Joe Drogan’s polio story began at a very early age. So early, in fact, that he doesn’t even remember the moment. He was 10 months old.

“My first recollections of being somehow different from the other kids didn’t begin until a good bit later,” he said.

Drogan does remember the twice-a-year visits to a Shriners outpatient clinic in Massachusetts.

“How I dreaded” those trips, recalled Drogan, who now lives in Dawsonville.

Today, at 65, he’s able to appreciate what the Shriners did for him all those years ago. They paid for operations that his family never could have afforded. But as a child, he just wanted to be like the other kids.

“What bothered me most about that experience was it was becoming impossible for me to believe there was nothing really wrong with me,’’ Drogan said recently. “I was being forced to accept the reality of the situation.”

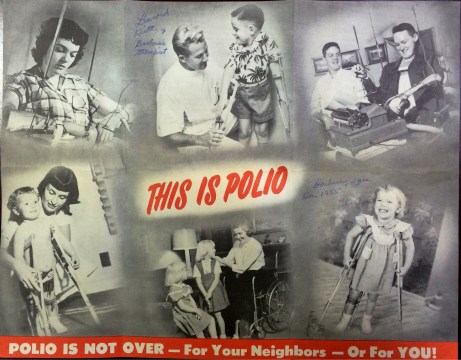

Polio, or poliomyelitis, is a crippling and potentially deadly infectious disease caused by a virus. The virus can invade a person’s brain and spinal cord, causing paralysis. It was once known as “infantile paralysis.”

In the late 1940s and early ’50s, polio outbreaks in the United States crippled an average of more than 35,000 people each year. Most victims were children. The disease terrified many American parents, who feared the worst whenever a child ran a slight fever or complained of a body ache.

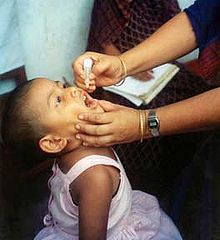

Things have changed dramatically since then. Thanks to polio vaccines, the first of which became available in 1955, polio has been eliminated in the United States, according to the CDC. But the effects of the disease are still being felt.

Drogan recovered from polio, but today he suffers from typical post-polio symptoms — occasional severe fatigue with increased muscle weakness. “I do have pain in my non-polio shoulder caused by overuse to compensate for the right shoulder and arm weakness from polio.” Some paralysis remains in his right arm. He has endured three surgeries to his thumb, shoulder and forearm.

At about age 50, he began to have additional issues. He was in an accident that left him with a severe concussion. “During the recuperation period it became evident I wasn’t recovering the way I should,” Drogan said.

Post-polio syndrome had entered the picture.

Although not life-threatening, post-polio syndrome, or PPS, is a troubling condition. It can include muscle weakness (at times severe), fatigue (mental as well as physical) and joint pain.

Post-polio patients will notice the syndrome’s effect about 15 to 40 years after their initial polio infection, according to the National Institutes of Health. NIH says the exact incidence and prevalence are unknown, but researchers estimate that post-polio syndrome affects 25 percent to 40 percent of polio survivors.

“. . . Just about the time we [polio survivors] think we’ve succeeded in having a good life despite polio, we are hit with this ‘I’m baaack’ type of thing,” explained Drogan.

Because polio itself has faded from the public consciousness in recent decades, post-polio syndrome is relatively obscure. Few people talk about it unless it’s part of their personal experience.

Once a month, Drogan and other people with that experience get together, when the Atlanta Post-Polio Association (APPA) holds a gathering. These events are held at the Shepherd Center, one of the nation’s leading facilities for physical rehabilitation.

In an environment of camaraderie, PPS sufferers share their feelings about the issues they confront every day. There’s a lot of laughter, mixed with serious conversations about everything from finding the right physician to taking the proper approach to exercise.

A career cut short

Barbara Mayer was living in Phoenix when polio came into her life. She was 22 months old.

Mayer had to wear two long leg braces and use crutches. But one of the braces was removed after only four months. Eventually, after extensive therapy, she recovered.

“I did well,” said Mayer, now 62 and living in Gainesville.

She noted that her polio diagnosis in the early 1950s hit her family hard. “It took an emotional toll on my parents,” she said, but added, “I was too young to know.”

