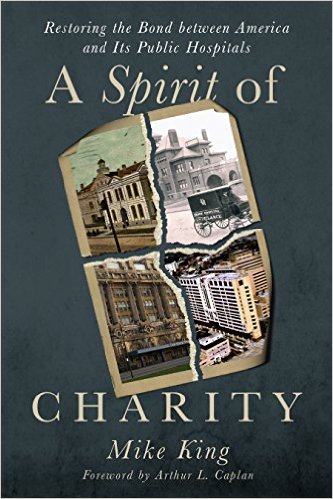

Mike King, a veteran health policy journalist who was a reporter, editor and editorial board member at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, is the author of “A Spirit of Charity: Restoring the Bond between America and Its Public Hospitals.” The book, available for purchase May 31, traces the history of the nation’s urban public hospitals through the prism of Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital, which in 1892 became Georgia’s largest publicly chartered charity institution.

The following excerpt, dealing with Grady’s near collapse in 2008, is adapted from the final chapter of the book. It also reports how a Grady leader helped the hospital make payroll — through his own checkbook.

Georgia Health News is publishing this excerpt with the author’s permission.

In 2008 the hospital was gushing red ink. It owed the two medical schools that provided its medical staff — Emory University and the Morehouse School of Medicine — more than $60 million. Pharmaceutical companies and vendors were complaining of late payments or no payment at all. And there was constant speculation within the staff that Grady would not meet the next payroll.

The Fulton-DeKalb Hospital Authority, which owned and operated Grady, had swept through four chief executive officers in just five years. It had just fired its fourth and installed the chairwoman of the authority, a state representative, as the hospital’s latest CEO. Despite no hospital administration experience — she was an attorney in a small practice by herself — the new CEO was rewarded with the same $600,000 yearly salary as the man who preceded her.

Grady had been through turmoil like this before, but nothing quite as bad.

As the hospital balanced on the edge, the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce and other civic groups assembled a task force that recommended day-to-day management of Grady be taken away from the hospital authority and turned over to a nonprofit management corporation, the way many other public hospitals and health systems have transformed themselves around the country over the last thirty years.

The head of the task force, former Georgia-Pacific CEO Pete Correll, spent months lobbying elected leaders at the state and local level. By turning Grady over to be run by an independent board — not political appointees — the hospital stood a good chance of restoring faith with the community, he said. If the hospital could reform its management, Correll promised to work toward raising $200 million in foundation and philanthropic grants so that Grady could modernize equipment and refurbish whole departments of the hospital while it was getting back on its financial feet.

His toughest job was in persuading black leaders in the two counties that it was a good plan and did not amount to “a white takeover” of Grady — a phrase commonly used to deride the plan. He concentrated his lobbying efforts on the powerful ministerial community in Atlanta that had rallied in the past against major reductions in Grady’s staff. Just a few years earlier, the ministers also fought hard against proposals that some of Grady’s low-income patients pay small, out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs. He enlisted the help of Michael Russell, CEO of H. J. Russell & Co., one of the largest black-owned construction companies in the country.

There was a lot of racial history to overcome. Many could still remember when the new hospital was built in 1958. Like the segregated hospitals that preceded it, they continued to call the new hospital “the Gradys,” because it was designed with segregated wings.

That changed with the Civil Rights Act and the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s. And by the mid-1990s, the hospital’s administration and the two-county authority that ran it was heavily dominated by African-Americans. The ministers and other black leaders in the region worried that the Chamber of Commerce folks now pushing the new governance plan would abandon Grady’s historic mission, or perhaps sell the hospital to a for-profit company.

Despite their misgivings, black leaders and the county commissions signed off on the plan. The authority retained ownership but the new governing board would run the hospital.

Grady, as it turned out, was in even worse shape than Pete Correll had imagined.

At one point, Correll, who chaired the new governing board, had to write a personal check for several million dollars just so the hospital could make its payroll — money that eventually was transferred as a gift to the hospital from him and his wife to improve cardiac care services.

