Article updated August 1 at 5:40 p.m.

In a quiet neighborhood in the Atlanta suburbs, a woman sits at her kitchen table, describing what it’s like to suffer from partial facial paralysis, neck pain, hair loss and cardiac symptoms.

“I would take a shower and almost feel like I would pass out,” says Geraldina.

After chasing diagnoses for several months, Geraldina, 38, finally received a test from a doctor and was diagnosed last year with Lyme disease, a tick-borne disease.

Before she tested positive for Lyme, Geraldina was told that she might have fibromyalgia — and was also told on occasion that it was “all in her head.” (Geraldina requested that her last name not be used for privacy concerns.)

With some patients, including Geraldina, the standard antibiotic treatment doesn’t work. Disagreements about treatment are part of a wide-ranging controversy over Lyme disease, which extends to the issues of testing, diagnosis, nomenclature and even the type of tick that’s transmitting the infection.

One thing is certain: Researchers are increasing their estimates of the prevalence of Lyme disease in the United States.

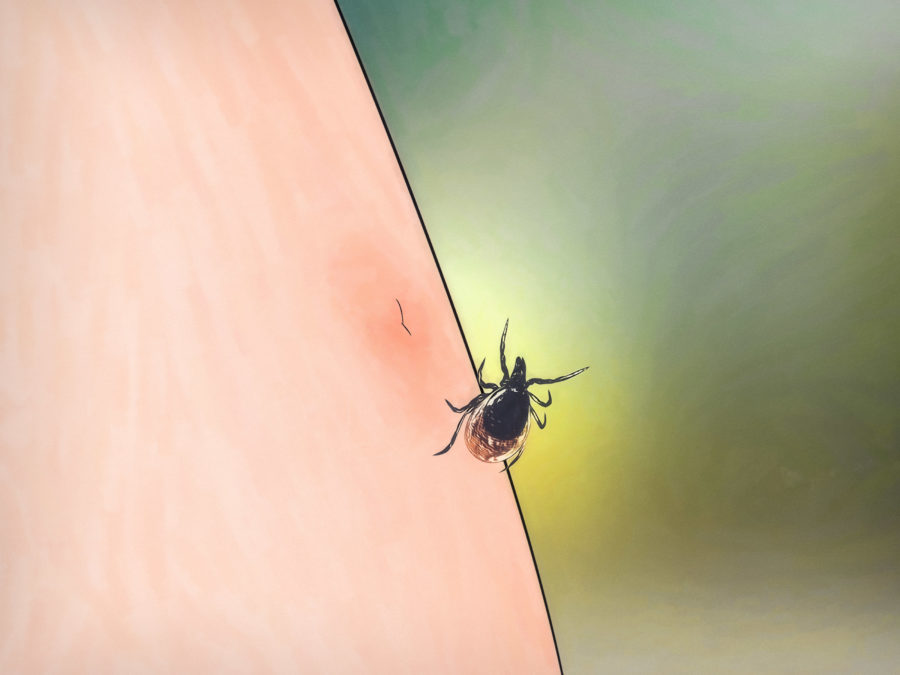

The disease is transmitted by the blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick because it’s a frequent parasite on deer, and the infection is found especially in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic and north-central states. It’s also found on the West Coast.

Typical symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue and a characteristic skin rash. If left untreated, infection can spread to joints, the heart and the nervous system.

Each year, more than 30,000 cases of Lyme disease are reported nationwide, while studies suggest the actual number of people diagnosed with it is more likely about 300,000, the CDC said recently.

The prevalence of Lyme disease in Georgia and the Southeast is reported to be low. The Georgia Department of Public Health says that fewer than 10 cases are reported in the state each year. (Quest Diagnostics issued a press release this week that said Georgia has seen a notable increase in Lyme cases.)

Lyme disease can cause symptoms for quite some time after the standard antibiotic treatment. This is known as “Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome,” by the CDC, with non-specific symptoms like fatigue, pain and muscle and joint aches.

But there’s sharp disagreement on some treatment issues.

What do you call it?

The CDC, an Atlanta-based federal public agency, doesn’t currently use the term ‘‘chronic Lyme disease,” saying it often has been used to describe symptoms in people who have no evidence of a current or past infection.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America doesn’t believe in chronic Lyme disease, says Dr. Jose Vazquez, chief of the Medical College of Georgia’s Division of Infectious Diseases. “We recognize Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, and so does the CDC.”

The Infectious Diseases Society and the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) agree that antibiotics such as doxycycline are appropriate after the rash appears. But the two associations disagree on how long treatment should last, and what can happen afterward, the Associated Press reported in an article last year.

The Infectious Diseases Society says more research is needed on chronic Lyme, but doesn’t recommend long-term antibiotics to treat the condition. ILADS, however, argues on its website that the harm of a continuing Lyme infection outweighs the risks of long-term antibiotic use.

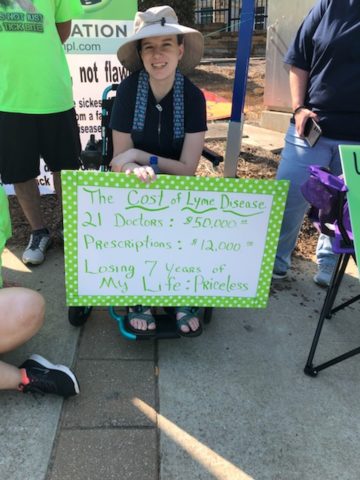

A recent rally at the CDC sought to raise awareness of Lyme sufferers. Geraldina attended the rally, as did Mirenda Campirano, a Texas nurse who says she has been suffering from chronic Lyme for 15 years. She runs an online group called the Lyme Army, a platform for sufferers to speak up, reach out and help others.

