Brenda Goodman is senior news writer at WebMD. Andy Miller is CEO and editor of Georgia Health News.

Feb. 20, 2018 — A brown bat the size of a mouse with teeth like a stapler may or may not have bitten Tamara Davis in Georgia. But it certainly took a bite out of her bank account, generating hospital bills of more than $17,000.

The groundhog that charged Linda Gallagher in Maryland while she was gardening last summer caused her to rack up more than $11,000 in charges.

A fox that sank its teeth into Crystal Edwards in North Carolina last year could end up costing her more than $22,000.

Doctors agreed that all three women needed a series of shots to protect them from the deadliest virus known to medicine — rabies. Once symptoms begin, the disease is almost always fatal.

The treatment regimen for rabies was first developed in the late 1800s, and it hasn’t changed much over the last 100 years.

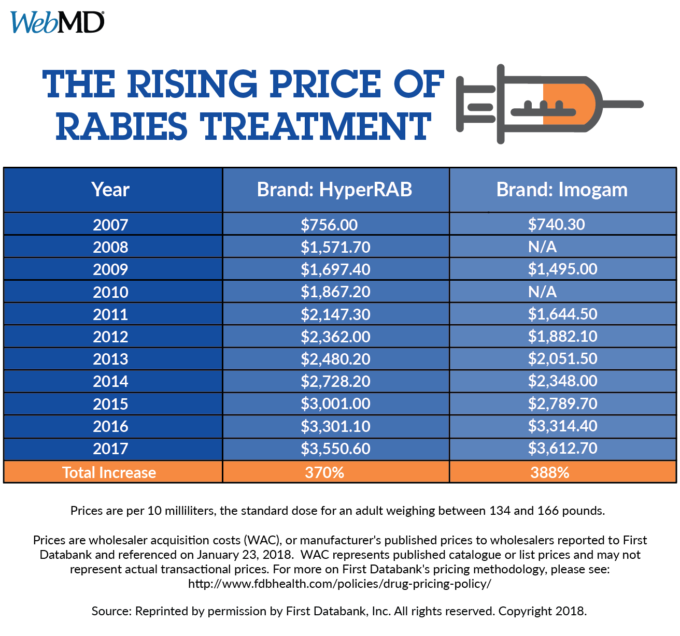

But the price of survival has gone up rather dramatically — nearly 400% over the last decade for those shots.

That rise is part of the reason why people who have insurance coverage may be stuck with hundreds of dollars in out-of-pocket costs, while the uninsured and underinsured often face thousands of dollars in medical bills.

In 2007, for example, vaccine maker Sanofi Pasteur charged an average wholesale cost of $740 per 10 milliliters for its Imogam immunoglobulin, a purified blood product that is the most expensive part of the rabies treatment. Ten milliliters is the amount used for an adult who weighs between 134 and 166 pounds.

By 2017, the company charged $3,612 for the same dose, an increase of 388% over the last decade, according to First Databank, a company that tracks pharmaceutical costs.

HyperRAB, the other brand of immunoglobulin on the market, has seen price increases of 370% over the last decade.

The CDC estimates that as many as 50,000 people in the U.S need this regimen to guard against rabies each year.

The second part of the treatment, a rabies vaccine, isn’t cheap either. It wholesales for about $260 a dose, and people need several during the treatment.

In a statement, Sanofi, the company that sells Imogam, said: “The cost of our rabies immunoglobulin takes into account the extensive quality assurance required for human plasma-based products, the uniqueness of its manufacturing and increased costs related to non-Sanofi production processes.”

Grifols, the manufacturer of HyperRAB, declined to comment on the price increase.

An old treatment gets new prices

The rabies virus pierces nerve cells with a bullet-shaped outer shell. It then travels along their long tentacle-like axons to the spinal cord, where it speeds to the brain. Once there, it begins to multiply inside brain cells, destroying them and shutting the body down, organ by organ.

In the late 1800s, scientists realized that it might be possible to defend people against rabies by giving them repeated vaccine doses along with the blood of someone who’d developed an immune response to the virus because they had been vaccinated against it.

That treatment — with a purified blood product called human rabies immunoglobulin, combined with repeated doses of rabies vaccine — is still what doctors use to protect people today. When given soon after exposure, these shots always work.

