Rosario Hernandez regularly gardens with her grandchildren at her two Atlanta properties in the English Avenue district, about a mile from Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

So Hernandez, who works with Historic Westside Gardens, was alarmed when an Emory University team analyzed the soil in July 2018 and discovered it contained unsafe concentrations of lead — a potent neurotoxin that is especially dangerous to children.

The next month, a community member at a local tomato festival delivered a piece of a rock-like material from the area to Emory professor Eri Saikawa and an official with the federal Environmental Protection Agency. They tested it on the spot, using a hand-held X-ray Fluorescence device, which resembles a ray gun from a science fiction film.

Like the samples from Hernandez’s yards, the material also exceeded the EPA’s lead threshold.

“That’s when we realized it was a really big issue,” said Saikawa.

The Emory findings led to an investigation by the EPA, which has since expanded the area of potential contamination to 368 properties, covering roughly 35 city blocks. The agency said it has results from soil sampling 124 of them. More than half, 64, have at least one area with elevated levels of lead in the soil.

“We’re still in the sampling phase,’’ said Terrence Byrd, federal on-scene coordinator for the EPA. But he added, “We do have enough information to say removal is warranted.’’

Saikawa and community members are urging residents to test children for lead poisoning, but have encountered some mistrust. There apparently has been no separate, systematic effort by local or state health officials to test children in the mostly poor, largely African-American community for lead exposure, Georgia Health News found.

Growing food is popular in the west Atlanta area, with 160 families in the area having personal gardens, said Historic Westside Gardens Executive Director Gil Frank. He helped the Emory team, led by Saikawa and doctoral student Sam Peters, secure the soil testing grant from the Emory HERCULES Exposome Research Center.

“I was interested in what is the health risk to the gardens and the children there,’’ Frank said. “Nobody was looking at possible contamination.’’

Lead contamination in soil has popped up as a health hazard in communities across the United States, the unseen residue of smelters and other industrial processes but also a product of lead paint and vehicle exhaust from the era of leaded gasoline.

On Atlanta’s westside, Emory and EPA researchers speculate that homes were built on top of slag, a byproduct of smelting, spread from nearby foundries and used to fill in low-lying areas.

A recent visit by a reporter revealed chunks of slag lay in an empty lot across the street from Hernandez’s property on Elm Street. Other pieces were scattered on the lot next to her home.

“I didn’t even know what slag was,’’ said Hernandez.

Although EPA is still sampling, the agency has officially designated the westside area as a “Superfund removal action,” a separate classification from a Superfund site.

Georgia Health News learned details of the EPA’s removal plans from a memo prepared by the state Environmental Protection Division, obtained under an open records request.

Removal actions costs are capped at $2 million over 12 months, according to the state memo. That could include excavating soils and slag until the lead readings fall below the EPA limits. The EPA would then restore the removal sites to their original condition.

The funding may cover the cleanup of the currently identified properties, but more money may be needed to decontaminate the entire neighborhood, according to the state memo. If the area is designated a Superfund site, more federal dollars would be available.

The EPA is prioritizing homes that have children under age 6 or pregnant women, the state memo said.

Because it’s difficult to determine the source of the slag, the records stated, “EPA does not anticipate identifying any responsible parties.’’

The EPA said Wednesday that it plans to begin decontaminating properties in the first quarter of next year.

Toxic to children

Lead is especially dangerous to children, who can absorb as much as 90% more lead into their bodies than adults. Researchers have found that even at low levels, lead can damage a child’s brain, lowering intelligence and damaging the ability to control their behavior and attention. At higher levels, lead can affect growth, and it can replace iron in the blood, leading to anemia and fatigue.

There is no safe level of lead exposure, the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

In adults, lead poisoning can cause an increased risk of high blood pressure and damage the nerves and kidneys. It also can cause miscarriages.

Lead poisoning can come from several sources, including water, paint, even certain toys and imported candy.

The EPA’s threshold for unsafe lead contamination in soil is 400 parts per million, though one expert told Georgia Health News that even a reading of 75 parts per million should raise concern in areas where kids play.

“Kids are always sticking their hands (in dirt) and toys in their mouth,’’ said Jay Lessl, program coordinator for the Soil, Plant, and Water Laboratory at the University of Georgia.

On one of Hernandez’s properties, the lead results were 560 parts per million in the front yard and 690 parts per million in the back — each significantly greater than the EPA’s threshold of 400 parts per million. Next door, where Hernandez’s grandchildren have lived, the results were also elevated, including a reading of 520 parts per million in the playground area.

In an empty lot across the street from Hernandez, the Emory team got a reading of more than 2,000 parts per million — five times the EPA’s threshold for remediation and removal. And the EPA said it has found levels as high as 3,400 parts per million.

Many kids not tested

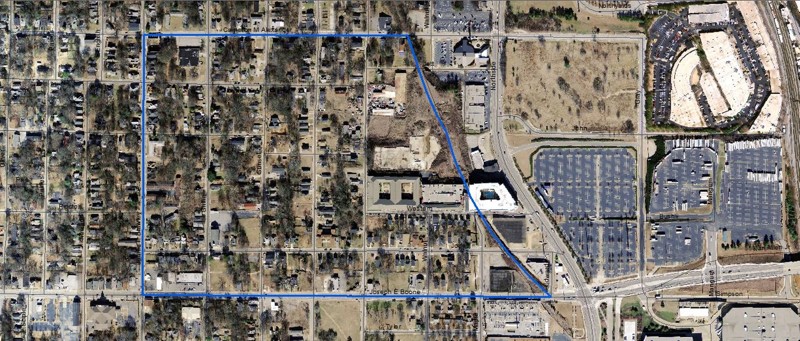

The EPA investigation has targeted properties between Joseph E. Boone Boulevard on the south, Cameron Alexander Boulevard on the north, James P. Brawley Drive on the west, and an old CSX rail line on the east. The surrounding area is home to about 3,700 people, more than 40% of whom live in poverty, according to U.S. Census data.

