This is the fourth in a series of articles about health care in Southwest Georgia, an area of the state that has great health needs and challenges, but also some innovative approaches to such problems. The series is the product of a collaboration between Georgia Health News and the health and medical journalism graduate program at UGA Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, a partnership made possible by the Ford Foundation and Grady College.

Mechelle Goshe found the notes from the teacher in her 7-year-old son’s backpack, along with a jumble of failed tests and crumpled assignments. The teacher wrote that Edward couldn’t get any work done in class because he was either withdrawn in a corner or bouncing off the walls.

“He was driven by a motor,” Goshe recalled – a motor that neither she nor the teacher knew how to regulate.

Goshe was on a tight budget, but she found a psychiatrist who accepted Medicaid. The psychiatrist diagnosed Edward with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. A prescription for Adderall helped, but Goshe yearned for more.

She felt that her son needed to practice interacting with his peers in a place where he wouldn’t be labeled a “troubled youth.” She was looking for a community of understanding parents.

“When you’re positive, your kid is positive, and if you’re negative, they’re negative,” Goshe said recently. But all this happened 12 years ago, and she and her son needed services that simply didn’t exist in Albany back then. Prescription drugs and periodic visits to a psychiatrist were the best care available at the time.

Life got better in 2012. The Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities funded a new center to help school-age children and youths with ADHD, depression or anxiety disorders, or other serious mental health problems.

The Aspire Clubhouse sits behind a pet store off a busy thoroughfare not far from downtown Albany, the urban nucleus of a mostly rural part of the state. The clubhouse is open after school and into the evening and staffed by professionals and lay helpers who work for Aspire Behavioral Health, a nonprofit that provides mental health, addictive disease and developmental disability services to southwest Georgia.

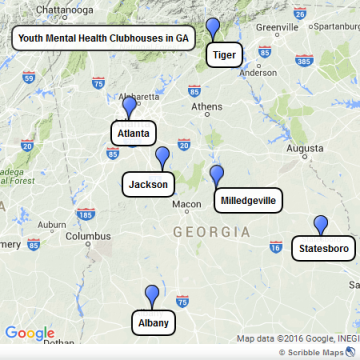

Today, it is one of six youth mental health clubhouses in Georgia (see the map).

Funding is always an issue

Generally speaking, programs to serve Georgia children with mental illness don’t get much state funding, said Ellyn Jeager of the Georgia chapter of Mental Health America. That’s especially true for more vulnerable populations, she said.

The Georgia General Assembly recently approved a committee on children’s mental health that will study the “conditions, needs, issues, and problems” of state resources for kids.

Jeager said she is hopeful that the state will allocate more resources to intervention programs like clubhouses. She said there is certainly much to be done.

“Where you see poverty, you see kids who don’t have access to resources,” she said, adding that children are often exposed to violent, traumatic events but don’t have a safe haven. “Everywhere needs a clubhouse,” she said.

Goshe and Edward applied for services as soon as the Aspire Clubhouse opened, and Goshe hasn’t really left since she walked in with her son four years ago. Although Edward cannot participate now that he has turned 19, she has joined the staff and is in charge of parent outreach.

She knows first-hand that parents need help coping when a child who receives a serious mental health diagnosis. This is especially important in a county where more than 60 percent of children live with one parent and 47 percent of families exist below the federal poverty line. Both numbers are nearly double the average for the state.

Many families in the area live out in the country, where access to transportation – not to mention health care – is limited.

Dougherty County, where Albany is located, ranks 154th among Georgia’s 159 counties in terms of overall health outcomes. The makeup of the clubhouse mirrors the rest of the county: Most of the students are African-American and come from low-income families. Given their financial circumstances, transportation is a persistent issue for them, as are inadequate housing and food insecurity.

“There are no other programs that will pick them up from school, give them a snack, help them with their homework and give them dinner,” Goshe said. “And that may be the only meal they get that day.”

Children and youths who qualify for mental health services typically come two or three afternoons a week for about three hours each time. Two hundred kids are enrolled in the program, and every day vans transport 40 to 60 of them from school to the clubhouse and then home. Children of elementary-school age come on some days, older kids on others.

They flood a bright space meant for children and young adults, where rows of computers and video game consoles co-habit with full bookshelves and musical instruments. A basketball court and playground beckon in an outdoor fenced yard.

Snacks come first, and then it’s straight to homework, followed by everything else.

