Sylvia Wright hails from a family that has a long tradition of white coats.

The Atlanta-based dermatologist and partner at Peachtree Dermatology Associates is a fourth-generation physician. For her, the white coat represents “the honor, the service and the commitment of practicing medicine.”

But Wright could be the last in her family to wear this signature garment for doctors. This semi-official uniform, which goes back a century, has come under attack in the United States and in some European countries.

Those who have declared war on the white coat come mainly from the infection control community. They argue that the coats, with their long, loose-fitting sleeves, are prone to be germ magnets.

“We know conclusively that the clothing worn by health care workers can be contaminated with harmful pathogens,” says Dr. Michael Edmond, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Iowa Hospital in Iowa City. “We have enough evidence to say it’s the right thing to get rid of the white coats.”

Several studies, including research by the World Health Organization (WHO), as well as by infectious disease experts in the United States, Britain and Israel, show that pathogens are easily transferred from surfaces to fabric, and from fabric to skin.

Studies have also confirmed that many of the microorganisms detected on white coats are antibiotic-resistant. They included Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is responsible for the most dangerous kind of hospital-acquired infections.

Another disturbing finding came in a 2014 survey, in which 57 percent of U.S. physicians admitted washing their coats only once a month, or even less frequently.

The weight of tradition

Historically, the white coat has had both a clinical and a cultural meaning. Until the late 19th century, surgeons used to wear black coats in the operating theater. A group of German doctors first traded the black coats for pristine lab whites.

After that, the white coat not only became a symbol of hygiene and purity, but also served the purpose of establishing physicians as scientists, and helping differentiate the barber from the surgeon, the quack from the doctor.

In the United States, many medical schools hold solemn white coat ceremonies, where aspiring doctors each receive their first coat as a symbolic act and rite of passage.

Therefore, it’s no surprise that the love for the white coat runs deep — and any attempt to get rid of it is met with tough resistance.

The American Medical Association in 2009 rejected a recommendation by some members to ban white coats, saying the issue needed further study. Many proponents of the white coat insist that research hasn’t sufficiently proved the transmission of bacteria and viruses from the coat to the patient.

The argument against white coats is built more on common sense than bulletproof scientific evidence, say those who want a change. “We do have strong plausibility that if we got rid of the coats, we’d see a reduction in infections,” says epidemiologist Edmond.

He remembers his personal “aha!” moment when, in 2007, the British National Health Service introduced a new dress code for health care workers, which marked the beginning of the end of the white coat in the United Kingdom. The policy was dubbed “bare-below-the-elbows” — meaning that the lower arms were to remain free of any fabric, jewelry or watches. The same regulation is in place in the Netherlands.

For Edmond, the bare-below-the-elbows policy “makes perfect sense.” Thorough hand washing — the most effective tactic against hospital-acquired infections — is much easier when the arms are not covered, he says.

That’s why, together with some colleagues around the United States, he launched a campaign against white coats.

He started wearing scrubs every day at the Virginia Commonwealth Hospital in Richmond, where he was employed at the time. He encouraged fellow physicians to do the same. Today, about 70 percent of the hospital’s health care workers are bare-below-the-elbows, and most doctors have shed their white coats.

Edmond plans to implement the same policy at the Iowa hospital where he now works, but admits that “those things take time.”

Actually, with the exception of operating rooms and critical care units, the traditional physician attire is still alive and well on the majority of U.S. hospitals wards, where a doctor in a white coat is a common sight. Also, many physicians in private practice wear long lab whites on top of their street clothes or scrubs.

Four major Atlanta hospital systems contacted for this article — Emory, Northside, Piedmont and WellStar — either declined to comment or did not respond to the inquiry.

The Georgia Hospital Association said it has not taken a position on the white coat. The Atlanta-based CDC, which has a strong influence on medical communities around the world, said in a written statement that “an important place for future research will be to establish the effect of a bare-below-the-elbows policy” on the transmission of pathogens and the incidence of hospital acquired infections.

