Three Georgia children have been reported this year as having a rare, polio-like health condition, state officials said Wednesday.

They are among the 62 children nationally who have been confirmed with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) in 2018, with at least 65 more cases under investigation, according to the CDC.

There is no known single cause of AFM, whose symptoms include weakness in the arms or legs, and sometimes paralysis.

Since 2014, Georgia public health officials say, that there have been 11 confirmed or probable cases of AFM in the state, with five coming in 2016 alone.

The CDC noticed an apparent increase in this type of acute flaccid paralysis in children in the fall of 2014, at the same time as a nationwide enterovirus outbreak, Nancy Nydam, spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Public Health, said Wednesday. Since that time, the CDC has requested that states report suspected cases.

Dr. Sumit Verma, medical director of the Neuromuscular Program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said Wednesday that the pediatric system has seen 10 to 12 AFM cases since 2016.

AFM was made a reportable condition in Georgia this past summer, but in accordance with CDC recommendations, Public Health had been requesting since autumn 2014 that physicians report suspected cases, Nydam told GHN.

The condition affects the nervous system, specifically the area of the spinal cord called gray matter. It causes the muscles and reflexes in the body to become weak or even paralyzed. Cases of AFM are characterized by a sudden onset of arm or leg weakness and loss of muscle tone and reflexes, CBS News reported.

Its symptoms are likened to those caused by polio, which was eradicated in the U.S. thanks to the polio vaccine. The CDC emphasized that none of the children who developed these symptoms had the polio virus.

Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said Tuesday that so far, no common cause linking these illnesses has been found, NPR reported.

“There is a lot we don’t know about AFM,” Messonnier said during a teleconference for reporters. “I am frustrated that despite all of our efforts, we haven’t been able to identify the cause of this mystery illness.”

The average age of the children affected is about 4, she said, and 90 percent of cases the CDC has been studying since 2014 have involved patients 18 or younger.

Messonnier said scientists don’t fully understand the long-term consequences of the illness. “We know that some patients diagnosed with AFM have recovered quickly, and some continue to have paralysis and require ongoing care,’’ she said, according to NPR.

Dr. Verma of Children’s Healthcare noted that unfortunately there is no cure for acute flaccid myelitis, but he said there are ways to manage the symptoms, and he added that rehabilitation can improve function and quality of life.

He said he became aware of the illness in 2016, when Children’s Healthcare treated a number of kids with the condition. “It’s a very slow rehab and recovery,’’ Verma told GHN. “The majority of kids have persistent weakness.’’

“It’s very rare,’’ he added. “We don’t need to panic on this.”

The CDC’s Messonnier said, “We know this can be frightening for parents. I encourage parents to seek medical care right away if you or your child develops sudden weakness or loss of muscle tone in arms and legs.”

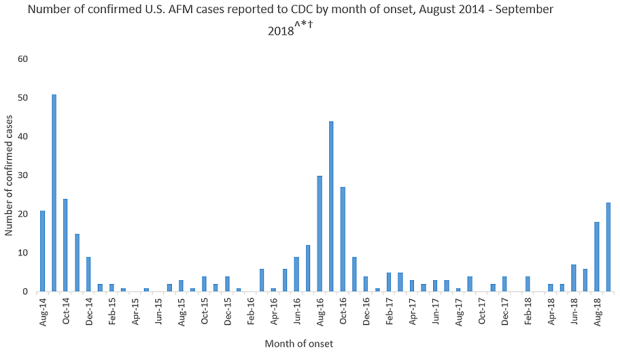

Since the condition was first recognized by CDC in 2014, the agency has confirmed 386 cases nationally through Oct. 16, mostly in children. AFM appears to be seasonal, occurring mostly in the late summer and fall, but appears in greater numbers every other year.

The number of cases in 2018 is on track to match a similar number of cases in 2014 and 2016. But Messonnier cautioned that it would be “premature” to conclude that this year will be the same as the earlier years.

It’s possible that some milder cases haven’t been reported by doctors to their state health department or to the CDC, but Messonnier said she believes the number of such cases would be small, NPR reported.

“This is actually a pretty dramatic disease,” she said. “These kids have a sudden onset of weakness and they are generally seeking medical care and being evaluated by neurologists, infectious disease doctors and their pediatricians and coming to public health awareness.”

Possible causes being considered include viruses that affect the digestive system called enteroviruses, and possibly strains of rhinoviruses, which cause the common cold, she said. The CDC is also considering the possibility that environmental toxins could be triggering the sudden muscle weakness. And it is not ruling out possible genetic disorders.

Messonnier said that the CDC has tested every stool specimen from AFM patients. None has tested positive for poliovirus. She said West Nile virus has not been linked to any of these cases, either.

Messonnier noted the rarity of the condition, emphasizing that it happens in fewer than one in a million children in the nation. So far this year, cases have been confirmed in 22 states, based on findings from MRI studies and the cluster of symptoms a child has.

The state Department of Public Health said the best prevention message is that parents should make sure they and their children do basic things to help keep them healthy, such as washing hands, covering a cough or sneeze, staying home when sick, and making sure they’re up to date on vaccines.

Parents should contact their health care provider as soon as possible if they see any symptom of AFM in your child — for example, if their child is not using his arm.

Symptoms include sudden muscle weakness in the arms or legs, often following a respiratory illness. Some other symptoms may include neck weakness or stiffness; drooping eyelids or a facial droop; and difficulty swallowing or slurred speech, Public Health said.