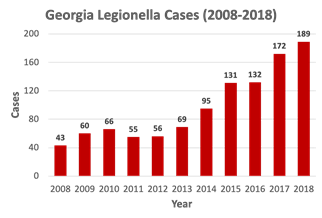

Cases of Legionnaires’ disease have quadrupled in Georgia over the past 10 years, public health statistics show.

That increase mirrors a national trend, with U.S. cases up fivefold since 2000.

About 80 percent of Georgia outbreaks have occurred in health care facilities, according to Cherie Drenzek, state epidemiologist.

Legionella bacteria live in water, and are found naturally in lakes and streams. But they can be dangerous and lethal when they grow in man-made water systems, eventually finding their way into showerheads and sink faucets, where they become aerosolized.

Legionellosis, a respiratory condition, occurs after people breathe in water vapor containing the water-borne bacteria. It can cause a milder infection, Pontiac fever. In more serious cases, it can lead to the pneumonia called Legionnaires’ disease.

Neither illness is spread person to person, but people over age 50 and those with weakened immune systems are more susceptible to developing the disease.

The bacterium and the disease got their names from a severe outbreak of a type of pneumonia among attendees at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976. Scores of people became ill, and at least 29 died. The story made for frightening national headlines, because the illness struck such a specific set of people and initially baffled health officials. The outbreak was eventually traced to the hotel where the Legionnaires had stayed, and the bacterium that caused the illness was identified.

The disease became known as Legionnaires’ disease, and the bacterium was dubbed Legionella. (Pontiac fever, the milder form of the disease, had been reported since the 1960s, but its cause was unknown until the Legionnaires’ outbreak led to the discovery of the pathogen.)

Why the increase in infections in recent years?

“We are not certain why there is a rise in Legionnaires’ disease cases,” says Atlanta’s Chris Edens, epidemiologist on CDC’s Legionella team.

The rise is likely related to a combination of factors, Edens says. He cites the aging population, changes in diagnostic testing practices, and the increased age of buildings and infrastructure as potential causes.

“Possibly increased Legionella in the environment is another concern,” he adds.

Safer water facilities can thwart outbreaks

Legionnaires’ disease patients experience fever, headache and muscle aches, but initially without signs of pneumonia. The fever can affect previously healthy people, as well as those with underlying illnesses. Respiratory symptoms, which indicate pneumonia is developing, occur within 72 hours, according to the CDC.

Pontiac fever patients do not develop pneumonia. Almost all of them fully recover, the CDC says, but about 10 percent of the people with full-fledged Legionnaires’ disease will die. The disease is treatable with antibiotics if caught in time.

Drenzek says there has been increased awareness about Legionella infections, including among health care officials. She says facilities that are considered to be at risk for Legionella are trying to promote better water management systems.

“Legionnaires’ disease is becoming of more interest because it’s really sort of a neglected infectious disease,” says Allison Chamberlain of the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research.

Chamberlain encourages the public to learn more about ongoing Legionella research.

“Legionnaires’ disease is not caused by a vaccine-preventable bug. It’s not a vaccine-preventable disease, and it’s not a communicable infectious disease,” she says. “And it doesn’t have the numbers [of cases] that other infectious diseases have.”

“But [nationwide] the cases have been on the rise since early 2000.”

“While most people won’t get sick, those with underlying respiratory issues or perhaps those who are immuno-compromised are at greater risk,” says Chamberlain.

The probability is low for getting ill, “but it depends on how much Legionella is in the water and who is breathing in the vapor,” she adds.

CDC officials say Legionnaires’ disease in hospitals is widespread and deadly, but also preventable.

Many people being treated at health care facilities, including long-term care facilities and hospitals, have conditions that put them at greater risk of getting sick and dying from Legionnaires’ disease, according to CDC.

Examples of constructed water systems that might grow and spread Legionella include hot tubs, hot water tanks and heaters, and large plumbing systems. Cooling towers also appear to be a problem for health care facilities.

“It’s important to highlight Legionella,” says Drenzek. “It really underscores for us the need to raise awareness.’’

Judi Kanne, a registered nurse and freelance writer, combines her nursing and journalism backgrounds to write about public health. She lives in Atlanta.

The Thanks Mom & Dad Fund helps support our articles on aging issues.