The new board also found that thousands of “Grady cards” — essentially an ID that allowed the holder to get free care at Grady if they had paperwork to show their low-income status — were in the hands of people who never got their income verified. (A few Grady cards had even been provided to the families of elected public officials as a “courtesy.”)

The cards were created by the hospital authority years earlier to ensure only Fulton and DeKalb residents got free care at Grady. Indeed, hundreds of indigent patients a year are admitted to Grady, even though they live outside the two counties and Grady has no obligation to serve them

Even with the turmoil — or perhaps because of it — the money that Correll promised from local business and philanthropic leaders started to flow toward Grady Memorial.

The Robert W. Woodruff Foundation put up $200 million over four years. Much of that money from the city’s largest philanthropy went to improvements in the hospital’s information technology system, software for its imaging equipment, renovation of some semiprivate rooms to private rooms — all capital improvements Grady had delayed, some of them for longer than a decade, while it lurched from crisis to crisis.

The Marcus Foundation stepped up to provide $50 million, most of it toward improvements to Grady’s highest-profile services. Marcus money first went to rebuild the hospital’s trauma center as well as the stroke and neuroscience center. Both centers, which are named for Bernie Marcus, offer the most advanced specialty services in the state.

Marcus money went as well to reconstruct the rest of Grady’s entire emergency department, the hospital’s unofficial front door. Nearly three quarters of Grady’s admissions come through the emergency department. The emergency department sees more than 115,000 patients a year.

Still, it is important to remember that most of these improvements at Grady and other public hospitals are the result of private funding, not tax dollars from the state or local counties.

Indeed, the state continues to treat Grady as a local hospital that should not be Georgia’s problem.

Over the years, Georgia has provided a small amount of funding for some of Grady’s specialty services, such as its burn center, which takes in patients from all over north Georgia. The trauma center also gets some money to coordinate with a regional network of first responders and other hospitals.

But there is no mechanism at the state level in Georgia, as there is in some other states, to help finance public health and hospital services.

Instead, Georgia’s public hospitals essentially rely on two major sources of government funding to stay in business: Medicaid reimbursement, mostly limited to low-income pregnant women and children they treat, and local tax dollars to offset the estimated $1.5 billion they lose annually by treating adults with no means of paying their bills.

That’s the continuing challenge Grady faces. Unlike the business and philanthropic community in Atlanta, neither state nor local political leaders have stepped up to help the hospital become more financially secure.

Fulton and DeKalb counties have actually reduced funding for the hospital over the past two decades. In 2013 they provided just over $60 million toward Grady’s operations. That figure was about 8 percent of the hospital’s $764 million operating budget. (By comparison, the 1995 allocation from the two counties amounted to 25 percent of Grady’s operating budget.)

At the state level, the disinterest in appropriating money for indigent care isn’t directed specifically at Grady. It is mostly an ideological animosity toward the Affordable Care Act — or as it is always called in Georgia, Obamacare — and more specifically Medicaid. But the implications directly impact Grady, which could significantly reduce its charity load if more of its adult patients were covered by the federal-state program.

Unlike other nonexpansion states where governors and legislative leaders have at least considered the economic benefits of making Medicaid available to low-income, working adults, Georgia’s political leadership condemns the concept as too expensive and unworkable, although it has presented no substantive economic analysis to back up that claim.

At the height of the debate in 2013 over expansion, William Custer, a respected health policy and economics expert at Georgia State University, produced a detailed report that showed expanding Medicaid would generate more than 50,000 new jobs in Georgia and $65 billion in new economic activity. Moreover, at a cost of about 1 percent of the state’s $20 billion annual budget, expansion would infuse the state with an additional $276 million a year in new tax revenue, Custer reported — probably enough to offset the state’s additional spending on the program.

