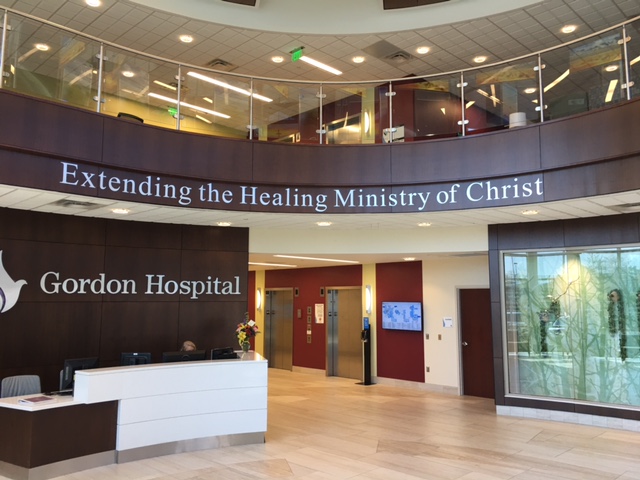

Denny DeSimone, who doesn’t consider herself to be a religious person, had to get used to faith in the workplace when she began working at Gordon Hospital in Calhoun.

The hospital is managed by the Adventist Health System and follows many principles of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. The church has always encouraged healthy lifestyles, including a generally vegetarian diet and abstinence from alcohol and tobacco.

At the hospital, vegan and vegetarian food options are always served, a chaplain is on site during weekdays, and prayer at the end of meetings is normal.

That doesn’t bother DeSimone, a patient care advocate at the northwest Georgia facility.

“If you are not religious, such as myself, you do not have to participate,” she said. “I usually bow my head and remain silent as a sign of respect for others’ religious beliefs.”

In 2016, more than 700 U.S. hospitals were owned by religious organizations. Such facilities often have employees and patients that follow other faiths or are not religious. While employees can opt out of their workplace’s religious practices, some advocacy groups worry that patients may not always have that choice.

It’s particularly problematic as faith-based hospitals expand to fill a void, as in rural areas where access is limited.

For example, almost a third of Catholic hospitals are in rural areas, according to MergerWatch, an organization that works with communities to protect patients’ rights and access to care when religious health systems propose a hospital merger.

The ethical guidelines of Catholic hospitals may prohibit procedures such as abortions, infertility services, contraception and vasectomies, the MergerWatch report notes. (The Catholic Church opposes abortion and any artificial means of preventing pregnancy.)

“In many places where there are no other hospitals, people cannot get the care they need,” said the Rev. Marie Alford-Harkey, a pastor of the Metropolitan Community Churches and president of the Religious Institute, a multi-faith organization that advocates for sexual, gender and reproductive health.

Hospital groups say patients always get evidence-based care, no matter what the company’s faith.

“Some hospitals might be owned by a religious-affiliated entity, but they’re still governed by state and federal regulations,” said Jeff Sunderland, the senior director of communications at the Georgia Hospital Association, which includes more than 170-member hospitals statewide.

Providing the comfort of religion

Chaplain Don Jehle at Gordon Hospital believes in the power of prayer — both for patients and doctors.

“I’m seeing people that have the sense of peace that they can receive from their religious faith that helps them on a totally different level — not just the patients, but also the practitioners,” he said. “Many providers pray with their patients, and they believe that they have better outcomes when they pray.”

Gordon Hospital’s mission statement says its family of professional caregivers are “motivated by Christian values to provide the highest quality physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual healthcare, while extending the healing love of Christ.”

“While we may not heal with a touch or spoken word, we do believe that we can provide caring and compassion for people as Jesus did,” Jehle said.

Gordon Hospital employees take pride in being a five-star hospital, ranked by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The ranking is based on a summary of 57 quality measures across seven areas: mortality, safety of care, readmission, patient experience, effectiveness of care, timeliness of care and efficient use of medical imaging.

Faith is what sets the hospital aside from other organizations, staffers say.