Hygiene vs. psychology?

In some European countries, the debate is equally contentious. While Britain successfully phased out the white coat, the issue is still unsettled in Austria and Germany. Earlier this year, the private Asklepios hospital group, based in Germany, officially did away with long lab coats and replaced them with white, short-sleeved, collarless scrubs.

The German physicians’ union Marburger Bund asked Asklepios to rescind the ban. The Hamburg branch of the German medical association defended the white coat by citing its “undisputable placebo effect,” adding that “older patients with impaired hearing and vision are easily confused if they can’t immediately identify the doctor.”

Maybe that’s why Asklepios left a loophole by allowing physicians to wear white coats for consultations in their offices, for “public lectures, or in front of a camera.”

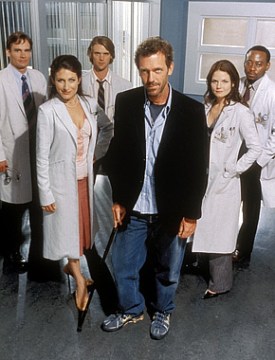

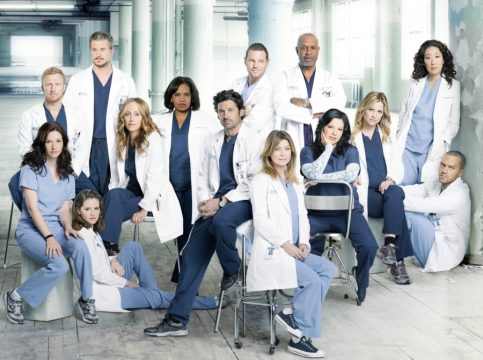

Perception counts, and cultural traditions run deep, especially in the medical community. The white coat has become a powerful symbol of doctors partly thanks to films and television programs going back many decades, including such shows as “E.R.,” “House” and “Grey’s Anatomy.’’

Several studies, the most recent by the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and published in JAMA Dermatology, found that many patients consider a doctor in a white coat to be more professional and trustworthy.

Edmond remains skeptical that physicians’ attire is a big deal to patients.

“My patients have never complained about my attire,” he says. “Most of them don’t care if I’m in pajamas. They just want me to help them.”

Edmond thinks that abandoning white coats will actually have a positive effect, eventually bring down barriers between patients and physicians, and also “help deconstruct hierarchy within the health care system.” And if someone along this way confuses him with a nurse, he says, “I don’t have a problem with that.”

The practical consideration

Fellow physician Sylvia Wright understands Edmond’s point, but does not totally agree with it. She says that like him, “I don’t need the white coat for my ego.” But she wears it for practical reasons, partly because it has large pockets offering enough room for a stethoscope, a prescription pad and a pen.

The coat also provides a level of protection “for both my clothing and my skin,” she says, adding that in her specialty, dermatology, she does a wide array of procedures. Blood or other bodily fluids, or harsh chemicals like surgical prep soap or certain acids, can get on her coat. If that happens, she says, “I can just take it off, pick up a new one and keep moving.”

While Wright doesn’t cling to the white coat, she thinks its distinctiveness can serve a purpose. She’s convinced that “stereotypes and biases still run deep [in society], even though it has changed tremendously in the past decades.” On the few occasions when she doesn’t wear her white coat in her practice, she says most people may not perceive her as a physician. “Because I’m a woman, and because I’m African-American.”

Aside from whatever biases that patients may or may not have, Wright says it’s a matter of professional efficiency in the health care field “that patients know clearly and without any doubt who they are dealing with — in my case: the doctor.” And for that, the white coat still serves as a sign of her professional status.

Wright adds, after a pause, that if researchers come up with an alternative garment that proves to be cleaner, more comfortable and better looking, she’d be willing to hang up her white coat for good — family tradition or not.

Katja Ridderbusch is an Atlanta-based foreign correspondent for German news media, including the national dailies “Die Welt” and “Der Tagesspiegel,” as well as German national public radio. She frequently reports about health care in the United States.