Unlike city folks, who typically pay for water pumped by municipal utilities, many rural homeowners drink from their own wells without worrying about a bill.

Such wells are especially common in rural areas such as Morgan County, where roughly 3,700 of 6,538 households are connected to city water systems in Madison or Rutledge.

When private wells are properly installed and maintained, they are usually clean and reliable sources of water – but not always.

Because no state or federal regulations govern wells that have fewer than 15 connections (meters) serving fewer than 25 people, owners are not compelled to check their water for harmful bacteria or minerals.

As a result, most people who rely on these private wells “don’t know what they’re drinking,” according to the head of the University of Georgia’s water-testing laboratory, Uttam Saha.

The state Department of Public Health estimates that one in five Georgians drinks water from private wells — a figure that might surprise people in developed urban areas.

In Morgan County, about 2,838 households rely on private wells. Yet over the past 10 years, fewer than 600 samples from these wells have been sent to the University of Georgia’s Soil, Plant, and Water Analysis Lab (SPW) for testing, Saha said.

A survey conducted by UGA researchers found that Georgia had about 648,000 private wells in 2012. The SPW receives samples from about 23,000 of those wells every year, or roughly 3.5 percent.

Other organizations across the state conduct water tests – including private ones such as Dobbs Environmental in Covington and local public health departments – but the SPW is the only one with a statewide clientele.

Public Health officials say the Department of Natural Resources regulates non-public wells, and that the state does not require a permit process, testing or inspection for these water supplies.

Alarmingly, a 2010 study of samples from 1,075 private wells in Georgia found that 31 percent had bacterial contamination, said Chris Kumnick, land use program director at Public Health.

Larger, public systems and their water quality are overseen by DNR’s Environmental Protection Division.

Although there haven’t been any recent contamination threats in Morgan County, other parts of Georgia have had problems. Heavy rains in southwest Georgia last year prompted public health officials to advise residents to boil water from private wells before using it for drinking or brushing their teeth.

Some extremely toxic elements have been found in well water. If they reach high enough levels, they have the potential to undermine human health.

High levels of uranium — a naturally occurring element found at low levels in virtually all rock, soil, and water — were recently detected in Monroe County well water – a health risk because drinking water with high uranium levels increases the risk for kidney malfunction.

And in South Georgia last year, organic arsenic was found in private wells across 10 counties. Arsenic occurs naturally in the environment. At high levels, arsenic in water raises the risk for cancers of the kidneys, lungs, bladder and skin if ingested over a long period of time.

How was it dug?

There are two main types of household wells in Georgia. “Bored” wells are dug with an auger and are typically 24 to 30 inches in diameter and 10 to 30 feet deep. “Drilled” wells are much smaller in diameter and considerably deeper – usually 100 to 400 feet deep. They’re dug with a big rig that drills down and inserts casing as it penetrates.

An important difference between the two is that bored wells draw from water above bedrock and drilled wells tap into the aquifer, water below bedrock. Because bored wells draw from such a shallow reservoir of surface water, they’re far more vulnerable to contamination.

Bored wells are on the decline in Morgan County, according to Lee Lundy of Household Water Inc., which is based in Covington in nearby Newton County.

His company has been installing water-softening and filtering systems in Morgan County for generations. Twenty-eight years ago, according to its records, about 70 percent of the company’s clients had bored wells. Now that’s down to less than 10 percent.

“The drought a couple of years ago knocked most of them out,” Lundy said. “So we’ve seen that bored wells are a thing of the past – we hope.”

Saha of the UGA water-testing laboratory isn’t sure the balance has tipped quite as far toward drilled wells as Household’s records would indicate, but he acknowledges that his organization may be meeting a disproportionate number of householders with shallower, more trouble-prone bored wells.

Most well owners bring in a sample only “when they have some reason or some concern,” said Saha. People with drilled wells may be less likely to worry.

What’s in your water?

