Jonathan Swanson decided in high school that he wanted to become a doctor. But he doesn’t credit this decision to his own intellectual journey or to his parents’ steering him toward medicine. He believes the decision was influenced by a higher power.

“I believe that God gives us specific talents and desires that we can use to honor Him,” said Swanson, “I know that this is my calling and I love it.”

Swanson, 25, is currently a second-year student at the Georgia Regents University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership in Athens.

The medical partnership has no written policy discouraging up-and-coming doctors from being open about their religion. But Dr. Barbara Schuster, dean of the partnership campus, said students are taught to be mindful of that openness and not impose their beliefs on anyone else.

“What we try to teach our students is that it is fine to have your own faith, it is not a problem at all,” Schuster said, “but just like in all areas of diversity, we have to honor not only our own diversity but other diversities as well.”

She said students must be especially careful not to impose their beliefs when dealing with patients.

Whereas some nations over the centuries have had official religions or been officially atheist, the U.S. Constitution requires religious freedom for everyone. But questions of where one person’s freedom ends and another’s begins can be tricky. Public and private institutions try to strike a balance.

Seeking guidance in his field

The intellectual demands and pressure of medical school can be overwhelming. To help ease this anxiety, Swanson attends a weekly Bible study that’s hosted by local physicians.

Medical Campus Outreach is a Christian-based organization of current and future health care providers. Swanson said the weekly gatherings with MCO are more personal for him than when he attends church services on Sundays, because he enjoys being able to both challenge his colleagues and learn from them.

“Learning all these different things through the Word with other people who are in the same season of life with you is very important,” Swanson said.

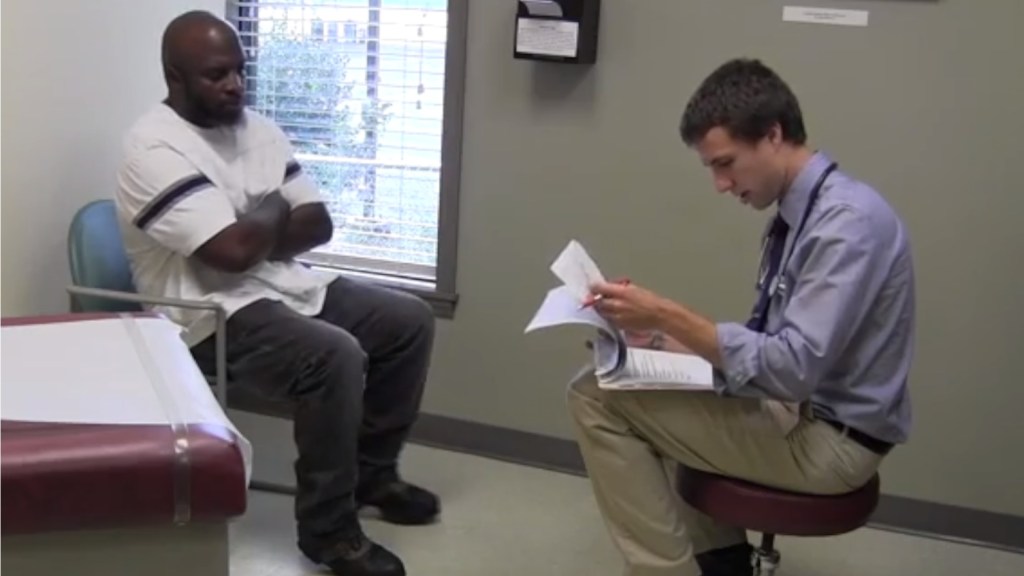

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DyStC8gABoc&feature=c4-overview&list=UUtg_U8UWdu_fZrvFlVwyXrA[/youtube]Although medical students don’t officially begin clinical training until their third year, some students seek volunteer opportunities that will expose them to patients during the first and second years. Swanson volunteers at Mercy Health Center, a faith-based free clinic in Athens. He said volunteering at Mercy has allowed him to witness some interplay between religion and medicine.

In addition to providing health care to qualified low-income patients, Mercy offers prayer to each of its patients. Swanson said offering prayer to patients demonstrates concern and an interpersonal connection.

“I would say nine times out of 10, if I told someone that I was going to pray for them, whether they believed the same thing I did or not, they would still really appreciate it,” he said.

While surveys have shown some decline in religious affiliation in the United States, they also show that a large majority of Americans are religious in some way.

A controversial topic

Hundreds of studies have examined the relationship between religion or spirituality and patient health. Harold Koenig, director of Duke University’s Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health, and his colleagues conducted original investigations and reviewed existing research by others in this area. He said this type of research creates conflict.

“There’s a lot of controversy depending on who you talk to, because everyone has their personal biases, and those biases are often very strong,” Koenig said.

After reviewing more than 500 studies, published from 1872 to 2010, Koenig’s team concluded that religion or spirituality has a significant impact on a patient’s health. Koenig said he believes the effects of religion or spirituality on patient health are beneficial at best and harmless at worst.

“I would say that there is a lot more research suggesting that it has beneficial effects than that it has no effect or a negative effect,” Koenig said. “But again you have to look at the research yourself, you have to look at the evidence.”

Some of the data are contradictory.

In one study, published in the Journal of Behavioral Medicine, researchers interviewed 177 adult cardiac patients, two weeks before their heart surgery. They found that patients who prayed more before the surgery experienced fewer complications after the surgery.

A larger study, published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, surveyed more than 2,000 adult cancer survivors in the U.S. The study found that 69 percent of those surveyed confirmed they had prayed for their own health. However, those who prayed less or not at all reported a better health status more often than those who prayed more.

Koenig said more physicians should consider spirituality when providing care to patients.

“This is something that is being more and more valued and recognized, [because] whether the physician is religious or not . . . doesn’t matter,” he said. “It mainly matters because it’s the patient that’s religious.”

Swanson said he hopes his personal faith will shape how he treats his patients and how they perceive him.

“Being a doctor is a pretty honorable position. People look up to you, and it’s easy for . . . [physicians] to get giant egos because of that,” he said. “If Jesus is still your example for how to be, then it’s humbling to use this as an opportunity to serve others.”

April Bailey is pursuing a master’s degree in health and medical journalism at the University of Georgia. She currently holds a bachelor’s degree in print journalism from Middle Tennessee State University.