A new March of Dimes report card gives Georgia a “D’’ grade for its preterm birth rate, which rose last year to 11.2 percent from 10.8 percent.

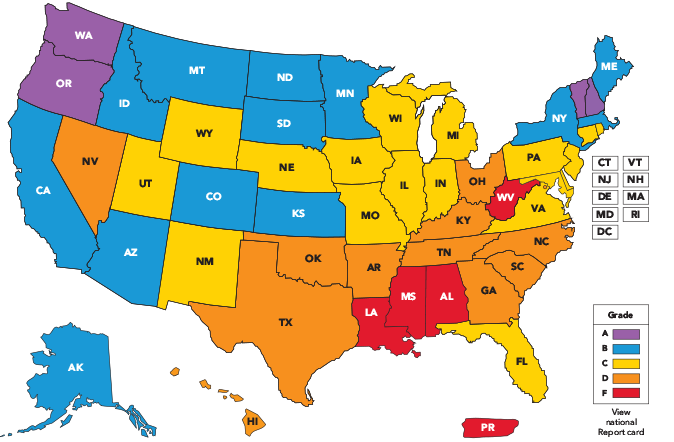

Ten other states and the District of Columbia also got a “D,’’ while four others and Puerto Rico received an “F” on the report card, issued Wednesday. Georgia’s grade stayed the same as in the previous March of Dimes report.

The nation’s rate of preterm birth also rose in 2016, to an average of 9.8 percent.

Nationally, more than 380,000 babies are born preterm, meaning too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy have elapsed.

Preterm birth is the largest contributor to infant death. And babies who survive an early birth often face serious and lifelong health problems, including breathing problems, jaundice, vision loss, cerebral palsy and intellectual delays. Preterm birth accounts for more than $26 billion annually in avoidable medical and societal costs, according to the National Academy of Medicine.

The March of Dimes report card also gave individual grades for the six Georgia counties with the most births in 2015.

DeKalb, Cobb and Gwinnett counties received “C’’ grades, though the latter two counties’ preterm birth rates worsened. Fulton and Clayton counties each received a “D,’’ and Chatham, with a 12 percent preterm birth rate, an “F,’’ though in each case, the county’s rate improved.

Neither Georgia nor the nation as a whole is “making a significant dent in the preterm birth rate,’’ said Dr. Denise Raynor, chair of the March of Dimes Georgia Maternal and Child Health Committee, and an Emory University School of Medicine professor emeritus.

Raynor said 39 weeks of pregnancy “is optimal for fetal development. There is more harm than people realize by delivering early.”

There’s no single, simple answer for the preterm birth increase, the Department of Public Health told GHN recently. “It’s a very complex interplay of factors,” said Dr. Lara Jacobson, director of health promotion at the state agency.

Those factors include the health of the pregnant woman and whether she has conditions such as hypertension or diabetes, Jacobson said.

If a woman has already had a preterm birth, she stands a greater chance of having one in the future.

Intervals between pregnancies also make a difference. Georgia mothers who have less than one year of spacing between delivery and the next pregnancy have a 12.3 percent preterm birth rate, Jacobson said.

Race is a significant factor as well.

The March of Dimes report found that in Georgia, the preterm birth rate among black women is 47 percent higher than the rate among all other women.

Raynor said that many African-American women feel chronic stress from financial problems and discrimination. The acute stress of a pregnancy adds to that burden, increasing the chances of having a premature baby or a low-birthweight baby.

“We have to make African-American people more aware that the preterm birth rate is a significant health problem for the black community,’’ she said.

Raynor added that access to obstetrical care is a problem in Georgia.

Longer distances to birthing hospitals can increase chances for preterm birth. But currently, only 46 of Georgia’s 159 counties have labor and delivery units, with about 75 hospitals in the state routinely delivering babies, according to the Georgia OB/GYN Society.

Many hospitals, especially in rural areas, have shuttered their birth units in the past two decades due to financial losses.

“There is a higher preterm birth rate overall in rural counties,’’ Jacobson said.

Other risk factors are alcohol consumption, drug use and smoking by pregnant women.

Advocacy by the March of Dimes has helped lower the rates of early elective deliveries, Raynor said.

The national report found the highest rates of preterm birth in the Deep South, Appalachia and the Rust Belt states of the Midwest.

“The 2017 March of Dimes Report Card demonstrates that moms and babies in this country face a higher risk of preterm birth based on race and ZIP code,” Stacey D Stewart, president of the March of Dimes, said in a statement. ”We see that preterm birth rates worsened in 43 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, and among all racial/ethnic groups. This is an unacceptable trend that requires immediate attention.”

Public Health, though, said Georgia has seen greater use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), which can help women to space their pregnancies better. Georgia Medicaid reimburses hospitals that implant LARCs. And Medicaid, which covers most births in Georgia, has stopped paying for early elective deliveries.

Hospitals also have launched programs to address risk factors during pregnancy, Public Health said.

And the March of Dimes cites the “Centering Pregnancy’’ initiative, a group prenatal program that combines health assessment, education and support.

The March of Dimes supports three Centering sites in Georgia: Upson (County) Regional Medical Center, Southern Crescent Women’s Health and Southwest Public Health District.