And then there was this assessment based on research published in the New England Journal of Medicine: Expansion would save the lives of approximately 1,179 people in Georgia each year, people who would otherwise die because they couldn’t afford the health care they need.

State leaders ignored these and other reports from nonpartisan sources about the wisdom of expansion. It was as if they didn’t exist.

When asked about them, the governor, insurance commissioner, and legislative leadership dismissed them as made-up numbers and the work of liberal advocacy groups who are out of touch with Georgia voters.

The attitude of Georgia’s elected leadership toward health care speaks volumes about the state’s priorities, and unfortunately in keeping with decades of outright animosity – among both Democrat and Republican administrations – toward federal programs designed to assist the poor.

In the same time frame Grady and public health advocates were clamoring for Medicaid expansion, the state and virtually all its elected leadership, including the mayor of Atlanta, were shuttling back and forth to Washington trying to secure federal funding to dredge the river channel leading to the Port of Savannah.

The port project was essential to Georgia’s economic development, the state’s leaders — including the governor, US senators, legislative leaders, and the congressional delegation — contended. Without federal money to support the project, vital new shipping business would go to ports elsewhere on the Eastern Seaboard. The state’s Republican officials chafed at what they saw as the Obama administration’s partisan disinterest in the project.

Yet many of these same elected officials have consistently rejected the $9 million a day that the ACA could be sending to the state — more than $30 billion over ten years — to expand Medicaid and make health care available to 500,000 to 600,000 residents who now go without it.

Conversely, the state is quick to tout what appears to be a very successful tax credit scheme that has attracted the television and movie-making business to the Peach State in recent years. For any production company that spends $500,000 or more making a movie or TV show in Georgia, the state offers up to a 30 percent tax credit on spending within the state. And if the company has little or no tax liability in the first place, it can sell its tax credit to another company. One recent estimate said the tax break generates about $6 billion in economic impact, most of it coming from nearly 80,000 jobs connected to studio and on-location productions.

Interestingly, the state chooses to proclaim these economic impact projections as gospel, while decrying the Medicaid projections as manufactured by advocacy groups.

The point is not that the state should give up its economic development projects like the Port of Savannah, or do away with the movie-industry tax credits. Now that the harsh impact of the recession is behind it, the state budget is showing healthy surpluses again.

The point is instead about priorities. All evidence indicates the state can more than afford to expand Medicaid and continue its economic development projects too. It simply isn’t a priority for state officials to do that. Not now, anyway.

Yet despite the state’s indifference, there is still cautious optimism at the 125-year-old hospital.

In 2013, Grady posted a net income of more than $19 million, according to financial documentation it provided to CMS. The CEO and other administrators reported in mid-2015 that it should close its most recent fiscal year with a $12 million to $16 million surplus — quite a different financial picture than what was happening a decade ago when Grady was headed toward a $50 million loss.

But while that bottom line may seem healthy, Grady’s operating expenses are north of $750 million annually.

All this means that Grady must continue to rely on local philanthropic support for capital improvements and to come up with new payment and delivery methods that — short of Medicaid expansion and a renewed commitment from local government — can help offset its costs for charity care. And it must do this while at the same time recognizing that it, and likely it alone, will still be responsible for providing crisis mental health care for the poor, comprehensive services for the uninsured with HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases, as well as emergency and acute-care treatment for immigrants who have taken up residence in our country without permission to do so.

Correll, who will leave Grady’s board in 2016, said he hopes to build a reserve fund that could be used in the event of an economic downturn or unexpected expenses in future years. He had a modest goal when the new governing board took over the hospital in 2008, he said.

“Grady will pay all its debts and never get to the crisis point that it was in when it almost had to close,” he said. Through a $20 million debt-forgiveness arrangement by Emory, and in its first years under new leadership, Grady finally repaid the two medical schools that had essentially served as its bank during the worst times. “We will make the hard decisions that need to be made before that would happen again,” Correll pledged.

To get a copy of the book:

and locally at: