Work teams using heavy equipment began digging up soil contaminated with lead from an empty lot in west Atlanta on Monday morning. It’s the start of an Environmental Protection Agency cleanup action that will take months to complete.

Targeting a neighborhood near Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the EPA has found unsafe levels of lead — a powerful neurotoxin —in the soil of more than half of the 124 yards already examined.

And now the EPA says that it’s considering expanding its investigation beyond the 368 properties currently under scrutiny.

After a community meeting last week, an EPA official told Georgia Health News that it had tested 19 properties around the boundary of the contamination zone and 12 of them showed a problem with lead.

There are no natural barriers that would separate the current testing zone from surrounding neighborhoods, suggesting that the area of contamination could be greater than first believed.

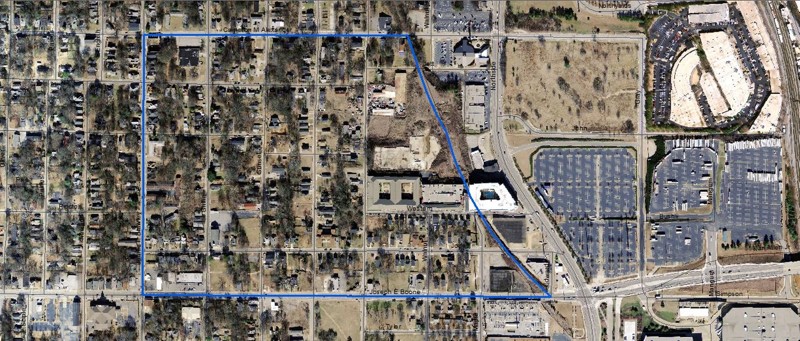

The initial EPA investigation has targeted roughly 35 city blocks between Joseph E. Boone Boulevard on the south, Cameron Alexander Boulevard on the north, James P. Brawley Drive on the west, and an old CSX rail line on the east.

Chuck Berry, an EPA on-scene coordinator, said the agency has now $1.8 million allocated for soil removal and yard restoration, but that more funding will be needed.

“We’re looking at the possibility of expanding the [testing] site,’’ he said.

A spokesman for the city of Atlanta said the city was monitoring developments in the neighborhood.

“This is a matter that is handled at the federal level,” the spokesman said in a statement. “The city has had representation during public meetings to address questions or concerns, but the city does not have a regulatory role, and decisions made during the investigation are within the purview of the EPA.’’

Emory professor Eri Saikawa, whose team discovered the lead problem in 2018, said that “it’s likely there’s contamination outside the boundary’’ of the testing area.

“We’re suggesting they do the testing more broadly,’’ she said. “Having more data helps. We don’t know the scope of the problem.’’

Last Thursday’s community meeting, held at a nearby YMCA, appeared to draw more government officials than local residents. But at least two homeowners who attended signed up for their yards to be tested.

Tarajee Najeeullah, who lives on Elm Street, was one. She said she was concerned about the health of children living in her home. Lead exposure is especially hazardous to children.

The Emory team began analyzing the soil in the westside area in July 2018 and found that it contained high concentrations of lead. Those findings led to the EPA investigation.

Lead contamination in soil can come from the residue of smelters and other industrial processes, as well as from lead paint, and some areas are still contaminated by vehicle exhaust from the era of leaded gasoline.

EPA researchers have speculated that the homes in the westside Atlanta neighborhood were built on top of slag, a byproduct of smelting, spread from nearby foundries and used to fill in low-lying areas.

Prior to 1974, slag was commonly used as a fill material, Berry said at the community meeting. It’s a problem that has surfaced nationwide, he said. “Slag can have varying amounts of heavy metals.’’

Along with digging up to two feet of soil, Berry said, crews will also remove trees. It’s unavoidable, he told residents at the community meeting, adding that the soil around tree roots is contaminated.

But the tree removal, already begun on Elm Avenue, came as a shock to at least one area resident.

“I am horrified by all of the trees that have been taken down,’’ said Rosario Hernandez, a community leader, at the EPA meeting.

“This was never told to us,’’ she told Berry. “Our trees are our ecosystem.’’ She added that tree removal could also exacerbate the neighborhood’s flooding problems. “I never knew it could happen like this.’’

Berry acknowledged to a reporter that agency’s communication with residents in every situation can be improved.

The EPA will replace trees and shrubs, as well as soil, and plant sod, if homeowners whose yards are dug up request it.

The federal agency has officially designated the westside area as a “Superfund removal action,” a separate classification from a Superfund site. If the area is designated a Superfund site, more federal dollars would be available.

The EPA is giving high priority to homes inhabited by pregnant women or children under age 6.

Children can absorb as much as 90% more lead into their bodies than can adults. Researchers have found that even at low levels, lead can damage a child’s brain, lowering intelligence and damaging the ability to control behavior and attention. At higher levels, lead can affect growth, and it can replace iron in the blood, leading to anemia and fatigue.

There is no safe level of lead exposure, the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

In adults, lead poisoning can cause a higher risk of high blood pressure and damage the nerves and kidneys. It also can cause miscarriages.

The EPA’s threshold for unsafe lead contamination in soil is 400 parts per million.

In an empty lot across the street from Hernandez’s properties, the Emory team got a reading of more than 2,000 parts per million — five times the EPA’s threshold for remediation and removal. And the EPA said it has found levels as high as 3,400 parts per million at one location.

This article is published in collaboration with the AJC and the Georgia News Lab.