“This regimen has never, never, since the 1970s in America, failed. You’ve got an ironclad guarantee,” says Rodney Willoughby, MD, a pediatrician and rabies expert at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

To make the treatment, drug companies have to recruit donors and then “professionally immunize” them with the vaccine against rabies. Those people then have their blood drawn and purified to make the immunoglobulin, Willoughby says. The drug companies pay these people, who are human antibody factories. It’s a costly process.

In early 2017, Sanofi pledged to new pricing for all its products that would keep any rises in cost in line with growth projections for medical inflation from the federal government.

But the price of the shots is only part of the picture.

Whether a patient ends up with crippling medical bills depends on the state where they get it, the setting — a doctor’s office or hospital ER — and whether or not they have insurance.

Public aid for rabies treatment has waned

In some states, like New York, Florida, and Texas, state and county health departments help control the cost of the shots, either by giving them to patients at cost or picking up any part of the bill that’s not covered by insurance.

But this kind of help is becoming harder to find. WebMD and Georgia Health News surveyed health departments in all 50 states and learned that nearly all have dropped this kind of assistance because it has become too expensive or because they don’t offer patient care through a clinic.

Alaska, for example, stopped offering free rabies treatment in 2014 because it became too expensive. Wyoming also used to cover the cost of rabies treatment, but funding for that program ran out in 2010, says Karl Musgrave, DVM, the state public health veterinarian.

In most areas, the only place that keeps these pricey shots in stock is a hospital emergency room. Patients treated in an ER can expect the wholesale cost of the treatment to be marked up 2 to 3 times, and in some cases dramatically more than that.

“I was just stunned when the bill came in, just stunned,” said Michael Gallagher. He got an $11,000 bill after a groundhog attacked his wife while she gardened in their backyard last summer in Forest Hill, MD.

Linda Gallagher was kneeling in some tall grass when she felt movement near her foot. She wasn’t sure — things were happening fast — but she thought the groundhog bit her. Then it kept coming. She leapt up and ran for their nearby pool, but the groundhog jumped in after her. She swam to the other side and ran screaming toward the sunroom door. Mike heard her and let her in.

“She was cut up pretty good,” he says. They first called animal control, and then they headed to an emergency room near their home. They never caught the groundhog.

She got an immunoglobulin shot near the site of the wound, along with doses of the rabies vaccine.

The charges for that first visit totaled nearly $6,000.

“I called the hospital up and I said ‘what’s this?’ I have a charge from the pharmacy that was 5,000 bucks. I said, ‘You’re going to charge me that much money for a rabies shot?’ ” he says.

With more doses of the vaccine came more bills. Fortunately, Gallagher was paying for a COBRA policy through his former employer. But even with insurance, his out-of-pocket costs totaled more than $2,000.

“When it’s life or death, I think the medical industry knows they’ve got you by the short ones, so to speak,” he says. “I’m just totally upset about it. I’m still upset.”

“How does anybody without any means afford health care today?”

Less insurance often means bigger bills

Tamara Davis is wondering the same thing. She found a bat clinging to a dish towel in her kitchen sink over the summer. A friend came over, wrapped it in a towel, and let it go outside, which was the wrong thing to do, as it turns out, because the bat couldn’t be tested to see if it carried the virus.

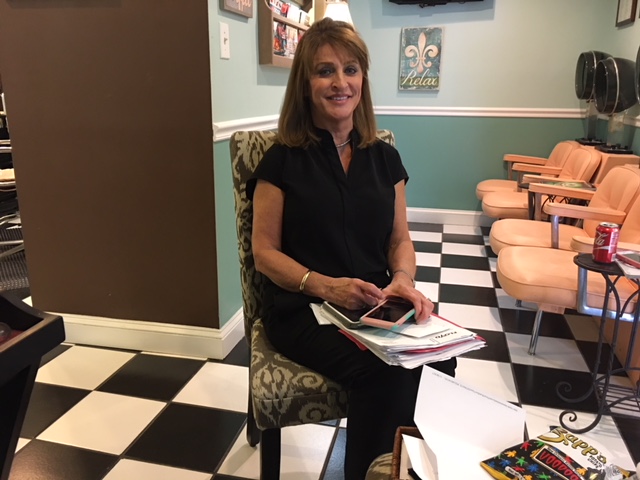

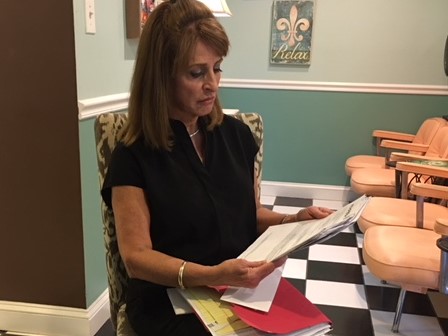

She reported the bat incident to her vet. “I was worried about my dog,” says Davis, 62, who runs a hair salon in Rome. There was no evidence that she or her husband had bite marks.