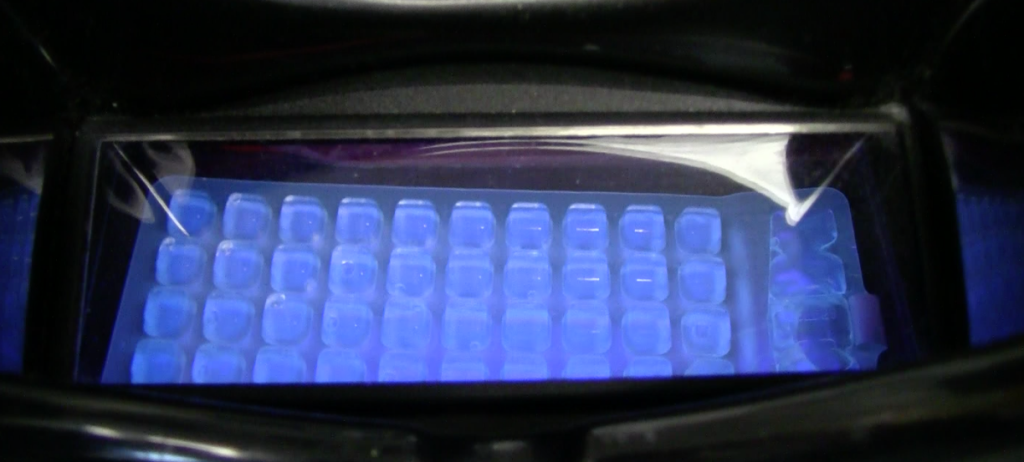

In the laboratory, analysts test for two categories of contaminants: coliform bacteria and minerals.

Coliform bacteria are “indicators” – they generally aren’t harmful, but high concentrations suggest that a bigger problem is hiding in the well.

Runoff containing animal wastes is the main source for coliform contamination in ground water. Livestock from farms are the biggest culprit, especially in “pig parlors” or intensive piggeries, where the waste from hundreds of the animals is directed to one lagoon that can leak or overflow into the groundwater.

People whose water comes from shallow bored wells are more likely to be sickened by bacterial contamination. But owners of drilled wells can be affected, too. If the well’s submerged pump is not thoroughly chlorinated before being lowered back into the ground, bacteria from the grass and soil could be installed along with the pump.

At the UGA testing lab, roughly one-third of the samples brought in by Morgan County householders contained coliform bacteria. Of those samples, about 17 percent tested positive for E. coli, the type of coliform bacteria that poses the greatest risk to human health.

While some strains of E. coli occur naturally in our bodies, other varieties are harmful to humans and can cause diarrhea, vomiting and stomach cramps. Some of these infections can cause kidney failure, which is potentially fatal if not treated. About 265,000 infections and 100 deaths from E. coli are reported each year nationally, though there are many sources of this bacteria other than water.

A mere trace of bacteria is bad news for the owner, Saha said, even if it’s not a potentially fatal strain.

Minerals, the other most likely set of contaminants, are more common and easier to spot. The geology of an area is often a predictor, though not the only one, of what kind of mineral contamination may be found there.

In Morgan County, water hardness, a build-up of calcium and magnesium, is a big issue. It’s common in water samples tested at the county extension office in Madison, according to Lucy Ray, the county agent.

Hard water yields a sticky film when combined with soap, which can wear out clothes and stain dishes. Other minerals – especially iron and manganese, which come from Georgia’s red clay – taste strange and appear as colored splotches in the sink and bathtub. If the mineral stew gets thick enough, it can clog taps and even reduce water pressure, Ray said.

Clear may not mean clean

Contamination isn’t always obvious. The look and taste of the tainted water may seem normal.

Lundy said families that drink from a tainted well daily can build up a tolerance to what’s in the water.

The danger, he said, is when “you have your elderly grandmother come stay with you, or your aunt that’s not used to that water, and they drink it and they get sick.”

Kumnick of Public Health , though, said the possibility of developing a tolerance depends on the dose and on the specific contaminant. Benzene, for example, would carry a significant health risk.

He said his agency and DNR’s Environmental Protection Division are discussing a partnership to ensure that water systems in Georgia have adequate oversight.

Well owners who want to make sure their well water is safe can bring a sample to their local extension service office. Water tests are fairly cheap – $15 for the basic test, $30 for the bacteria test – and highly accurate.

GHN Editor Andy Miller contributed to this article.

Lee Adcock is a first-year health and medical journalism student at the University of Georgia. She is also a music critic for various media outlets.