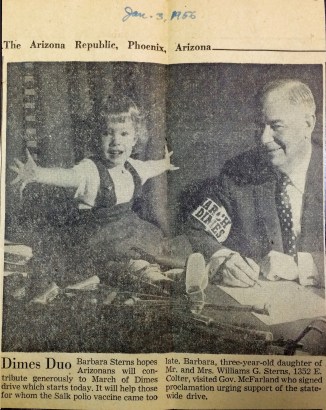

She was a March of Dimes poster child for polio, with a winning smile that got her photographed with Arizona’s governor at the time.

Later in life, Mayer’s determination led her to a career in nursing. As an RN, she was able to work and teach and help people, just as medical personnel had once helped her.

But post-polio syndrome began to make her work more difficult. She said that by 2013, her overall fatigue and increased weakness forced her to quit the nursing field.

Dealing with clueless people

Polio was once a very high-profile disease. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who died in 1945, lost the use of his legs to it. (Roosevelt was a pivotal figure in expanding efforts to help people with disabilities.)

Today, decades after polio was beaten in the United States, the public memory of it has faded. Many young people know next to nothing about it. This level of ignorance can be exasperating to older people currently coping with post-polio syndrome.

One attendee at a recent monthly meeting at the Shepherd Center said today’s generation just doesn’t understand how anyone could have had polio.

Another attendee said, “You tell people you had polio, and they want to know why you didn’t get vaccinated.” It apparently does not occur to some people that there was once a time when the polio vaccine did not exist.

Cheryl Hollis, another attendee at the meeting, said that when people are curious about her post-polio limp, she has a ready retort: “It’s just an old football injury.”

Understanding the condition

Unlike polio itself, post-polio syndrome is not contagious. Only polio survivors can get it, and not all of them.

It is estimated that there are currently 640,000 survivors of polio in the United States. Based on the percentages cited earlier, as many as 128,000 to 256,000 of these people may have PPS.

Wayne Nichols, who recently attended his first PPS meeting, said he had been diagnosed with the condition not long before. The doctor who diagnosed him was Dr. Dale Strasser at Emory.

Nichols originally got polio at age 3, and he was cared for at Cook County Hospital in Chicago. The treatment required 90-minute car trips to the hospital, which was “a hardship for my parents,” says Nichols, now 65 and living in Buford. He has endured four surgeries in his lifetime.

“Dr. Strasser suggested this support group,” Nichols said.

The monthly meetings of the group serve several purposes. They are educational (especially about the late onset of post-polio syndrome) and supportive, and there is also a focus on advocacy.

Advocacy is a critical component of the group. That’s because members are concerned about the impression they make on uninformed people. They don’t want polio survivors to be misunderstood when they struggle with new symptoms. They don’t want PPS sufferers labeled as “chronic complainers,” or erroneously placed in the fibromyalgia category by inexperienced doctors.

PPS differs from other afflictions, and people who suffer from it need an in-depth understanding of why their bodies are weakening. It’s not just a collection of old-age aches and pains, the group members say. Almost all of them led very active lives until their conditions changed.

The members of the group suggest that today, physicians and nurses are not trained to recognize post-polio syndrome.

A neglected group?

Drogan said, “Around 40 or 50 years of age, we start running out of neurons that had been ‘picking up the slack’ for years.” He says that’s why exercise can cause great damage to PPS sufferers in later years.

According to Post-Polio Health International, polio survivors need not fear “killing off” nerve cells, but they do need to realize that the deterioration and possible death of some nerve cells may be a part of normal post-polio aging.

Exercise programs should be designed and supervised by physicians, physical therapists or other health care professionals who are familiar with the unique pathophysiology of post-polio syndrome.

With big outbreaks of polio well in the past, there are virtually no younger polio patients today, and therefore virtually no younger people who will eventually develop PPS. That’s good, of course, but it means that current PPS patients are an aging demographic whose numbers will only dwindle.

A group like that doesn’t get high priority from the medical establishment, activists say.

“There’s little research” being done on the condition, said Mayer. “The money isn’t going to post-polio syndrome patients.”

And an increased focus looks unlikely. “Eventually, we will all die off,” said Mayer. “Research dollars follow cancer and diabetes, where there’s much more profit to be made.”

Judi Kanne, a registered nurse and freelance writer, combines her nursing and journalism backgrounds to write about public health. She lives in Atlanta.