Several houses there are boarded up alongside streets with uneven, pocked pavement. Other homes have flowers and gardens. The agency’s Superfund and Emergency Management Division, which includes the emergency response program, is overseeing the investigation.

The EPA did not publicize the contamination through a press release.

In March and July, the agency sent informational letters and fact sheets to residents, homeowners, property and business owners, and staff have gone door-to-door to seek access agreements to conduct soil sampling at selected properties. The agency also has notified state environmental regulators.

“EPA recommends you limit your direct exposure to the soil in your yard, make sure you and your family wash your hands and toys after playing in the yard, and remove shoes before entering the residence,’’ said an EPA letter to Hernandez this year, in announcing the results of testing on her properties.

Hernandez, concerned about her grandchildren’s health, is getting them tested for lead levels, and is urging neighbors to get their kids tested, too.

Neither Saikawa nor Hernandez say they know of children whose blood has shown high levels of lead.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found historical evidence of lead poisoning in children in the Elm Street ZIP code, where Hernandez and her grandchildren live, and the ZIP code next to it, in Georgia Department of Health data obtained by the Georgia News Lab. The state collects lead test results from children covered by Medicaid, the health insurance program for the poor, and from kids who have been tested outside that program.

In 2005, the data show, 11.7% of children tested for lead exposure in Hernandez’s ZIP code had high levels of the heavy metal, and 7.8% of children tested in the adjacent ZIP code had high levels. By 2012, the percentage of children with a high concentration of lead had dropped to 3.9% in Hernandez’s ZIP code, and to 2.8% in the one next to it. No children tested in Hernandez’s ZIP code were found with elevated blood lead levels from 2013 through 2018, according to the state’s data, but some children from the adjacent ZIP code showed elevated levels in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

“Most of the people I have talked to said they have not had their kids tested,’’ Saikawa said. “I was told there was fear in doing that.”

Saikawa, noting this reluctance, has asked families if she can take toenail samples from their children to check for contamination. She says she has permission from parents of 10 children, and is working to get the consent for more kids to be tested.

EPA: ‘We really need help’

Byrd, the EPA official, said the agency is having difficulty contacting or getting permission to take soil samples on the remaining 200-plus properties in the neighborhood. More than 83% of residents rent, according to census data. Many homes are owned by out-of-state corporations, Byrd said.

“We really need help from the public with access,’’ Byrd said. If a property has elevated levels of lead, “We will clean it up at no cost to them.’’

Lessl, the UGA soil expert, says the cost of scraping off the soil, removing it, and bringing in new topsoil is very expensive.

He said excavation costs would vary, but for an average-sized home it could range between $8,000 to $12,000 to remove and dispose of contaminated soil, add back fill with uncontaminated topsoil and regrade the property.

State Rep. Mable Thomas, D-Atlanta, who represents the westside area in the state Legislature, said the community’s feelings are mixed about the EPA activity.

“Some people are happy to go along with remediation,’’ Thomas said. “Other people say to me that they believe this is another effort to push residents out of the westside.’’

“If there has to be remediation, the people should be made whole,’’ she added. “Low-wealth, working-class neighborhoods have a right to have a voice in their own community.’’

And the children there should be tested for high lead levels, Thomas said. “It would be a good thing to check out.’’

Residents of nearby neighborhoods told Georgia Health News about the history of slag being used as a “fill’’ material.

“If you look at most dumps, they are in minority neighborhoods,’’ said Colette Haywood, who lives on Foundry Street.

She and another resident, Annie Moore, said they want the EPA to widen their soil sampling territory.

“I would like them to test my area,’’ Moore said.

She has a big chunk of slag in her yard, she added.

Georgia News Lab Deputy Editor Laura Corley and AJC data specialists John Perry and Jennifer Peebles contributed to this reporting. Email Andy Miller at amiller@georgiahealthnews.com

Neighborhood profile

The mostly African-American neighborhood in west Atlanta where officials have found lead contamination has high unemployment and poverty, along with many unoccupied homes, according to U.S. Census data.

Population: 3,698

Children under 5: 275

Black: 79.2%

Hispanic: 2.8%

Households: 1,630

Households with children: 203

Unemployment: 20.4%

Without health insurance: 21.1%

In poverty: 41.8%

Children under 5 in poverty: 45.5%

Housing units: 3,067

Vacant housing units: 46.9%

Renter-occupied: 83.3% (percent of occupied units)

Source: 2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates

About the story

Andy Miller, a former Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter, is the editor and CEO of Georgia Health News, a nonprofit news site covering health care in Georgia. Miller reported this story with the AJC and the Georgia News Lab, an investigative reporting collaboration that includes the AJC and collegiate journalism programs in Georgia. It was produced with the help of a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, a 50-year-old philanthropy that supports investigative journalism in the United States and abroad.