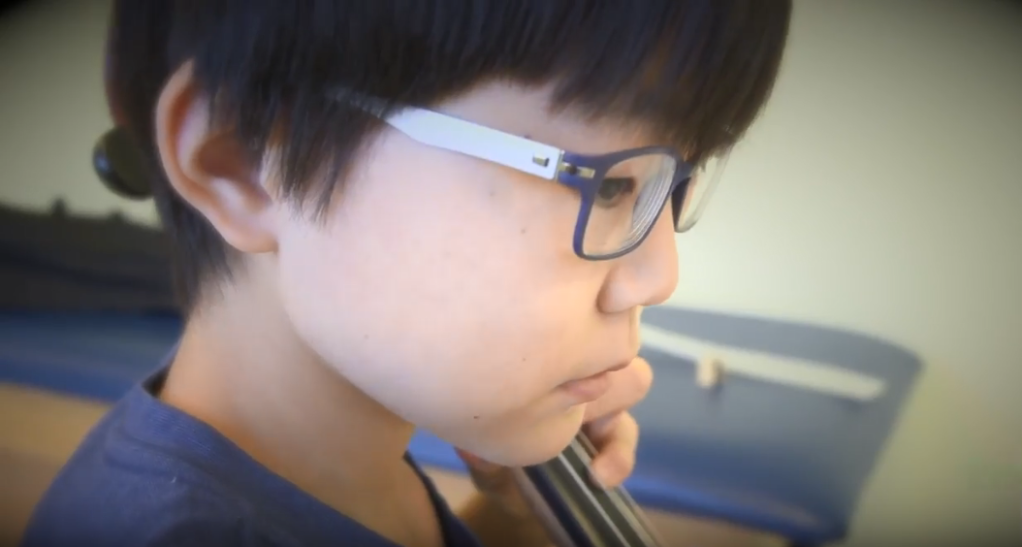

Playing the cello usually takes two hands. But for 12-year-old Christopher Fairchild, it’s a matter of one hand, one prosthetic and a lot of determination.

The challenge for Christopher is that he has been missing his right hand since birth, even though it would otherwise be his dominant hand.

Christopher came to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta for a new prosthesis in late 2015 to help him ride his bike. When he returned for a different prosthesis last year, he had a new goal — he wanted to improve his ability to play the cello. (He still uses the first prosthesis for bike riding.)

At Children’s, he works with Brian Emling, a licensed prosthetist and orthotist. Emling is trained to fit upper and lower limb prosthetic devices, and he enjoys helping children reach their best physical capabilities.

Christopher and Emling are part of the new world of 3D-printable prosthetics that has changed the face of medicine for many people.

Emling recalls that even when the two first met, Christopher was not shy about offering his input, even though he was essentially just a kid talking to a professional. “I don’t think this angle will work,” he said frankly about something they considered trying.

These qualities have made Christopher excellent to work with, says Emling. Thoughtful and creative, the young student is “quick to state his needs and tell me why” he thinks an idea is good or bad.

“At one point, we were discussing the angle of the bow when he seemed to know the device would require a different placement across the cello’s strings,” Emling says. Christopher indicated “the initial angle was going to be too small.”

When the bow’s angle was increased, they learned they could make good contact across all the cello’s strings, explains Emling. And then “with only a few adjustments,” Emling says, “We found the angle’s ‘sweet spot’ and moved on to other areas to improve his ability to play with his new 3D printed prosthesis.”

Attitude is a major factor

Christopher’s mom, Dale Fairchild of Duluth, says she and her husband “chose to adopt Christopher [and his sister Danielle] from birth knowing they were different.” Because of the shape of Danielle’s hand, and her choice of the viola as an instrument, she has not needed a new prosthesis.

“When we’ve had the opportunity to meet people who have had children from birth with similar challenges, there’s always that concern [from the other parents] as to what they can’t do,” she says.

“From my perspective, we’ve never had that,” Fairchild says. “Frankly, I never held the belief that there was a limitation.” She feels, and wants other parents to feel, that children are “different-abled,” not “disabled.”

