While health care across rural Georgia has many shortcomings, Hancock County has languished at the more desperate end.

Located between Atlanta and Augusta, the county — named for the Founding Father who made history with his signature — has been marked by economic troubles for years. Its 9,400 residents have no hospital and no community physician, and roughly half the county’s children live in poverty.

But Hancock recently received new medical technology that officials hope will bring health care more easily to chronically ill residents. Georgia is a leader in telemedicine, and Hancock now is at the forefront through home patient visits.

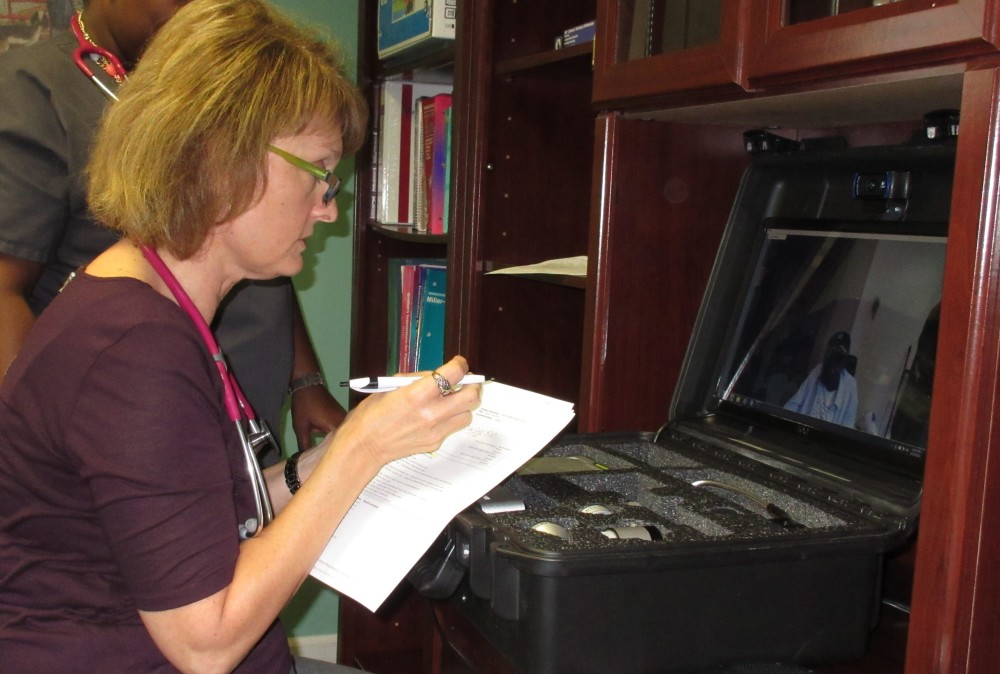

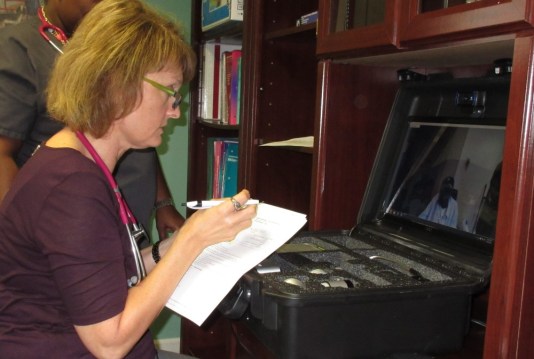

That new medical connection was on display recently at a Sparta clinic. Kemberly Smith, a nurse practitioner, faced a computer screen that sat inside a black luggage-like case. On a gray, drizzly October morning, she was talking to an elderly patient, David Smith, who is no relation to her. He was sitting in his apartment across town, but she could see him on the screen and talk to him.

It was a follow-up check-up for the 80-year-old man, and he could not get to the clinic in person. He had no transportation and no family nearby. He has relied on a power wheelchair since one of his legs was amputated, and getting to the clinic would have been difficult for him.

The Hancock County telemedicine setup is part of a special program coordinated by Mercer University School of Medicine in Macon, launched this summer with the aid of $100,000 in Gov. Nathan Deal’s budget.

(The Hancock project is separate from the state’s rural hospital stabilization program, which also is using telemedicine to help transform health care in four areas, and has a much bigger appropriation.)

Dr. Jean Sumner of the Mercer School of Medicine, who has spearheaded the Hancock initiative, said its goals include reducing the inappropriate use of emergency rooms for non-emergency situations and lowering the number of repeat hospitalizations. The program also aims to encourage and support the development of a primary care infrastructure.

“We feel it will make a difference,’’ said Sumner, who is from nearby Sandersville. She described Hancock as a “very poor, very sick county with almost no primary care access.”

The nearest hospitals are at least 25 miles away.

About 70 percent of the medically related 911 calls in the county are for non-emergencies, Sumner said.

Such structural challenges are widespread in rural Georgia health care. Four hospitals have closed since 2013 due to financial difficulties. Meanwhile, rural Georgians tend to have more chronic health conditions, and less health insurance, than residents of the state in general.

Many rural areas have a shortage of physicians and other primary care providers.

Hancock, with no doctors or hospital, looked to be as good a place as any to try something different. Thus came the purchases of the high-powered cameras and scopes for home patient visits, through the budget appropriation. Atlanta-based Grady Health System recently took over the ambulance service in Hancock, and the EMTs are trained in the use of the equipment when visiting patients.

“Other counties have been interested in this,’’ said Allison Williams of Community Health Care Systems, a federally qualified health center where Kemberly Smith works.

She is the only regular nurse practitioner at the clinic in Sparta. It’s now open five days a week, up from just Tuesdays and Thursdays. A doctor comes by about once a month, she said.

Many patients in the area have hypertension and other diseases, Smith said.

‘One more deep breath’

David Smith has vascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, along with hypertension. Shortly before this session with the nurse practitioner, he also had been suffering from a cold.

“Are you feeling any better?” Kemberly Smith asked the screen.

“Yes,’’ said David Smith.

Nurse practitioner Smith asked him about his medicines, his inhalers, the color of his sputum.

“I’ve been breathing pretty good,’’ he said.

“Have you had any chills or fever?”

“It’s much better, thank the Lord,’’ David Smith replied.

A nurse in David Smith’s apartment used a camera/scope to look into his ears and into his nostrils and throat. The images the device sent to the clinic showed up clear and crisp on Kemberly Smith’s screen. Then the nurse applied a Bluetooth stethoscope to the patient, for the nurse practitioner to listen to the heart and lungs.

Kemberly Smith clicked on a screen to show where she wanted the nurse to place the stethoscope on the patient’s body. “One more deep breath,” she told David Smith.

The electronic hookup for such remote examination sessions is made through a Wi-Fi connection. “In Hancock County, there are some areas that have no coverage,’’ said Sam Stephenson of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth. “We’ve made each ambulance its own hot spot. It will pull every available signal in the area,’’ he said.

Kemberly Smith wound up her “visit” with the patient and signed off.

“This is great I can see them this way,’’ she said. The camera can magnify high-definition images better than a regular office visit, she added.

She has been using the telemedicine hookup for a couple of months now.

Smith is a recent arrival in Hancock. When she came to the county to practice, she switched from specialty care to primary care. “I love being here,’’ she said. “I love challenges.”

The electronic home visits can cut down on the number of patients who have appointments scheduled but don’t show up, the nurse practitioner said. But she acknowledged, “I miss the in-person connection a little bit.”

Later, the patient, David Smith, greeted guests at his apartment. He said he liked the new method of getting a medical check-up because of the convenience.

“I’m glad I don’t have to go down there in the wheelchair,” he said.