High rates of obesity and infant mortality helped sink Georgia to the low end of a new state-by-state scorecard on children’s health.

Georgia ranked 43rd for child health among the states and the District of Columbia in the 2011 report card developed by the Commonwealth Fund. It was released Feb. 2.

The report analyzed 20 indicators of children’s health status in four areas: health care access and affordability; prevention and treatment; potential to lead healthy lives; and an “equity” measure based on income and racial and ethnic disparities.

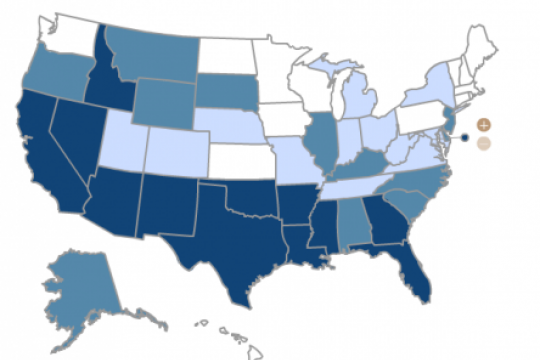

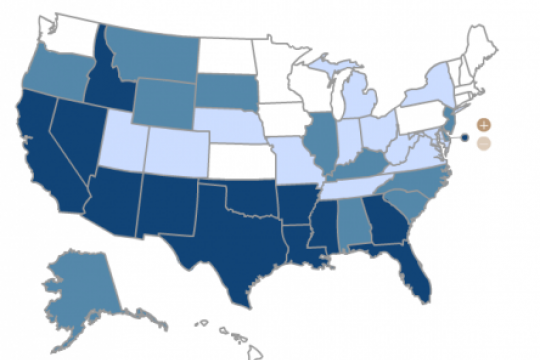

The scorecard showed that the Southeast and Southwest generally ranked in the bottom quarter of states. Exceptions were Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina and South Carolina.

The states in the southern regions “all have chronic issues of low incomes and poverty and health disparities,’’ said Kathleen Adams, an Emory University health policy professor. Rural areas of these states also have problems with access to medical care, she added.

The health indicators that affected Georgia’s placement included:

Georgia ranked 42nd in its infant mortality rate and 49th in the percentage of children ages 10 to 17 who are overweight or obese.

The state was 48th in the percentage of children needing mental health treatment or counseling who received mental health care in the past year. And Georgia was 47th in the percentage of children with special health care needs whose families received all necessary family support services.

Thousands lack coverage

Georgia was rated second among states in the percentage of children with health insurance whose coverage is adequate for their needs. But that’s a somewhat deceptive statistic, because the state was 42nd in the percentage of children who actually have health insurance.

“It’s not surprising that Georgia ranks so low on child health,’’ said Joann Yoon, associate policy director for child health at Voices for Georgia’s Children, an advocacy group. Yoon said an estimated 300,000 children lack insurance in the state, but that 193,000 of them qualify for government programs Medicaid or PeachCare but are not enrolled.

“Clearly, there’s a shared responsibility between government and community members to enroll and retain children in these programs,’’ Yoon said.

Government insurance programs helped children’s health overall, said the report from the Commonwealth Fund, a nonprofit health care research group based in New York.

“The study demonstrates how policies designed to maintain children’s health insurance and access to health care have helped children get the health care they need, especially in tough economic times,’’ said Cathy Schoen, Commonwealth Fund senior vice president.

Factors that have lowered Georgia’s child health rankings, including obesity, have become major concerns among health officials in the state.

Much of the obesity problem is linked to economics, among other factors, said Dr. Harry Heiman of Morehouse School of Medicine. “Those people with lower incomes, and lower access to healthy foods and green space, will have higher rates of obesity.’’

Those same financial gaps are evident in other health statistics of Georgia and the South, said Heiman, who is director of health policy for the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Atlanta-based medical school.

“When you have a more diverse population, and a poorer population, the needs are going to be greater at a time when budgets are being cut back,’’ Heiman said. “States in the South … will need more resources to care for that population because their needs are greater.’’

What’s being done now

Several new programs, meanwhile, are being implemented to improve Georgia children’s health.

The state has adopted an annual in-school assessment, measuring each student’s cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength, muscular endurance, flexibility and body composition. “There’s [currently] a lot of emphasis on CRTC scores, which may detract from the importance of physical activity during the school day,’’ Yoon said.

School districts in the state are offering students greater access to healthier menu items. For example, the Atlanta Falcons Youth Foundation is partnering with Sodexo-Jackmont and Georgia Organics to promote healthy lunch and breakfast menu items in the Atlanta Public Schools.

To reduce the number of low-birthweight babies, the state Department of Community Health has started a program that offers medical and family planning services for low-income women. The birthweight program has real promise, Emory’s Adams said.

And Georgia is making progress on teenage pregnancy. The state had one of the biggest drops nationally in its teen birthrates in 2009, the AJC reports.

Here’s the link to the Commonwealth Fund study. Click on the map, then click on Georgia to get all of the state’s statistics.