Lessons on living in the world

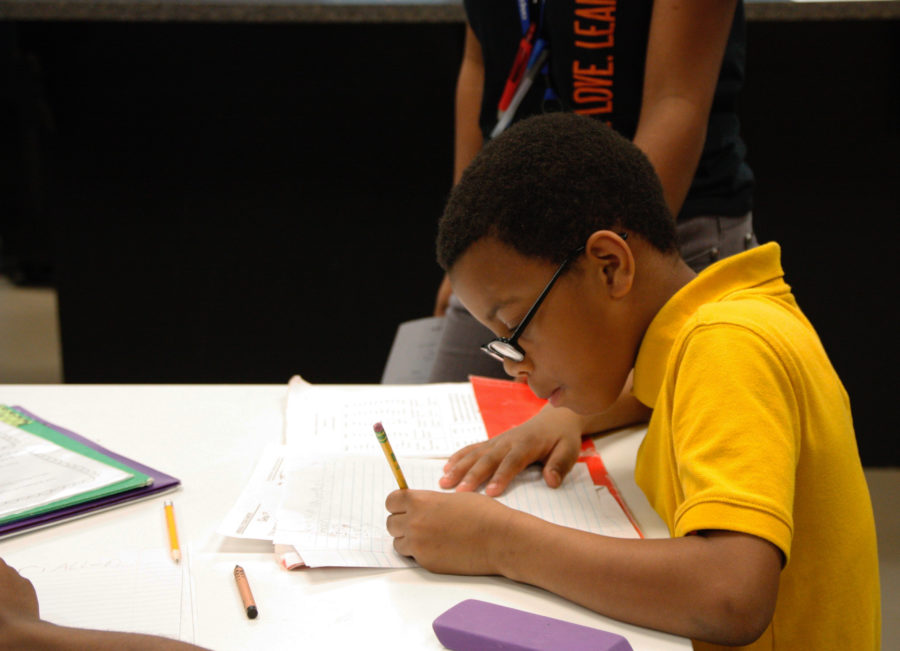

On a recent afternoon, Goshe helped a small group of elementary-school-age kids with their vocabulary practice and multiplication tables. They worked quietly together, while older children read to themselves nearby. The noise level was moderate and the vibe happy. Kids don’t dread this after-school program – they don’t want to leave.

About 1 of every 5 kids in the nation has some form of mental illness, according to the CDC. But some children are more likely to get help than others. Three-quarters of clubhouse participants were previously undiagnosed and untreated, according to director Lisa Spears.

“The youth that we work with just don’t have the resources that many of us did coming up,” said Spears, “so we try to put those resources in their hands.” This means connecting them not only with traditional psychiatric services and behavioral therapy, but also teaching them critical skills for living in society.

Physical activity includes everything from basketball to karate and yoga. For older kids, the clubhouse helps pay fees for SAT tests or driver’s license testing.

Without the clubhouse, these kids would be at home by themselves or out in the streets.

On a recent day, while Goshe tutored, Patrick Smith gathered fourth- and fifth-graders for group activity in the exercise room. This session was about leadership and personal responsibility, part of the clubhouse’s life skills curriculum.

“Leaders realize they are drivers, not passengers,” said Smith, who heads after-school programs at the clubhouse. “What does that mean?”

Some kids stared back at Smith blankly, but a few shouted in reply, “Take responsibility!” The goal, he reminded them, is to “aspire” to something, to keep reaching for a better life.

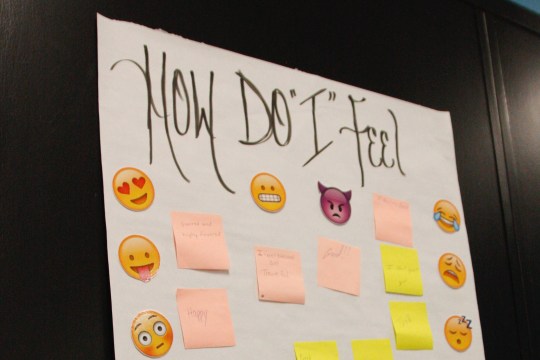

Children with serious mental health disorders can’t be helped if the stigma surrounding their problems keeps their families from reaching out on their behalf. “Most people aren’t educated about [mental illness] and parents are perplexed by it,” said Spears, who is a licensed psychotherapist.

Aspire staffers work with schools, law enforcement and the juvenile courts to make sure that officials and the public know about the clubhouse, which also serves as a children’s psychiatric outpatient provider during the day, with a full-time psychiatrist and nurse on hand.

“Many of our kids have struggled with anger, forgiveness and defensiveness because they’ve dealt with stigma or come from a history of family violence,” said Spears.

It’s often difficult for adults to recognize that their families are in trouble. “A lot of people are in denial that they might need help,” Goshe said about parents she interacts with. “There’s more we can do as a whole community, so people don’t fall through the cracks.”

The CDC reports that about half of children with serious mental health issues go untreated. Among children with certain disorders, such as anxiety, only about a third get treated.

But this doesn’t have to be the case. “We see potential in these kids and are not willing to give up on working to change a broken system,” said Spears. “These kids have a future, and it can be a creative one.”

Edward Goshe is a case in point: He’s graduating from high school this month and starts college at Albany Tech in the fall.

Young people who go through clubhouse programs grow into different people, and it can be hard to even recognize them as the socially awkward, misbehaving kids who came in four years ago, said Goshe. Her biggest hope is that behavioral and preventive services like the clubhouse continue to grow throughout the state.

Erica Hensley is a health and medical journalism graduate student at UGA’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. She graduated from the University of Southern California in 2008 with degrees in political science and print journalism, then freelanced and managed an independent bookstore in Atlanta before pursuing a master’s degree to focus on disparities in mental health care resources.