David Carmon’s body began to shut down just three days after a mosquito bite over Labor Day weekend. He arrived at a Gainesville emergency room extremely ill.

No one knew what was wrong.

“They ran every test,” says his wife, Jessie. “By the fifth day, he was paralyzed, on a respirator and fighting for his life.”

Carmon, 53, was eventually diagnosed with West Nile virus, sometimes called just West Nile or WNV. And he’s still fighting the mosquito-borne disease five months later.

He’s able to speak, thanks to a tracheostomy, a surgically created opening to maintain his airway. But even a brief conversation can be taxing. He wants to feel normal again — to talk, to eat and to breathe without machines or assistance.

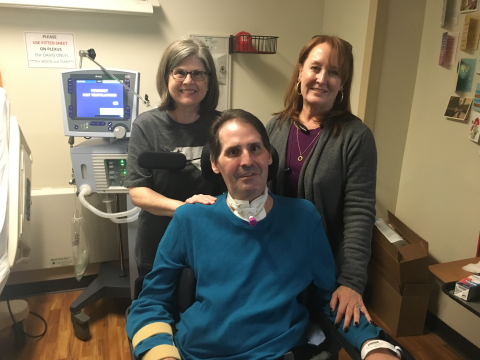

“I want to be able to spend time at home,” Carmon says while at Atlanta’s Shepherd Center, a rehabilitation facility where he recently has been getting care.

Carmon says he is ready to leave, but remained a bit apprehensive.

“It’s uncharted territory,” he says with a surprisingly strong smile.

The transfer to the couple’s Gainesville home from the Shepherd Center occurred Friday.

He is still mostly paralyzed, and has very little movement in his fingers. He requires a support to hold his head upright.

Carmon’s case is unusually severe. The odds are good that most people exposed to WNV will experience no more than a stinging sensation (when the mosquito bites them). Infectious disease experts say only 1 in 5 people who contract the virus will develop a fever or other symptoms.

“And of those, only 1 out of 150 infected people will develop a serious, sometimes fatal illness from WNV,” according to the CDC data.

Those statistics may sound reassuring. But there are no vaccines to prevent WNV or specific medicines to treat it, the CDC says. And Georgia has a lot of people, plus a lot of mosquitoes in peak season. The risk is definitely real.

The state Department of Public Health says that preliminary data show 36 confirmed cases of West Nile virus in Georgia in 2018. Two WNV-associated deaths occurred, says agency spokeswoman Nancy Nydam. That’s down from the 2017 final report of 48 cases with seven deaths reported across 32 counties, says Nydam.

Carmon was in Northeast Georgia Medical Center’s intensive care unit from Sept. 6 until Oct. 2. He admits he doesn’t remember everything about that time, but he appreciates what the staff did for him.

“They kept me alive,” he says.

Difficult adjustments and daunting expenses

Sandy Bozarth, the infection prevention and control manager at Northeast Georgia, says there are specific tests that can be performed when symptoms indicate “an infection involving the nervous system, such as Guillain-Barre, meningitis or encephalitis.” But these tests take time.

They involve obtaining spinal fluid or blood samples, she says. Once the samples are sent to labs for analysis,” says Bozarth, “the results can take 7 to 10 days.”

For the Carmons, it was the wait of a lifetime.

Following four weeks in ICU and lifesaving treatments (such as the insertion of his ‘trach’ and feeding tube, along with multiple IVs), Carmon’s condition began to stabilize, says his wife.

His medical stability allowed for his transfer to Shepherd Center. He arrived by ambulance. After four months at Shepherd, Carmon will require around-the-clock care at home.

Their insurance covers a large portion of the hospital costs. But when David leaves, the policy covers very little other than respiratory equipment, Jessie says.

The Carmons, like many Georgia families, have turned to “crowdfunding” as a source of income to help pay for their sudden, huge financial burden.

Setting up a GoFundMe page has become a go-to way for people in need of help to pay their doctors and other health providers. Medical fundraisers now account for 1 in 3 of the website’s campaigns, and they bring in more money than any other GoFundMe category, said GoFundMe CEO Rob Solomon, according to a Minnesota Public Radio article.

The Carmon GoFundMe page, which a friend helped Jessie create, says that for the foreseeable future, David will remain confined to a hospital bed and wheelchair. “With no use of his arms, he will be dependent [on help] for every aspect of his daily life.”

The cost of caregivers and therapy could reach more than $25,000 a month. David will need a van specially equipped to transport him to therapy, a backup manual wheelchair, a special chair for bathing, and special home modifications — none of which are covered by insurance, Jessie says. “There will also be medical bills and other expenses we have yet to imagine.’’

And still, Jessie says, they are grateful for many blessings they’ve had along their journey.

“David’s sister has been by our side every minute,” she says. “Sherry has been generous, gracious, kind and so much help to David when I couldn’t be here.”

There’s medical progress, too. “I can say I’m getting stronger,” Carmon says from his wheelchair at Shepherd, as he awaited his transfer home.

The most effective way to protect against WNV infection and all mosquito-borne diseases is to prevent mosquito bites, says the Department of Public Health. Observe the “Five D’s of Prevention” during outdoor activities from early summer through late fall, especially in Georgia.

1. Dusk/Dawn – Mosquitoes carrying WNV usually bite at dusk and dawn, so avoid or limit outdoor activity at these times.

2. Dress – Wear loose-fitting, long sleeved shirts and pants to reduce the amount of exposed skin.

3. DEET – Cover exposed skin with an insect repellent containing DEET, which is the most effective mosquito repellant.

4. Drain – Empty any containers holding standing water because they are excellent breeding grounds for virus-carrying mosquitoes.

5. Doors – Make sure doors and windows are in good repair and fit tightly, and fix torn or damaged screens to keep mosquitoes outside the home.

Judi Kanne, a registered nurse and freelance writer, combines her nursing and journalism backgrounds to write about public health. She lives in Atlanta.