Bat bites, though, can be shallow and not easily noticed.

The vet told her to call the Georgia Poison Center or the Department of Public Health. And public health officials urged her, along with her husband, Randy, to get a rabies vaccine, she says.

Davis’ insurance plan ended a few days after she got her first round of shots. The total charges came to $17,000. She still owes Floyd Medical Center in Rome about $10,000.

Her husband, who was covered under Medicare, owes just $186 for his treatment, says a patient advocate for Davis.

“I had no idea what it was going to cost. Also, I had no choice. I had to get the shots,” Davis says.

In Georgia, the rabies shots typically aren’t carried in doctor’s offices or clinics, says Gaylord Lopez, PharmD, director of the Georgia Poison Center.

And when it is given in a hospital ER, the treatment can cost more.

Even though she was only getting shots at each visit, she was billed for different levels of emergency care for each of those three visits. For two visits, she was billed at a level that cost her more than $1,400 each. For another, she was billed $650. Davis is working with a patient advocate, Cindi Gatton, to dispute the charges.

The hospital, through spokesman Daniel Bevels, said it cannot comment on an individual patient’s case.

“We can say that the human rabies immune globulin and vaccine can be costly to both the patient and health care provider, regardless of where the treatment is offered,” he said in a statement.

The hospital has acknowledged that it improperly charged Davis for one of her ER visits and lowered that part of the bill, according to Gatton, Davis’ patient advocate.

Sanofi says it works with providers to help patients who can’t afford rabies treatment by reimbursing either the cost of the product or resupplying it to the hospital through a patient assistance program. In 2017, it said it supplied immunoglobulin to more than 110 patients and rabies vaccine to more than 220 at no charge.

None of the patients interviewed for this story said they had been offered this option, even after they struggled to pay their bills.

Floyd Medical Center agreed to help Davis apply for patient assistance after her advocate, Gatton, asked about the option.

Americans also pay some of the highest prices in the world for this treatment. Our high costs offset steep discounts drug makers give to poorer countries where rabies infections are more common, says Willoughby, the rabies expert at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin.

In the bizarre world of U.S. health care pricing, people who are the poorest and most vulnerable because they don’t have health insurance often get stuck with the highest bills because they don’t have anyone negotiating the price for them.

The bite that cost more than a year’s wages

That’s what happened to Crystal Edwards in Advance, NC. She was coming home with her husband, Todd, last June when a furry animal leapt off their front porch and brushed past them.

“I thought it was a cat,” she said.

It wasn’t. It was a fox, and it had rabies, which can make animals more aggressive than normal. It bit her ankle, leaving two puncture wounds. It kept coming after her, even after she ran into the house to get away from it.

Todd shot it to get it away from her. The health department tested it and found it had rabies.

Crystal went to the ER at nearby Novant Health Clemmons Medical Center. She got eight shots, including two shots of immunoglobulin — one into each puncture wound on her leg. The bill? $20,000.

“That was just one round,” she said. After two more visits, she got two more bills, which added another $2,000.

The total is more than she made last year as a waitress.

To make their financial picture even worse, Crystal says she lost her job because she missed so many shifts getting her shots and dealing with their side effects, which she described as feeling like a really bad case of the flu after every round.

Novant confirmed its charges and said it automatically knocked the cost of her bill down by 30%, to $15,657, when it learned she didn’t have insurance.

It also said it tried to get her to apply for more financial help through the hospital, but she declined to get help filling out the application, even though it followed up continuously “over a period of several months.”

Crystal says the hospital never explained its financial assistance process or how it worked. She said the calls she received were collections calls, and she was afraid to answer them because she didn’t have the money to pay.

Instead, she and her husband have set up a GoFundMe page to try to raise the money themselves.

Crystal has since gotten another job.

After we made inquiries about her bill, the hospital said it “will still accept completion of the financial assistance application to determine if Ms. Edwards may be eligible for any other forms of assistance,” said April York, senior director of patient finance at Novant Health.

