“Our citizens are dying. We must act boldly to stop it.”

This statement by President Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis is in response to drug overdoses now killing more people than gun homicides and car crashes combined.

Since 1999, more than 620,000 people in this country have died due to drug overdoses – a death toll significantly larger than the entire population of the city of Atlanta.

Similarly, suicide deaths in the United States have surged to the highest levels in nearly 30 years, with increases in every age group except adults 75 and older. Those increases are troubling enough, but even more so is the trend of the data: The largest increases in suicide rates are occurring in the youngest age groups. From 2007 to 2016, suicide rates for the 10-13 and 14-17 age groups increased by 133 percent and 83 percent, respectively.

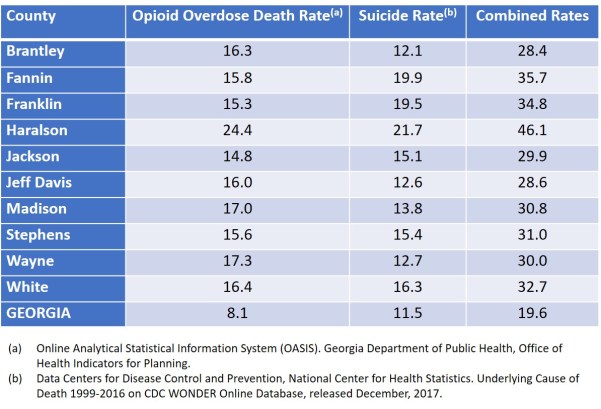

The rising rates of drug overdose and suicide deaths are felt acutely in rural Georgia. Drug overdose deaths increased 35 percent statewide from 2012 to 2016, and the majority are opioid-related. The chart below shows the 10 Georgia counties (all rural) with the highest opioid overdose death rates from 2012 to 2016 and the suicide rates for those counties from 2007 to 2016. The rates are expressed as numbers per 100,000 and the statewide rates are shown at the bottom of the chart.

These are not just numbers. They are people – sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, spouses and partners, colleagues and classmates. Each day, approximately 300 Americans die by drug overdose or suicide, and their deaths are the primary reason why in 2016 overall life expectancy among Americans fell for a second year in a row.

In 2008, President George W. Bush signed into law the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (Parity Act), requiring health insurers to offer mental health and substance use disorder (behavioral health) benefits on par with medical and surgical benefits.

Nearly a decade later, most Georgians continue to encounter insurance coverage of behavioral health care that is far more restrictive than insurance coverage of other medical care. This results in care delays, restrictions, denials and often the loss of life and the destruction of families and communities.

In 2015, Georgians covered by insurance were four times more likely to have to go out-of-network for behavioral health office visits than for primary care, a situation due in large part to behavioral health care providers being paid 19.9 percent less than the Medicare-allowed amounts by insurers. That same year, providers of primary care services were paid 36.6 percent higher than those of behavioral services.

In-network care has lower member co-pays or co-insurance requirements than out-of-network benefits. Insured Georgians have two choices when there is a lack of competent in-network providers due to low payment rates: Pay more and visit out-of-network providers, or forgo the treatment they need and put jobs, families and lives at risk.

Mental health and substance use disorders affect society in ways that go beyond the direct cost of care. Without effective treatment, people with these health conditions may find it difficult to find or maintain a job, may be less able to pursue education and training opportunities, may require more social support services, and are more likely to have their housing stability threatened.

Insurance coverage that is consistent with parity requirements can provide access to treatment and services, which in turn can reduce the difficulties faced by people with mental health and substance use disorders, help their loved ones, increase their independence, and create stronger communities.

Many organizations are advocating for a proposal known as the Georgia PEACH Act (Parity Ensures Access to Crucial Healthcare). It would target critical areas that must be addressed to ensure that coverage for mental health and substance use disorders in Georgia is equal to coverage for other medical conditions. The organizations include the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, Georgia Council on Substance Abuse, Georgians for a Healthy Future, Georgia Psychiatric Physicians Association, MHA of Georgia, NAMI Georgia, Presbyterians for a Better Georgia, and Voices for Georgia’s Children.

In its interim and final reports to President Trump, the Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis made several recommendations, including:

** There needs to be robust enforcement of the Parity Act by the state and federal agencies responsible for implementing the law.

** Such robust enforcement should ensure health plans cannot impose less favorable benefits for mental health and substance use diagnoses versus physical health diagnoses.

** Regulators should be required to levy penalties against health plans that violate the Parity Act.

** Information about parity violations should be made available to the public.

As of October 2017, all Medicaid managed care and CHIP recipients in Georgia were being provided access to mental health and substance use disorder benefits that complied with parity standards, including quantitative and non-quantitative treatment limitations.

Enactment of a Georgia PEACH Act.will ensure that all insured Georgia citizens – not just those covered by Medicaid and CHIP — receive the health care coverage to which they are entitled by law and for which they and/or their employers have paid.

The Georgia PEACH Act would protect families, bolster communities, strengthen the economy and, most importantly, save lives. Georgians are dying. We can and must act boldly to stop it.

For additional information on the Georgia PEACH Act, please see the @PassThePeach accounts on Facebook and Twitter.

Roland J. Behm is chair of the Board of Directors of the Georgia Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention