy metals – to push legislation to excavate coal ash ponds at Plant Scherer. Based on his research, he said, such a “link could lead to a wrong conclusion” about the contamination source.

In other states, he had found, effluent that had leaked from coal ash ponds could contaminate groundwater with a variety of heavy metals. He had also found, in his well tests in North Carolina, that hexavalent chromium could be naturally occurring instead of from coal ash.

Vengosh was careful to note that even if he found hexavalent chromium to be naturally occurring in Juliette water, that would not necessarily let Georgia Power off the hook as a potential source of contamination. Though drinking water in local wells might not yet be tainted, coal ash could still leak into shallow groundwater and pose a “constant risk” to homeowners’ drinking water.

“Even if the hexavalent chromium found in drinking water wells is not derived from coal ash contamination, there is still high risk of future contamination,” Vengosh wrote.

Juliette needed more data, Vengosh said. County commissioners agreed, approving his contract on March 3. Residents applauded the officials. But little did they know that Vengosh’s proposal would soon be shelved, in part because officials wanted it kept secret.

***

While preparing to send his doctoral student down to Juliette, Vengosh asked if he could test on Georgia Power’s property. Days later, on March 9, Hedges told Vengosh that state Rep. Dale Washburn, whose district includes Juliette, had obtained permission for Vengosh to test Georgia Power’s wells.

That same day, Georgia Public Broadcasting published a story in which Vengosh reiterated the point he had made to Hedges about hexavalent chromium — and stated that Georgia Power had an obligation to remove the coal ash so “it will not allow this leaching out of contaminants” into the groundwater.

But as Juliette residents prepared for a town hall meeting that evening, at which some would volunteer to have their wells tested, policymakers in Atlanta were crafting a proposal that would jeopardize Vengosh’s contract.

On March 9, Georgia Environmental Protection Division officials were finalizing language that would add $500,000 to the state budget for the upcoming year. Records obtained from the EPD show the money, if approved by Gov. Kemp, would pay for two environmental engineers and “third-party testing” for “CCR” — the official acronym for coal ash — and other “emerging issues.”

Rep. Washburn helped persuade Georgia House Speaker David Ralston to approve those funds to help with coal ash testing in Juliette, according to Washburn and Ralston’s spokesperson, Kaleb McMichen. The funding is not solely earmarked for Juliette, however, and can be used for other communities located near coal ash ponds.

Moreover, Kemp’s communication director, Candice Broce, told the AJC that the EPD was unable to test private wells. She suggested the state agency might be able to work with a third-party entity like the University of Georgia.

On March 11, Hedges told Vengosh to postpone the trip. On March 12, Monroe County officials posted on Facebook that they no longer needed Vengosh’s services.

When GHN asked Vengosh about this, he expressed doubts at the state’s ability to outperform his lab’s research. He said that “it’s not really understood how and what resources there are going to be” for the state tests.

EPD spokesman Kevin Chambers declined to answer specific questions about the testing.

“The ironic thing is that we’re [offering testing that’s] much cheaper and has a better analysis,” Vengosh said. “Those state environmental agencies are perhaps good at monitoring, but not at doing independent research.”

***

Pam Wolff, the administrator of a Facebook group on which Juliette residents discuss Plant Scherer’s coal ash ponds, believes Vengosh’s public statements caused the county to step away from the Duke researcher.

“The county couldn’t control what his results would be — or if he would make it public or not,” Wolff said. “As soon as they found that out, they were backing up.”

Indeed, Vengosh had insisted that his findings would have to be made public. In an interview, Monroe County Commission Chairman Greg Tapley conceded that county officials scrapped the contract because they wanted the testing results to be kept confidential, withheld under attorney-client privilege.

“You need to get your facts together, and be close to the vest” when dealing with possible litigation, Tapley said.

At the county commission’s latest meeting on March 17, County Attorney Ben Vaughn advised commissioners not to elaborate further on why Vengosh’s contract was canceled, in part because Monroe County is exploring a potential lawsuit against Georgia Power.

After the board meeting, Commissioner George Emami told GHN that Vengosh’s unwillingness to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) would have hurt the county’s chances of building a case against Georgia Power.

“If we do have to litigate, we can’t have our findings out there for [Georgia] Power to pick apart early,” Emami told GHN. “Once discovery happens, they get it, but not before we determine if we’ve been injured. We’ve said we would be happy to turn over results, and make them public, if we determined that we were not injured.”

Wolff and other residents say county officials have not consulted them about the lawsuit. Instead of potential litigation, they would have rather seen testing results as soon as possible.

Ahead of potential EPD testing, Tapley told GHN the county will still pay $10,000 to a local firm, Harbin Engineering, to conduct a limited set of well tests. Emails obtained by GHN show the firm is now sampling private wells in what amounts to a scaled-back version of the Altamaha Riverkeeper’s earlier testing.

Sams, the riverkeeper’s executive director, says he is worried that the current and future testing plans will not yield any new answers about the state of the groundwater or the source of contamination.

“Unless you’re doing the full research, the answers will remain inconclusive,” Sams said. We need to move forward beyond our basic picture so far and find more information.”

Nearly a month after Juliette residents demanded support from the governor, McMichen, the spokesman for Speaker Ralston, says new expenditures on the unfolding COVID-19 crisis could throw the state’s appropriation for water testing into question.

“I wouldn’t count anything in the [state budget] as certain,” he told GHN. “We will have to wait and see what is and is not possible once the current situation stabilizes.”

Vengosh, for his part, says he still hopes to provide “an objective evaluation” of Juliette’s groundwater. He’s committed to coming to Georgia if an independent party can fund the study. So far, no private group has stepped up to do so.

“All we want is the truth,” Wolff said. “We feel Vengosh could lead us to the truth.”

Max Blau is an Atlanta-based journalist who writes narrative and investigative stories, which have recently appeared in Atlanta magazine, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.