The rally sought to protest the CDC’s dismissal of “chronic’’ Lyme disease, saying the term isn’t recognized by the agency nor the mainstream medical community because most Lyme patients do not meet the current case definition “despite clinical symptoms and serologic evidence.”

Dr. Marshall Lyon, an infectious disease specialist at Emory School of Medicine, says he’s one of only a few physicians in metro Atlanta who will see patients looking to be evaluated for Lyme disease.

Very few of them have indications of the disease, Lyon says.

“Unfortunately, a lot of patients whom I see have very real symptoms, and often have been to multiple physicians without a diagnosis,’’ he says. “They want something we can treat.”

Those diagnosed with Lyme who have lingering symptoms, Lyon says, may have had their nerves or immune response damaged by the disease.

Lyon says physicians who treat Lyme patients with long-term antibiotics don’t have enough science to support such a course. “Most of these patients have some sort of disease we haven’t diagnosed,” he says.

Meanwhile, some patients incur huge medical bills while fighting their symptoms, and many of those costs are not covered by insurance. “Patients can rack up $10,000 to $20,000 in debt without improving,” Lyon says.

The CDC issued a statement to GHN that said Lyme disease “is a serious illness that affects hundreds of thousands of people each year in the United States and tragically, some experience long-lasting debilitating consequences from their infection.

“As the nation’s health protection agency, CDC saves lives and protects people from health threats including Lyme disease by basing all public health decisions on the highest quality scientific data developed openly and objectively. CDC continues to raise awareness about the growing threat of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.’’

The CDC says the number of reported tick-borne diseases has more than doubled in 13 years. Diseases spread by ticks vary from region to region across the nation, and those regions are expanding.

Greater tick densities and their expanding geographical range have played a key role in the increase of these diseases, say leading scientists at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases part of the National Institutes of Health, in a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although most cases of Lyme disease are successfully treated with antibiotics, 10 percent to 20 percent of patients report lingering symptoms after antimicrobial therapy. Scientists need to better understand this lingering morbidity, said the commentary authors, Dr. Catharine Paules, Dr. Hilary Marston, Dr. Marshall Bloom and Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Testing and its limitations

Getting an accurate, timely diagnosis can prove difficult.

The CDC currently recommends a two-step process when testing blood for evidence of antibodies against the Lyme disease bacteria. Both steps can be done using the same blood sample.

The accuracy of the test depends upon the stage of the disease, the public health agency says. During the first few weeks of infection, such as when a patient has a rash, the test is expected to be negative. But experts say that an initial negative test doesn’t rule out Lyme.

Several weeks after infection, currently available tests and two-tier testing ‘’have very good sensitivity,’’ the CDC says.

Wendy Adams of the California-based Bay Area Lyme Foundation, though, says testing is “an enormous challenge. Doctors can’t diagnose it based on blood tests. And it’s harder to treat if undiagnosed for years.”

Those in the latter category “have a more serious disease,” she says.

For those patients described as “chronic’’ Lyme patients, “there are different views on what’s causing them to be sick,’’ says Adams, research grant director for the foundation, which funds Lyme research.

“The science and data are important to the discussion. Lyme disease has been underfunded by the government for years,’’ Adams says. “We’ve studied the tick side more than the human side.”

A Lyme disease vaccine used to be available but is not anymore. The manufacturer, SmithKline Beecham, discontinued production of it in 2002, citing insufficient consumer demand.

The CDC said it supports the development of a safe, effective and adequately validated vaccine against this illness.

Public health officials and scientists must build a robust understanding of pathogenesis, design improved diagnostics, and develop preventive vaccines, according to the authors of the tick commentary.

Tick research

When Dr. Kerry Clark, an epidemiologic researcher at the University of North Florida, tested 215 patients in the South who were complaining of similar symptoms, 42 percent of them tested positive for the Lyme Borrelia bacteria, which causes Lyme disease, he reported. A lot of those patients had been told they did not have Lyme.

The black-legged or deer tick, which spreads most of the many Lyme cases in the North, also can be found here in the South. But the CDC says its feeding habits are different in this part of its range, making it less likely to “maintain, sustain, and transmit” Lyme.

Some researchers, including Clark, believe Lyme disease is transmitted in the South by the lone star tick (known for its distinctive “star” marking). The CDC disputes that.

Clark reports that he identified lone star ticks removed from humans who had tested positive for Lyme bacteria. Still, it has not been proved that the lone star tick — which is common in the Southeast and also ranges into much of the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic states — is able to transmit Lyme to humans.

Sufferers like Campirano and Geraldina say they have known for quite some time that Lyme can persist in the body for sustained periods, considering that they both have been symptomatic for years. Both women just want answers about what can be done.

“I want to raise awareness for this. I want people to be maybe sympathetic to people who don’t look sick, but they are suffering,” said Geraldina. “It’s been a hell of a journey, and I do not wish this on my worst enemy.”

And Geraldina put her words into action, attending the rally at the CDC in May.

“The rally was overwhelming and emotional,” said Geraldina, “There were people in wheelchairs, little kids — a woman whose son committed suicide because he couldn’t get help. All of them suffering from Lyme.”

And, as Campirano explained, “We are never going to stop fighting until the world recognizes this terrible disease.”

Here’s a link to audio recordings of Geraldina and Clark

Catherine Morrow is an Atlanta-based freelance journalist who has recovered from a past Lyme disease episode.