In North Carolina, the state health department will cover the cost of rabies treatment for people who fall below the federal poverty level. The Edwardses believe they may qualify, and they’re frustrated that it’s taken more than 6 months for anyone to offer them that help.

“This is ridiculous. No one plans to go out and get bit by a rabid animal,” Crystal says. “I think something like this should be free.”

Anna Kaltenboeck, program director at the Drug Pricing Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, says people who are uninsured end up being billed what’s called the rack rate, or the hospital’s list price, before any negotiated discounts.

Although a third brand of rabies treatment is coming on the market soon, the competition may not lower the cost of treatment. Last summer, the FDA approved Kedrab, which should be available in the U.S. this spring.

Kaltenboeck says because Medicare and insurance companies base their reimbursement rates on the cost of the medication, it usually benefits the hospital to buy the higher-priced product.

For example, Medicare reimburses at its negotiated rate plus 6%. If there are two drugs, one that costs $100 and one that costs $200, the hospital is going to make more money from the product that costs $200, Kaltenboeck says. So often, the one that costs the most has a perverse advantage over its competitors.

Kedrion, the company that makes Kedrab, declined to reveal what it will charge for the product.

Price may lead to delay in treatment

The high cost has caused some people to hesitate before getting the shots.

Randall Large didn’t start treatment until 8 days after he found a bat under his pillow in Wyoming.

Large, who was unemployed at the time, balked when doctors in the ER told him the shots could cost between $10,000 and $16,000, according to in the Jackson Hole Daily.

“Holy crap,” he told reporter Kylie Mohr. “I don’t have that kind of money. I’m already stuck with the situation of, ‘Do I have rabies?’ and now you’re telling me I pay this or I die?”

Large had health insurance but was told it wouldn’t cover the treatment unless he had visible bites, which he didn’t, or if the bat was tested and found to be rabid.

The more research he did, the more frantic he became. Everyone told him to get shots, but he hesitated.

Finally, after days of frantic searching, he found the bat outside his bedroom window, where he’d tossed it. It tested positive. Large rushed to the ER to start the shots, more than a week later.

“I basically put my life on the line,” Large told the newspaper. “It’s just a crazy amount of money. People can’t afford this.”

Bitten by an animal? What to do

If you’ve had an encounter with an animal you think might have rabies, call your local health department.

They can help you figure out whether you really need the shots.

In Seattle’s King County, a 2015 study by the health department found that unneeded rabies treatment was given in about half of the cases it reviewed.

That’s because people often get it when they’ve been bitten by animals that have a low risk for carrying the virus, like pet dogs.

“Rabies is a very scary disease. When people hear the word, they want to get the shots anyway,” says Meagan Kay, DVM, regional health administrator for the King County Department of Health.

Getting the health department to sign off on treatment is required in some states, and even when it’s not, your insurance may require it.

“If it’s not recommended by the department of health, oftentimes insurance won’t cover it,” Kay says.

Some health departments also have programs that allow them to cover the cost of the shots if you can’t afford them and don’t have insurance.

If your state or county doesn’t offer financial help, check with your primary care doctor to see if she would be willing to order them for you. Getting the shots at a doctor’s office avoids costly facility fees charged by hospitals, which can add thousands of dollars to the bill.

If you do need them, and the ER is the only place that offers them, seek out the hospital’s financial counselors, who should be able to help you apply for aid from the drug company’s patient assistance program or other sources.

SOURCES:

Tamara Davis, needed rabies treatment, Rome, GA.

Mike Gallagher, had high bills from his wife’s rabies treatment, Forest Hill, MD.

Crystal Edwards, had high bills from rabies treatment, Advance, NC.

Rodney Willoughby, MD, pediatrician; infectious disease specialist, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Anna Kaltenboeck, program director, Drug Pricing Lab, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City.

April York, senior director of patient finance, Novant Health, Winston-Salem, NC.

Daniel Bevels, hospital spokesman, Floyd Medical Center, Rome, GA.

Karl Musgrave, DVM, state public health veterinarian, Wyoming Department of Health, Cheyenne.

Louisa Castrodale, DVM, veterinary epidemiologist, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Anchorage.

Meagan Kay, DVM, regional health administrator, King County Department of Health, Seattle.

Cindi Gatton, private patient advocate.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1971.

Medical Microbiology, Ch. 61, Rhabdoviruses, 4th ed.

First Databank: Unit prices for HyperRAB and Imogam.

Marea Feinberg, public relations consultant, Sanofi Pasteur.