She says the family is grateful to Children’s Healthcare because the staff has that same mindset. It’s always been, “What we can do to help the children, or accommodate them better so they can do something?” she says.

Fairchild and her husband support a “can do” environment, encouraging kids like Christopher to work with what they have, she says. “It’s a normal thing for them,” Fairchild adds, “although, they do not like it all the time.”

When she sees her children work out their problems and come up with ways to accomplish the things that are important to them, it gives her a good feeling.

Christopher is one of the members of his 7th-grade orchestra, Fairchild says. “We just attended a recent concert and we watched him sit there and have an orchestra connection with the other students.” He can play an instrument just as well as or better than his peers, she says, with perhaps a touch of parental pride.

“To not feel he has a limitation is what is really big for him,” she says.

A revolution in prosthetics

Emling has developed his skills through years of training and practice. His master’s of science program combined two years of education in orthotics and prosthetics followed by two years of residency training.

Experts in the field have developed 3D-printed skin for burn victims, airway splints for infants, facial reconstruction parts for cancer patients and orthopedic implants for retirees, according to the World Health Organization.

The fast-developing field of 3D printing technology has churned out more than 60 million customized hearing-aid shells and ear molds, according to a recent Mosaic Science article. It is also producing thousands of dental crowns and bridges from digital scans of teeth, replacing the traditional wax modeling methods used for centuries.

And limbs. Those amazing artificial arms, hands, legs, and feet are changing the world for many. According to a recent article in The Guardian, “The big [worldwide] hurdle is the lack of trained technicians to fit the artificial limbs.”

As Christopher grows, says Emling, “we may be able to capture the wrist motion, which would get rid of the bow attachment angle issue we ran into initially.” When Emling speaks of this and other advances in prosthetic devices for Christopher and others, he uses jargon that is new and unfamiliar to many, but his enthusiasm shines through.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 3D-printable prosthetics have changed medicine, as engineers and physicians work together helping those who require new body parts.

Today, prosthetic devices made through 3D printing and other advances are fully customized to the wearer, say the experts. Consumer 3D printing is leading to an even bigger revolution.

The prosthetic revolution includes a new public health database just announced this month, supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Defense. The database will try to pinpoint the number of people in the United States who are living without certain limbs. The NIH says the data will include U.S. adults and children and allow researchers to sort the data by age, gender and type of limb loss. (Defense officials are involved in the research because a significant number of people who are missing limbs are wounded war veterans.)

An instrument that lets you feel the music

Christopher’s decision to play the cello may be a reflection of the kind of young man he is. He could have opted instead to play the triangle, a percussion instrument that would require only the use of his left hand.

But the cello is physically more challenging, and more personal. It’s “an instrument that you wrap your body around, and you can feel it resonate as you play,” explains former cellist and music educator Kandy Lamson. She has found over the years that the cello is a favorite of many aspiring musicians.

“The cello has a large range with deep tones in the low range and the ability to go very high if you learn to use your thumb as a capo [a string-tightening device on guitars and some other stringed instruments] and placed on top of the fingerboard with your left hand,’’ she says.

Lamson believes anyone could get a lot of pleasure from playing the cello, even at an introductory level of skill. “It’s a beautiful-sounding instrument,” she says.

Though she does not know Christopher, Lamson says she’s fairly sure a prosthetic right hand could be adjusted to hold the bow.

“As you draw the bow across the strings toward the tip, your hand would have to pivot unless you move your full arm to keep it on the strings,” she explains. “I think it would be a challenge, but it could be done.”

She’ll be happy to know that it can be done, and that it is being done. Thanks to Brian Emling, the wonders of science and a “can-do” spirit, young Christopher Fairchild is using the cello to add a new dimension to his life.

Here’s a video courtesy of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta:

[youtube]https://youtu.be/3N_VdTK7wFs[/youtube]

Judi Kanne, a registered nurse and freelance writer, combines her nursing and journalism backgrounds to write about public health. She lives in Atlanta.