By Amber Perry

In the seven years since she lost her brother, Tori Madison has slowly come to realize a new purpose in life.

Madison has learned to use her own recovery from grief to find ways to help others in trouble. That journey has led her to develop a phone application for college students in substance abuse recovery.

Earlier this year, Madison was accepted into the It Takes a Village Initiative Pre-Accelerator Program through the Atlanta Tech Village, which is a diversity and Inclusion program for women and people of color. It’s a 16-week program in which students receive mentorship and leadership development as they work to develop tech products.

The addiction issue has personal resonance for Madison. She lost her 22-year-old brother, Trent, to a heroin overdose when she herself was only 23.

Substance abuse is an ever-present concern in the college community, affecting more than a third of the collegiate population, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In one of Madison’s Facebook posts, there’s a picture of her and her brother — two siblings, a year apart in age, inseparable, happy and on vacation.

But some memories are not so happy. She recalls an incident during her senior year at the University of Alabama, when she woke up to 12 missed phone calls. Trent had been found on the floor of his apartment in Tuscaloosa, Ala., unconscious and not breathing. He survived this incident, but when he regained consciousness, he immediately asked, “Who knows about this? How many people know?”

Those anxious questions from a man in trouble illustrate the stigma attached to alcohol and drug dependency. Too often, people in the grip of addiction fear being publicly shamed, so they don’t reach out for help. And the addiction simply gets stronger.

“The negative stigma behind drug abuse is one of the main reasons behind kids dying. They are dying in silence,” Madison says.

Jason Callis, the former director of the Collegiate Recovery Community (CRC), says students keep addiction under wraps partly because of their beliefs about campus culture. They think substance abuse is the norm and they should be able to handle it.

“Everybody thinks that everybody else is drinking when in reality, everybody else is not drinking,” Callis says. But the belief gets treated as reality.

Callis says he has even heard professors, when they talk to students about an upcoming Friday class, joke that the students may not show up sober. “They will tell the students, ‘Don’t go too hard on Thursday,’ like it’s expected.”

In this environment, many students feel it’s OK to experiment with drugs or drink until they black out, Callis says.

He helped start the CRC in 2013 on the University of Georgia campus. It provides support to students in recovery by hosting weekly meetings and team-building events.

“When I think about the number of schools that still aren’t willing to start recovery programs – it’s almost backing up that shame,” Callis says. “It’s almost as if they’re not willing to provide the solution.”

Moving beyond sorrow

While some people are recovering from addiction, the past seven years have been a different kind of recovery journey for Madison. “Everyone is recovering from something,” she says, noting that her own journey has been a “recovery from grief and sorrow.”

A big part of that journey has been self-discovery. “Part of my identity was so wrapped up in having a sibling,” Madison says. “He was my only sibling. And so, it was asking, ‘What does my life look like now? What do I really want for myself?’ ”

Madison began working for Uber Eats and helped launch its app. She left to pursue a post-baccalaureate in health and wellness coaching, where she familiarized herself with behavioral change methods and theory.

She aspired to be a coach who teaches “radical self-love,” a concept that she embraced after the loss of her brother. “I had let the sadness and depression consume my life and take over,” says Madison, who lives in Atlanta.

She says radical self-love is an awakening of the heart – training the mind to think differently. This notion is the driving force behind her app’s model – teaching those in recovery to lead a fulfilling life to the best of their ability.

Combining her experience in sales, marketing and technology, her love for start-ups and her own personal recovery journey, originally named For Good, “a community active in substance abuse recovery, empowering self-change”, became Madison’s new venture. Madison is currently rebranding the app under the name My Recovery.

Madison is in the customer discovery phase, speaking with people in recovery and sharing her link, where users are prompted to answer a series of questions that fit her call to action, asking “how their recovery journey is really going.”

Tyler Vance is the current graduate assistant to the CRC and is in long-term recovery. Vance got sober in July 2016, on the day he signed a court document for his second DUI.

Vance says the college culture was a big contributor to his substance abuse. “It was the social atmosphere and the total amount of freedom, the ability to skip class and not really having to pay for it,” Vance said.

Vance describes his time in a fraternity where alcohol and drugs were central to the culture, and soon became the focus of everything for him. “I was going to change the way I felt no matter what,” he recalls.

Later, he began to disconnect from everyone else. He began to isolate himself. “I had a lot of shame in my drinking before I got sober,” Vance says. “I’ve let a lot of that go.”

Ready for the challenge

Madison hopes her app will mitigate the isolation and the sense of shame on college campuses.

Many students use some sort of app, whether for some practical task, for a daily devotional or meditation. But for a person dealing with addiction, it’s tough to replace face-to-face contact, whether that be with another person in recovery or with a psychologist, according to Callis.

Still another challenge is the abundance of health apps already on the market. In a survey conducted by the World Health Organization, among 15,000 mobile health apps, 29 percent were focused on mental health.

“Any good idea you have, someone else has already done it and has built an app for it,” says Emuel Aldridge, professor of the New Media Institute in the Grady College at UGA.

Madison plans to use what’s called gamification – implementing a rewards system inherent to using the app, much like picking up a colored chip at an AA meeting to mark sobriety time.

Health apps like Madison’s are a supplement to conventional care rather than a replacement for it, says John Weatherford, a New Media Institute professor. “I don’t think anyone is envisioning a future without doctors or a future only mediated through technology,” Weatherford says.

But apps offer a solution to the convenience problem. Medical care can be expensive and take time to obtain, according to Weatherford and Aldridge, whereas the app can be virtually free and already in your pocket or in your hand.

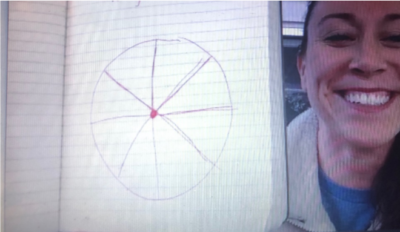

Madison is unwavering in her determination to make a difference. She wants to introduce the “wellness wheel.” It consists of different pieces, one for each area of wellness, such as physical activity and diet. These are defined by user input. The purpose of the app is to analyze the input and offer suggestions on areas that are lacking through evidence-based research.

“The first step towards change and creating more positive, healthy lifestyle choices is self-awareness,” Madison says.

The app is expected to launch in April 2020.

Amber Perry is a freelance journalist and a journalism graduate student at the University of Georgia.