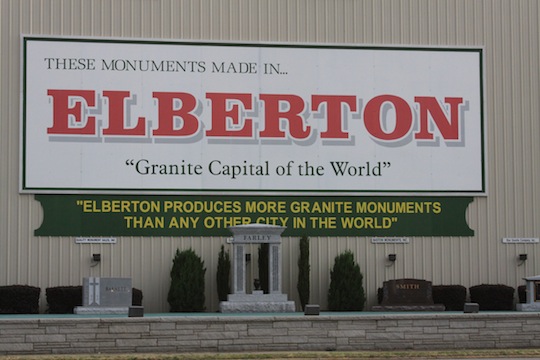

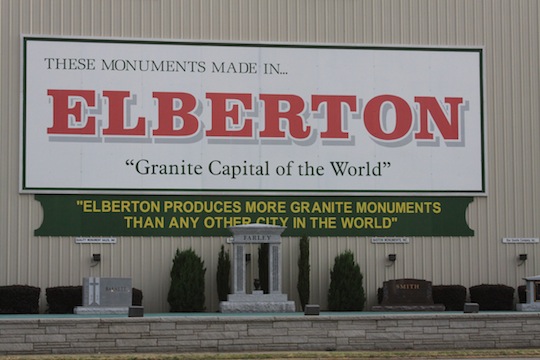

Elberton, Ga. — The public square here boasts an unlikely display: tombstones.

Above them, a billboard proclaims Elberton as ”The Granite Capital of the World.” But the industry that put this small town on the map has been linked to illnesses, and premature deaths, of many workers.

About 1,800 people, nearly one-third of Elberton’s workforce, are employed in its 45 quarries and 150 manufacturing sheds. Muscling heavy slabs of granite presents obvious risks for injury. The job of cutting and finishing granite into permanent markers appears safer, but in fact poses a more insidious hazard — silica dust.

Bobby Lee Smith has firsthand experience with both. A lifetime of cutting granite has left him with visible and invisible scars and many stories about friends who fell victim to the slow scourge of pulmonary disease.

Now 72 and retired, Smith cut granite at Dixie Granite, J&B Granite, and Harmony Blue Granite in Elberton, as well as other firms. For a time he ventured north to work at the famous Rock of Ages Quarries in Barre, Vt. He also worked in several “bootleg” sheds that are out of business now.

In the early 1990s, a heavy slab of granite fell on Smith’s right leg. He suffered a complex fracture, and when the leg healed it was several inches shorter than his left.

After the accident, Smith suffered from neck pain and difficulty in walking, which made it impossible for him to hold a full-time job. He retired in 2008 after nearly 50 years in the granite industry.

Retirement did little to ease Smith’s aches and pains. His daughter, Amanda Evans, recalls countless health complaints from her father and a series of treatments that didn’t work.

“He just kept saying his shoulder blades hurt,” said Evans, a nurse at Hart Care Center Nursing Home in Hartwell. “We thought it was arthritis.”

Then Smith experienced pain in his knees, for which he received cortisone shots in the summer of 2010. Shortly thereafter, things fell apart.

“He basically went paralyzed from his feet all the way up,” said Evans.

A surprising discovery

At that point, Smith could no longer urinate. His family took him to a urologist, who could find nothing wrong. Smith’s wife, Sherry, began catheterizing him at home.

A few days after the urologist visit, Sherry Smith called her daughter for help. Her husband, a broad-set man, could no longer walk and had become so feverish — presumably from bladder infection — that he was “talking crazy,” said Evans.

Evans rushed over to her parents’ home. Then she acted on a nurse’s hunch.

“I listened to his lungs,” she said, “His lungs were all congested.”

Evans drove her father to Athens Regional Hospital, where tests revealed that carbon dioxide levels in his blood were “extremely high,” she said.

Smith was admitted to the hospital’s intensive care unit and diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The diagnosis was unexpected, because most COPD patients have a history of smoking.

“I did not smoke,” said Smith, “I drank and all that, but I never smoked.”

The term COPD refers to both chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Nonsmokers like Smith account for less than 20 percent of people with this disease.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health estimates that almost 2 million workers in the United States are regularly exposed to silica dust. Most work in steel, construction, mining and related jobs.

Silicon is one of the most common elements on Earth. It’s abundant in soil, and ordinarily it’s harmless. But when silicon-rich stone, such as granite, is cut or polished, the work generates dust fine enough to be inhaled. The dust can build up in the lungs, resulting in silicosis. On a chest X-ray, silicosis appears as floating white material in the lungs.

“Many people with silicosis never have symptoms,” said Dr. Richard Schuster, an internal medicine specialist and professor of Health Policy and Management at the University of Georgia.

“Does silicosis do more than produce X-ray findings? It appears to be that the answer is yes, that silica dust is associated with the development of lung cancer in some people, and also chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” he said.

Silicosis, according to Schuster, exacerbates the symptoms of lung cancer and COPD, especially for people who smoke.

Safety methods are vital

Although he did not smoke, Smith admits that he occasionally put himself in harm’s way.

“It’s caused from not using your mask,” he said of silica dust inhalation. He wore his respirator mask “most of the time, unless it got hot.”

Along with respirator masks, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recommends that granite manufacturers use wet-cutting methods — sawing into granite only when water is running over it — to keep dust from flying.

According to Bill Hood, a representative of the Elberton Granite Association, most Elbert County granite sheds have used mainly wet-cutting methods for the past 30 years.

Yet dry-cutting methods are still used when granite blocks are joined together. To minimize dust inhalation, all the granite sheds in Elbert County are equipped with air vacuum systems and exhaust fans, Hood said.

In addition to the respirator masks required for dry cutters, all granite-finishing employees are required to wear earplugs, gloves, safety glasses and steel-toed shoes to prevent injury.

“The Elberton granite industry has become safer over the years, but the employee still has to take responsibility for working safely and using personal protection equipment as trained,” said Hood.

Added Tammy Parham, who owns J&B Granite in Elberton: “All my employees know that this could kill them.”

Grateful to be alive

Such awareness of the dangers was less common when Smith began cutting granite. And decades later, his family worried for his life.

“He looked just awful. He could not breathe,” recalled Evans. Doctors told Smith’s family that the buildup in his lungs was “like concrete.”

After he spent a night on a ventilator, Smith’s blood gas levels were normalized and he had turned a corner. He was walking and talking again, but he could remember nothing about the preceding few days.

In September 2010, Dr. Kimberly Walpert of Athens Neurology performed surgery on Smith to remove a mass on his spinal cord “the size of an orange.” Smith’s family believes the non-cancerous growth developed as a result of years of hammering granite.

Today, he moves carefully around his Elberton home, herding grandchildren from one room to the next. He uses a wheelchair to navigate the outside world because his balance is shaky.

“I thank Jesus every day for making me well,” said Smith, “and I think about my friends who died from silicosis, so many souls dead and gone.”

Smith’s younger brother is one of those souls. Barren Smith, also a granite cutter, passed away from lung cancer in 1999. He was 48.