“We provide care for the whole person — the patient’s medical needs as well as spiritual,” said Melissa Gifford, the practice manager of the Northwest Georgia Women’s Care at Gordon Hospital. “Our employees are very engaged and are more than happy to lend a helping hand when it is needed. We treat our patients like they are family, and no one leaves being a stranger.”

St. Mary’s Health Care System in Athens is a part of Trinity Health, a national Catholic health system with facilities in 22 states. Health care and faith are inseparable to Catholic institutions, said Mark Ralston, public relations manager at St. Mary’s.

“Our mission is to serve with Trinity Health in the spirit of the gospel as a compassionate and transforming healing presence within our communities,” he said. “That mission is founded on our core values of reverence for each person, commitment to those who are poor, justice, stewardship and integrity. We see the divine in every human being and strive to serve all people with reverence and respect for the dignity inherent in every person.”

St. Mary’s provides services for rural, Catholic-affiliated hospitals in Lavonia and Greensboro to help combat the servicing problems the rural hospitals may face.

Limiting patients’ options?

There are 5,534 hospitals in the U.S., according to 2016 data from the American Hospital Association, and there are 726 faith-based hospitals, according to Statista. The data shows the number of faith-based hospitals has increased by 141 hospitals since 1995.

While some believe the institutions’ spreading influence addresses health care concerns, others believe there is a negative effect on health outcomes, particularly regarding the limiting reproductive health care and end-of-life choices that religious-affiliated hospitals provide.

For example, “The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services,” a document released in June 2018 by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, discusses which practices a Catholic hospital can provide based on standards of morality.

The Catholic health organizations are not permitted to engage in “immediate material cooperation in actions that are intrinsically immoral,” such as abortion, euthanasia, assisted suicide, and direct sterilization, these guidelines state. These directives prohibit involvement in such things as vasectomies, abortions and tubal ligations.

Two Catholic hospitals in Georgia — St. Mary’s Good Samaritan Hospital in Greensboro and CHI Memorial Hospital in Fort Oglethorpe — are the only hospitals in their respective counties. Patients who want one of the procedures they do not provide must travel elsewhere in the state.

Availability is not the only bone of contention about abortion in the state. While abortion is legal in Georgia, the state requires that a woman receive a medical briefing at least 24 hours before undergoing the procedure. Critics argue that it is a way of discouraging women from having abortions.

A conscience clause is a legislative provision that relieves a person from compliance on religious grounds. In health care, this allows providers to refuse to provide medical services for reasons of religion or conscience. Conscience rights gained further importance with this year’s creation of the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which ensures that health care workers and companies don’t have to participate in medical services they object to for religious reasons. A press release for the division, which is part of the department’s Office for Civil Rights, said it was “established to restore federal enforcement of our nation’s laws that protect the fundamental and unalienable rights of conscience and religious freedom.”

The press release specifically mentions the Church, Coats-Snowe and Weldon Amendments, federal laws that protect health care workers from providing, paying for or training doctors in abortion or sterilization. The release also mentions section 1553 of the Affordable Care Act, which protects those who disagree with assisted suicide. These laws are already in place, but the division’s purpose is to enforce them.

“Laws protecting religious freedom and conscience rights are just empty words on paper if they aren’t enforced,” said Office for Civil Rights Director Roger Severino in the press release. “No one should be forced to choose between helping sick people and living by one’s deepest moral or religious convictions, and the new division will help guarantee that victims of unlawful discrimination find justice.”

Although health care providers’ rights are being protected, what can be done to better inform Georgia patients?

Some have suggested that religiously affiliated hospitals should have to list on their websites the services they choose not to provide, a recommendation that has been enacted in Washington state. Others believe that, as in Illinois, these hospitals should have to advise patients on where the procedures they do not provide can be obtained. Georgia currently does not have such laws.

Emily Webb holds a bachelor’s degree in English from LaGrange College in Georgia and is currently pursuing her master of arts in journalism at the University of Georgia. She has a special interest in lifestyle, religion, health care and food and nutrition. She enjoys writing, reading and traveling. Her current project focuses on exploring the relationship between faith-based health care institutions and access to care